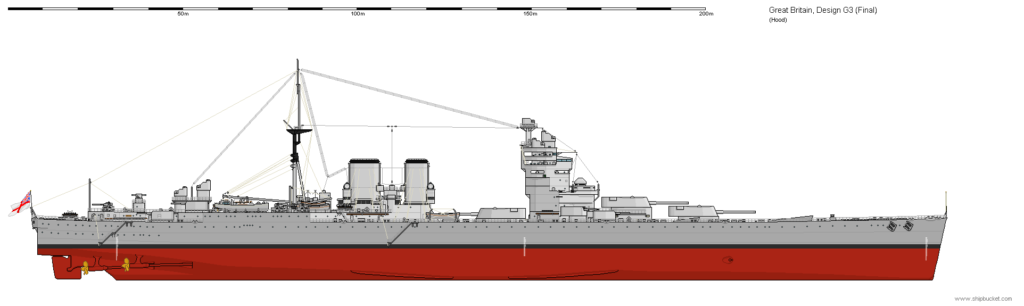

In 1920 the British Admiralty proposed a £75 million capital ship programme, revolving around four battlecruisers and four battleships of unprecedented size and power, embodying all the lessons Britain had learned from the First World War and post-war firing tests.[1] They were Britain’s answer to a naval race brewing between the United States and Japan.

In the end the effort only got as far as the battlecruisers, which after months of Cabinet obstruction were suddenly approved, ordered with relative haste in late 1921, then suspended just days later. They never received formal names.[2] A few months after that, the ships were cancelled altogether, following a diplomatic conference in Washington where agreements included the ‘Five Power Treaty’ (‘Washington Treaty’) on naval limitation.[3] As a result they are usually classed as having been ‘cut down by Washington’, along with the Japanese and American capital ships cancelled by that treaty.[4]

In fact, that wasn’t the full story. The British battlecruisers were certainly listed in Section II as ‘4 ships building or projected’ under the British Empire table in Section II, the schedule of capital ship scrapping and replacement.[5] But, as we shall see, that was simply the last act in the political saga of intrigue and cost-cutting in which it was clear to the Admiralty that the British Cabinet had no serious intention of funding them.

None of this was surprising. By the end of 1918, when the ‘war to end all wars’ finally reached an armistice, Britain was financially exhausted. The Treasury – which held the government’s purse-strings and was responsible for providing Cabinet with advice on fiscal policy – wanted cuts, particularly to the military. In July 1919 the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Austin Chamberlain, urged Cabinet to slash the Royal Navy to just 15 commissioned capital ships, with more cuts to follow in 1920.[6]

No new capital ships were authorised, and the Admiralty had to accept the government expectation that arms-control agreements would be part of the post-war world. When Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Jellicoe asked the Admiralty for details of building programmes in June 1919 he was told they relied on ‘negotiations for limitations of armaments’, and that current construction was ‘confined…to completion of ships in an advanced stage’.[7] This helped frame a mood of constraint, given teeth by the Committee On National Expenditure under Sir Auckland Geddes, which recommended a ‘Ten Year Rule’ that required the military to plan on not having to fight a major war for another decade. The naval estimates for 1920 were cut from 170 to 60 million pounds. Policy was in churn with the demise of the German navy, and no new policy was possible until post-war power balances shook down. For the interim the Admiralty was told to maintain a 60 percent superiority over the next strongest naval power after the United States.[8] This meant Japan, Britain’s ally.

The fact that the US Navy was excluded was significant. In 1916 the United States authorised a naval build-up aimed at parity with the Royal Navy. That was a sticking point in 1919 when British and US delegates met in Paris to discuss a peace treaty with Germany.[9] The decision in London to – in effect – set the issue aside and define another power as target for Britain’s 60-percent superiority target triggered further debate over the relationship with the United States.

All came amidst a general world mood for disarmament. In the United States, although Congress had authorised the US Navy’s major build-up in 1916, there was less appetite to extend it,[10] particularly as the US economy crashed into depression in 1920-21. That brought a 17-percent drop in gross domestic product over 14 months.[11] So it was no surprise when, in early 1921, incoming US President Warren Harding – elected on a platform of fiscal cuts[12] – began talking about an international disarmament conference.

In Britain the Admiralty’s other problem was that while the Royal Navy ended the First World War with an overwhelming number of capital ships, many were obsolescent, and the newer classes did not match the behemoths under development in Tokyo and Washington.[13] That was made worse for the Admiralty as wartime lessons were digested, and as the results of post-war experiments came in.[14]

The only answer was clean-sheet designs, and the Admiralty began looking into the possibilities in earnest from mid-1920.[15] They envisaged four battleships and four battlecruisers over two years – a practical return to pre-war tempos. The battlecruisers were prioritised for the 1921 programme, and the final design combined the latest engineering lessons with an outstanding mix of speed, protection and fire-power.[16] Building them, however, was another matter. Voices for disarmament remained loud, and there was a public outcry as soon as it became known the Admiralty were contemplating a major programme. Various senior officers then waded into the fray.[17]

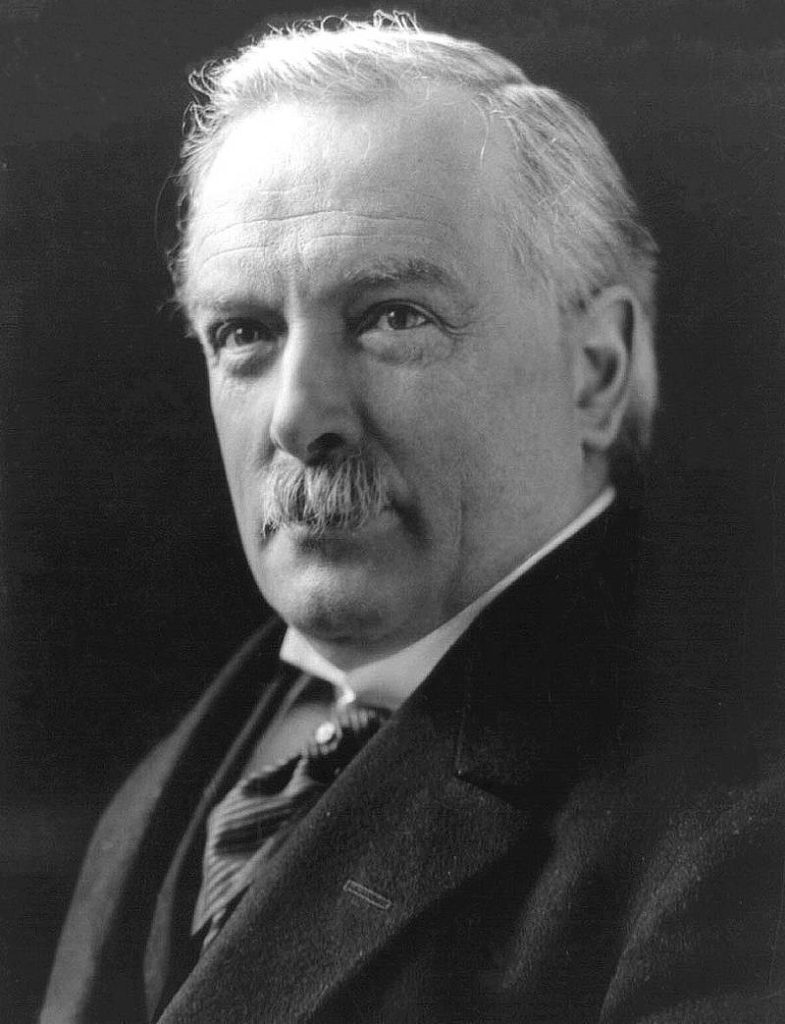

The Admiralty’s stumbling block was the Prime Minister, David Lloyd-George, who favoured military cuts. In December 1920, his Cabinet forbad the Admiralty to build capital ships until wartime lessons and the ‘place and usefulness of the capital ship in future naval operations’ had been investigated by a Committee of Imperial Defence sub-committee.[18] The First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir David Beatty, refused to back down, was supported by Winston Churchill; and the upshot was a further political fracas.[19]

In the end the sub-committee reached no firm conclusions. Lloyd-George prevaricated, and during the first two weeks of March 1921, decided to allow the Admiralty starting funds for four of the eight ships they wanted, although that amounted to only £15 million of the estimated £75 million total cost.[20] It was also conditional on the self-governing Dominions chipping in. The draft naval estimates for 1921-22 were approved, on those terms, 17 March.

This quietened the pro-navy lobby, but when the Admiralty approached the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Austen Chamberlain, for approval to order long-lead items – guns and armour – they were refused. The estimates might have been approved, but Cabinet had not confirmed the spending. Nor did Lloyd-George’s government now wish to consider the matter.[21] By this time the United States was making noises about an arms limitation treaty, and Cabinet anticipated it would be achieved. That took priority out of the Admiralty requests.[22]

The agreement, in short, was purely a sop to the nay-sayers, and when push came to shove, Lloyd-George wasn’t prepared to support it. In a sense that was practical. He was aware of the cost of the pre-war naval race, which had been controversial. The post-war world was poorer, and still shaking down. Issues included the future of the Anglo-Japanese alliance, which was up for renewal, international interests in East Asia – including China – and the rise of US naval power.[23] Lloyd-George’s government ran these past the self-governing Dominions and other representatives of the British Empire at the Imperial Conference due to be held in mid-1921. At the same conference, the Admiralty persuaded Britain’s Dominions to provide 2.2 million pounds between them towards the new ships, siphoned from their share of German war reparations.[24] It was a token, but Beatty clutched at the straw and approached Cabinet on 21 July to request a start on the battlecruisers.

This time Beatty met a more favourable reception, in part because the March arrangement had been on the basis of the Dominions providing something – but also because the ground rules had changed. On 8 July, President Harding invited the major nations to join an international conference to be held in Washington that November.[25] Disarmament was on the table, and Lloyd-George’s government expected to come to an agreement; but with the US and Japanese capital ship programmes forging ahead, they needed a better bargaining counter than an offer to scrap older dreadnoughts already laid up for disposal. The new battlecruisers were it.

To some extent the decision was a bet both ways. If the conference failed, Britain would need to find the money to build new ships. It silenced the pro-Navy lobby, Admiralty voices, and lobbyists from the ship-building industry. However, the risk of the conference failing was low: the world was beset with economic depression and a weariness with war. The Cabinet position was further underscored by ongoing financial decline. In the fourth quarter of 1921, Britain’s GDP shrank by 4.71 percent – a sharp recession – and the public debt-to-GDP ratio was skyrocketing.[26]

Cabinet authorisation still required Parliamentary approval, but that came on 3 August when the general naval estimates were passed. The Washington conference was confirmed a week later on 11 August, and the agenda published six weeks after that. This covered more than naval limitation, but naval issues were closely inter-related with post-war power-balances.[27] Britain’s need to make the battlecruisers diplomatically credible was underscored by the contracts. These went to John Brown, Swan Hunter and Fairfield on 24 October, and William Beardmore & Co on 1 November,[28] this last with less than a fortnight to go before the conference started. However, the orders were suspended, pending the outcome of the multi-national discussions that began on 12 November in the Continental Memorial Hall on Seventeenth Street, Washington.[29]

The fact that the conference had been confirmed months before the contracts were offered underscores the political calculation behind the Cabinet decision to allow the ships to be contracted. As one historian has pointed out, it was cruel to the hopes of the workers and companies involved.[30] It was, however, also pragmatic. Post-war international power-balances and interests needed defining for Britain to deal with its financial and geo-political position, and they needed every available tool. Discussions in Washington produced several treaties, including a Four Power Treaty replacing the Anglo-Japanese alliance, a Nine Power Treaty that pledged independence for China, and a Five Power Treaty on naval disarmament, signed by Britain, the United States, France, Italy, Japan – and Britain’s self-governing Dominions, New Zealand, Australia, Canada and South Africa.[31] The Five Power Treaty on naval disarmament was the one usually known afterwards as the ‘Washington Treaty’, masking the fact that it was but one of several international agreements hammered out at the time.

From Lloyd-George’s perspective the Five Power Treaty resolved the politics of the Admiralty’s building programme. The four battlecruisers were cancelled in February 1922, soon after the treaty was signed.[32] The rest of the programme was dropped. One outcome was that Britain was allowed to build two new capital ships within the treaty limitation. However two such vessels were seen as more affordable to buy and operate than eight larger ships. The Five Power Treaty also removed the potential for an open-ended naval race.

In short, Lloyd-George’s cabinet – when wrestling with Britain’s myriad post-war social, economic and political issues – had got its way at virtually every level when it came to naval matters.

For more on British inter-war capital ship politics, remember to check out my short book Britain’s Last Battleships, now in second edition.

About the author: Matthew Wright is a professional historian who has been extensively published by Penguin Random House, among others, has written many academic papers, and is best known for his international contribution to the study of military and naval history. Many of his books have been used as university texts. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society at University College, London. Visit him online at www.matthewwright.net

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2020

[1] For summary see, e.g. Norman Friedman, The British Battleship 1919-1946, Seaforth, Barnsley, pp. 203-213.

[2] R. A. Burt, British Battleships 1919-1945, Seaforth, Barnsley, 1993, 2012 edition, p. 337. Various potential names have been proposed for the class.

[3] Usually known as the ‘Washington Treaty’, although this is a metonym.

[4] https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000002-0351.pdf accessed 12 January 2020.

[5] Ibid, Section II.

[6] Christopher M. Bell, Churchill and Sea Power, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2013, p. 89.

[7] ADM 116/1831, D of P to Jellicoe, 9 July 1919.

[8] Bell, p. 89.

[9] Norman Friedman ‘How promise turned to disappointment’, Naval History Magazine, Vol. 30, No. 4, August 2016.

[10] Bell, p. 89.

[11] https://mises.org/library/forgotten-depression-1920, accessed 13 January 2020.

[12] Stern, pp. 98-99.

[13] See, e.g. Sturton (ed), pp. 126-128, 175-178.

[14] Friedman, p. 203; see also Burt p. 335.

[15] Ibid, pp. 207-210.

[16] For summary of particulars see, e.g. Ian Sturton (ed), Conway’s All The World’s Battleships, 1906 to the present, Conway Maritime Press, London 1987, p. 91: Burt p. 337.

[17] Barry D. Hunt, Sailor-Scholar: Admiral Sir Herbert Richmond 1871-1946, Wilfred Laurier University Press, Waterloo, 1982, pp. 119-120.

[18] National Archives CAB/23/23, ‘Cabinet 67(20), Conclusions of a meeting of the Cabinet, held at 10 Downing Street, S.W., on Wednesday, 8th December 1920, at 11.30 a.m.’.

[19] Hunt, pp. 122-124.

[20] Robert C. Stern, The Battleship Holiday: the naval treaties and capital ship design, Seaforth, Barnsley 2017, p. 94.

[21] Ibid, p. 96.

[22] See, e.g. Friedman, p. 213.

[23] For discussion see Ira Klein, ‘Whitehall, Washington, and the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1919-1921’, Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 41, No. 4, 1972.

[24] Stern, p. 97.

[25] Ibid, p. 99.

[26] See https://voxeu.org/article/walking-wounded-british-economy-aftermath-world-war-i, accessed 12 January 2020.

[27] ‘Notes on International Affairs’, The American Political Science Review, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 285-297.

[28] Stern, p. 97.

[29] ‘Notes on International Affairs’, The American Political Science Review, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 285-297.

[30] Stern, p. 97.

[31] https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000002-0351.pdf

[32] Sturton (ed), p. 91.

Recent Comments