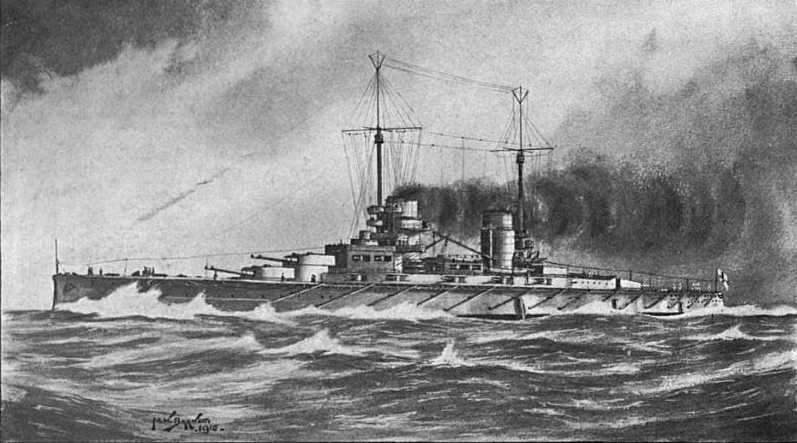

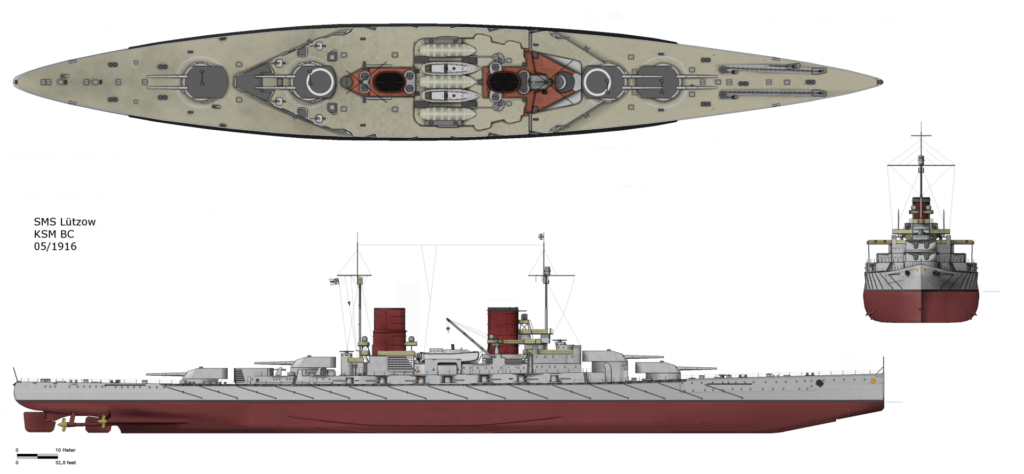

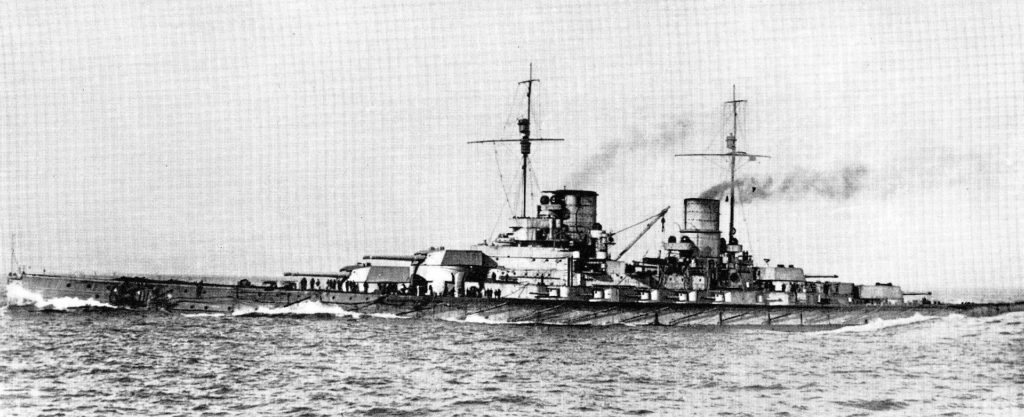

The Battle of Jutland comes down to us through history bearing many tales of ‘daring-do’. Story’s of ships exploding, of sailors manning their posts when all is lost, of wrong decisions and Admirals blinkered to the moment. Of ships being battered and surviving to limp home and of the smaller vessels weaving between their bigger kin, like terriers on a scent. But one legend is of the almost indestructibility of the German Battlecruiser. It will never be agreed who won, but surely we are all in the same mind, that Hipper’s gray hounds showed a stubborn reluctance to die. Two ships symbolize this, the Lutzow and the Seydlitz . Both received over twenty large calibre hits, and while one limped home, the other had to be scuttled as she was beyond saving. This trait was not confined to the Imperial Navy alone, the Warspite showed the same stubbornness with over 13 large calibre hits on her, and arriving home with 150 holes within her structure. But it’s the Lützow that has always fascinated me, for the battering she took, and the crew that fought to save her through the early hours of the 1st June. The contrast between the fighting spirit or moral, within the German crews of May 1916 and November 1918 is almost beyond belief, that last day in May could be seen as the apex of the Imperial Navy’s surface fleets fighting spirit?

The SMS Lützow had steamed and fought, like all the other 250 ships on that long afternoon in May. But by the early evening the 26,741 ton Battlecruiser was a mess. She had received over twenty large calibre shell impacts, and two of those from HMS Invincible had struck below the waterline. Water was flooding into her and of her seventeen internal compartments, five were flooded. But in return Lützow had delivered a shell that had penetrated the Invincible’s ‘Q’ turret and the detonation of the magazine had brought death and destruction to the British Battlecruiser. But to appreciate her loss and the raw courage of her crew, we need to follow the chronological story of the damage inflicted onto her. How she was mauled and brought to the point where the scales tipped and survival was just beyond her.

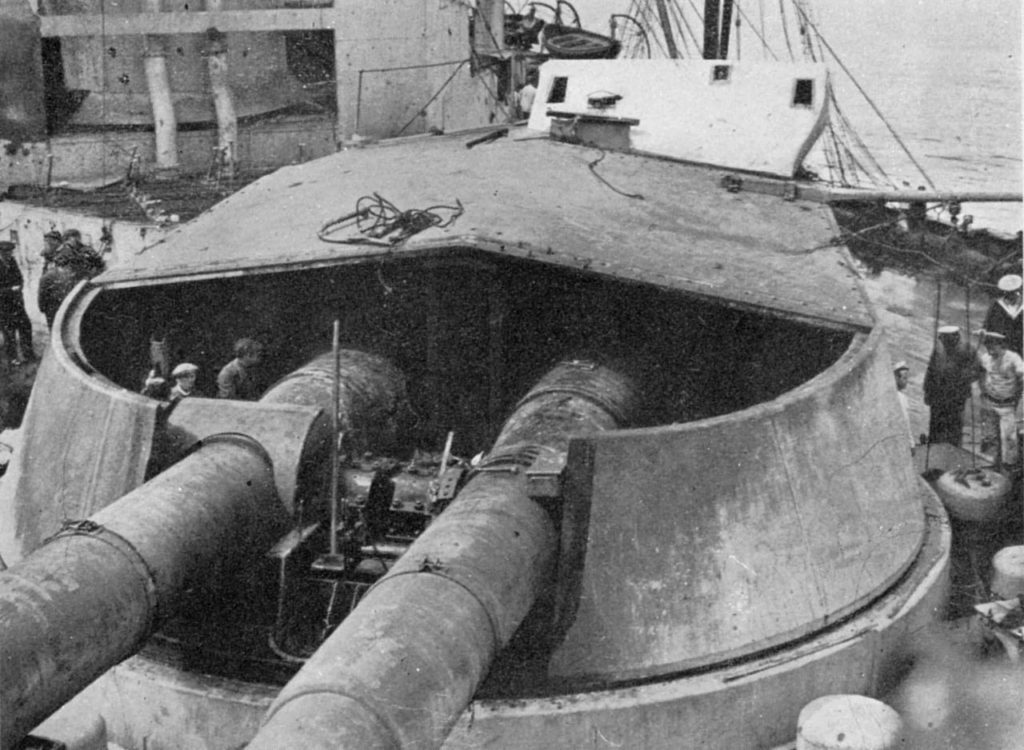

The first shell to strike home on the Lützow was at 17:00 when a 13.5inch shell from the guns of Beatty’s flagship, HMS Lion impacted on the forecastle near the capstans, creating the first large hole on that deck. The force of the explosion shook turret ‘A’, rocking its massive bulk from side to side. The first casualties of the day for the crew were three men of the turret’s crew, who within the working chamber were knocked out by the gasses from the open gun breeches.

The second shell followed in the slip steam of the first, a second 13.5-inch from the Lion. This was to leave a second large wound or hole within the forecastle deck, and it was these two forecastle hits that would later allowed great quantities of water to enter into the ship, when her bow began to drop beneath the surface. The water would flood through the areas above the armoured deck, affecting her stability towards the end.

The next shell, (number three) was of a 13.5-inch fired by the Princess Royal. The 1,400 lb (635.03 kg) shell traveling at 2,491 feet per second (759 m/s) crashed into battle cruiser between ‘A’ and ‘B’ turrets at 17:15, where it penetrated into the hull, and destroyed the forward combat dressing station. The force if its impact left everyone there either dead or wounded. The ship carried four doctors that day and two were to be killed and one wounded. The Princess Royal sent the fourth shell from the same salvo. It struck on the belt armour aft in the proximity of frame 120. The shell failed to penetrate the 12-inch (300mm) of armour, but the impact was massive and was felt throughout the hull.

The fifth shell came 58 minutes later from the 5th Battle Squadrons Barham, and it too struck the belt armour, around frame 210 just below the waterline. The shell shattered on impact with the armour, and while not piercing it, the plate was unseated permitting the two outer wing compartments to fill with water. The six and seventh shells were delivered at 18:25, and both were once more, 15in shells from the Barham. They struck the superstructure between the Lützow’s two funnels and destroyed the both the main and reserve wireless stations. The twelve crewmen who were stationed there were killed by the explosion. The Lützow was the battlecruiser squadrons flagship, and with one explosion Rear-Admiral Hipper was rendered incommunicado with his command. Nor could he communicate with the fleets C-in-C, Sheer. His only method of communication, in a funnel and cordite smoke filled North Sea, was by searchlight. The shell also caused the starboard III 15cm gun to temporarily failed, but it’s crew quickly returned it to operation. Hit number eight was another 15-inch shell from the 5th Battle Squadron, but this time from the Valiant. It struck at 18:30 between the IV and V port 15cm casemates. But the shell failed to penetrate the armoured deck and caused what by the days experiences would count as ‘minimal damage’.HMS Lion following the battle. SMS Lützow scored several hits on her, including one that destroyed the turret.

HMS Lion following the battle. SMS Lützow scored several hits on her, including one that destroyed the turret.

Fifteen minutes later (18:45) the ninth shell, a 13.5-inch from the Princess Royal struck the ships superstructure side to port just below the conning tower, causing once more ‘only minor damage’. Hit ten was at 19:19 from the Lion, and was another of her 13.5-inch shells, which struck the forecastle once more, near the bow. The eleventh impact was from the same salvo, being a second hit from the Lion. This time the shell struck the port casemates roof and penetrated the armour, before passing forward to detonate just behind turret ‘B’. The explosion caused a a fire to start amongst the damage-control material stored in the area, which added to the smoke the Lützow was emitting from her fires.

Shells twelve and thirteen were once more in quick succession when at 19:26 Lützow was struck by two 12-inch shells fired from either the Invincible or Inflexible, both striking below the waterline. One shell struck the broadside torpedo room beneath the armoured belt, and the other struck the lower edge of the 100mm-thick armour and also penetrated the broadside torpedo room. Two more hits, fourteen and fifteen followed on the tail of its predecessors. These were two more 12in shells, once more from the Invincible or Inflexible, and struck penetrating below the bows armour and waterline, destroying the torpedo room located there. These four shells all struck the forecastle beneath the armoured deck and the damage caused allowed huge quantities of water to floor below the armoured deck. The waters put an increasing amount of strain on the bulkhead at frame 249, and the ships speed had to be reduced at first to 15 knots. But the pressure didn’t deminished and speeds of 12 knots and finally just 3 knots followed. Bulkhead number 249 was not by now completely watertight and the sea water penetrated compartment XIII and then XII. Later during the night the water would seep into compartment XI, the forward boiler room, through both the joints of bulkhead 249 and the speaking tubes. The flooding increased the draught forward quickly to 12 meters.

Her sixteenth shell was at 19:27 in the form of a 12-inch projectile once more from either Invincible or Inflexible, and it struck the upper deck of the forecastle, producing another large hole in the deck. The next shell, number seventeen was another 12-inch shell, again from either the Invincible or Inflexible. It struck the belt armour near its lower edge to port at around frame number 165 and below the IV 15cm casemates. The intruder pierced the armour and was found wedged on the Böschung (sloping armour) without detonating. But the pressure of gas caused damage to the IV 15cm gun leaving it unserviceable.

Hit Eighteen followed three minutes later at 19:30 and was a 12inch shell striking in the belt armour above the waterline between the port III and IV casemates, but it shattered on impact, without any detonation. The nineteenth shell was at 19:30, and was also a 12-inch shell, which struck the port side net shelf just below the V 15cm gun and detonated. The next shell, number twenty, was at 20:07 and was a heavy shell which struck the port casemates and put the port combat signal station out of action. The signal personnel were all killed by the detonation and a fire broke out in the compartment.

Hit twenty-one was at 20:15 and was a 13.5-inch shell from either the dreadnoughts Orion or Monarch. It landed on the right barrel of ‘A’ turret and detonated just outside the gun-port. Splinters showered into the turret, the aft hoop was torn off the barrel of the right 30.5cm gun, which was now jammed. The left gun was protected by the splinter shield inside the turret and remained serviceable. Shell number twenty-two was of the same salvo and penetrated the deck between ‘C’ and ‘D’ turrets. The aft dressing station was destroyed and heavy casualties were inflicted on the already wounded and the medical personnel attending them. Of the three doctors, fifteen attendants and 160 to 180 wounded only four personnel remained alive. These four men were hurled by the force of the explosion into the next compartment, where they lay unconscious. The electrical cable to ‘D’ turret, which ran above the armoured deck in this position was also severed, leaving the turret only trainable by hand. But before Lützow was scuttled the electrical personnel had managed to restore the cable connection. Stabswachtmeister Behrens wrote:

“Then a report arrived that a heavy hit had penetrated the aft dressing station from above and exploded there. Obermaat Meyer, wounded, brought this report forward to me. His wound did not appear too bad, and briefly after his report he sat down and began to smoke. In reality he was badly wounded by a splinter and succumbed to this wound 14 days later.

Now it was frighteningly clear to me that all the doctors and specially trained medical personnel were dead or injured. The vision earlier seen: the commander of the ship, surrounded by the four doctors, came before my eyes, and now the present situation; both dressing stations knocked out or destroyed by heavy artillery hits and connected with that the injuries to doctors and specialist medical personnel, and destruction of the greater part of the medicines and medical equipment.

Because there was no alternative the badly wounded were simply taken to a Zwischendeck (steerage) compartment and laid out”.

Hit Twenty-three came at 20:16 in the shape of a projectile once more from either Orion or Monarch, striking to starboard around the area of ‘B’ turret’s barbette, which caused flooding of the starboard I 15cm gun munitions chamber.

The twenty-four shell impacted at 20:17, and was again from Orion or Monarch. It struck the 250mm-thick armour of the starboard side of turret ‘B’, which could still traversed to approximately 280° to port. The aft lower right side wall was pierced, leaving a 13.5-inch sized hole approximately 0.25 sq meters in size. The shell was didn’t penetrate, but it did punched out a large piece of the armour, which was found on the right gun carriage cradle. The loading facilities and right upper hoist were destroyed and men to the rear of the gun were killed. A fore charge located on the right upper powder hoist burned, but a main charge directly above it failed too. The turret Offizier, Kapitänleutnant Fischer, was killed by the gas emissions, but others escaped, although some suffered terribly from burns. The right hydraulic pump in the powder handling room was destroyed.

The last shell, number Twenty-five, was sometime between 20:15 and 20:30. A heavy caliber shell struck the upper main mast above the observation position. The personnel inside the aft conning tower, which was directly beside the tower, heard a deafening impact as the upper mast toppled over.

At 19:50 Kommodore Andreas Michelsen, aboard the cruiser Rostock had ordered the torpedo boats G40, G38, G37 and V45 from ‘I Half-Flotilla’ to assist the heavily mauled Lützow. In addition the G39 came alongside and took on board both Hipper and his staff, transferring him to the Moltke where he could regain control of his squadron. As Hipper departed his stricken flagship, the V45 and G37 began laying a smoke screen between the wounded Lützow and the British line, but before it could be completed, Lützow was struck at 20:15 by shell number, 21, 22, 23 and 24. Lützow herself was to fire her final shell half an hour later at 20:45, from which moment her battle was no longer with the Royal Navy, but for her very continued survival. With that last shell fired, the smoke screen had finally succeeded in hiding her from the British guns. The ship was by this stage heavily ablaze, holed, flooded, and large areas of the interior were filled with the poisonous fumes of the shells, forcing crew members resort to wearing gas masks.

As Scheer attempted to seek the sanctuary of the Jade for the Kaiser fleet, the lone Lützow’s speed had dropped from the 26 knots she had made earlier in the day to 15 knots. By 20:50 the Lützow attempted to pass behind the German line, out of reach of the British guns and using the High Seas fleet as a shield. With her four loyal TB escort standing by her she tried to gain the safety of the disengaged side. As she crawled through the seas, the water continued to enter through her mauled hull and by 21:30, the sea began to wash onto the deck and pour though the shell holes on her forecastle, where they flooded the compartments above the main armored deck, which would quickly bring significant stability problems. At 21:35, with over 1038 tons of sea water on board, an attempt was made to increase her speed, but the water pressure against bulkhead XII and XIII was unrelenting and the attempt was abandoned.

By 22:13 the Lützow and her escort were alone with the last German ship in the line, the Konig, having lost sight of her as she was no longer unable to keep up with the fleet. Scheer’s hope was that in the foggy darkness, Lützow could somehow evade the British and manage to successfully return to a German port. Being unable to keep her place within the Fleet she turned south on her own, and headed for the Jade. By 22:15 she had shipped 2395 tonnes of the North Sea water, but an hour late they had pushed her to 13 knots on a SSW course. But the sea water was unrelenting in its flooding and by midnight it was lapping around the barrels of ‘A’ turret and her draft was increased from her 9.2 meters to 15 meters. This raised questions of, should she even reach Wilhelmshaven, as to how she would slip over the Jade’s sand bars. But one problem at a time….

On deck the bodies of her dead and wounded crew lay amongst the spent shell cases. From the masts fluttered her torn ensigns, twisted signal lines, and pieces of wire from the ruined wireless installation. If it wasn’t for the lookout and the three officers on the commander’s bridge, she would have resembled a ship of the dead. Below on the battery deck, there lay innumerable wounded, but there was no longer any doctor to attend to them or ease their suffering. Screams and cries came from their mouths but no one could help them now.

The 31st turned into the 1st June and she was making seven knots, with a crew still optimistic of reaching port. But as time passed the water pressure on internal bulkheads forced another decrease in the speed to a crawling 3 knots (3.5 mph or 5.6 kph) and her critical forward pumps control rods failed. The ingress of water in the bow only increased faster from this point,(00.50) and this growing body of water added stress to the already struggling bulkheads.

Around 01.00 the flood waters were finally too much for the pumps and the port diesel dynamo could not be kept drained, knocking out her generators, leaving her crew to having to resort to working in candle light in their efforts to save their ship. The twenty-seven men within the dynamo compartment had survived the days horrors, but the chamber was inaccessible due to the flooded adjoining areas. It was to be three-quarters of an hour before they could restore the lighting and only then did the extent of the damage inflicted on their ship became visible.

By now boiler room VI was beginning to flood and although the engines were producing sufficient revolution’s for 7 knots, the sheer weight of the water onboard, and increased draught, resulted in a 5 knot forward progress.

The water had by now flooded into almost every accessible area forward including the forward boiler room, the forward barbette and was in addition lapping up to the conning towers base. Three times members of the crew tried to seal the shell holes that were letting the waters flood in and three times the sinking bow brought waves of water over the repair crew, forcing them back. To try to slow the flooding two attempts were made to sail the ship in reverse but with the bow down 17 meters the screws and rudders were becoming free of the water. An effort by one of her escorts to take her under tow was also to fail in towing the 35,092 (26,741+ 8351) tonnes of warship and water.

At 02:00 an officers conference was called, and the gathered officers were advised the ship now had over 8351 tonnes of sea water inside her, 4209 beneath the armoured deck and 4142 over it. Her four escorts had a total displacement of 4204 tons, which equates to the four of them being stacked onto the Lützow, and then four more added! The forecastle was by this stage 2 meters under water and the large oil boiler room had been abandoned to save the men. The first officer was of the opinion that the ship would finally succumb and sink at 08:00. Her survival was now no longer possible and it was decided to remove the crew onto the escorting torpedo boats. The captain ordered “fires out and abandon ship”, and the wounded were carried by their shipmates to the stern. Then “All hands muster in division order abaft.” was ordered. The survivors made their way quickly and on mass from the lower deck, each one bent on saving his life. It was impossible in the time left to bring up all the wounded, as they were scattered throughout the wreck. Only eighteen men had the good fortune to be carried up, but all the rest who could not walk or crawl had to be left behind.

Six stokers remained trapped within the diesel Dynamo room, where they had lingered to maintain electrical power. They reported through the speaking tubes that the water was slowly rising, but they were trapped as if in a diving bell, compartments all around them flooded. The men trapped within the room had heard the order to abandon ship through the speaking tube. For some it was the final straw in their sanity and they screamed through the tube for help. Two of their number had to be tied up so wild had become their actions and sanity. But in end with no help or rescue possible now, some of those doomed men continued to carry on their work in order to provide the ship with light. They were to go down with their ship. How long their ‘diving bell’ of air lasted we don’t know and can never know. Did they die quickly or did they succumb slowly to the change in pressure as the ship sank to the sea bed? Or did they wait on the sea bed, air remaining to them, but just waiting on the angel of death to release them. A Leutnant zur See wrote:

“I had to think of the six poor stokers that were still alive when the ship sank. They sat in the forward diesel-dynamo switch room, just like a diving bell, and could not get out. They had called me once, as I had a connection with them, and reported that the water was slowly rising in their room. It was held by pumps at a certain height. They maintained their courage and optimism until the last. They were still trapped”.

A report of two British cruisers and five destroyers approaching circulated amongst the living and just at that critical time the fore and middle bulkheads finally gave way. G40, G38, G37 and V45 were ordered, three at a time, to the starboard side as the crew were rescued. The surviving crew members had gathered on the quarter deck and after three cheers for Kaiser and ship they abandoned her, the wounded being removed first. Kapitän Zur See Harder was the last man off. Kapitänleutnant Jung wrote:

“The survivors assembled on the quarterdeck. Above them fluttered the battle flag, shot to pieces by the enemy shells. Where there was no longer any Offiziere, the senior Unteroffizier took command. Still it was a black night. Only in the east the hesitating dawn appeared, heralding the new day. The address of the commander was short and concise. He concluded with the request that we be proud of SMS Lützow and her crew today for their selfless and extraordinary service for the Fatherland. Then three cheers were called for the ship and Kaiser”.

Korvettenkapitän Paschen wrote:

“The disembarking of the crew was exemplary; first all wounded, then quietly, all the remaining. When we cast off as the last boat, I could see in the first of the morning gloom the ship as follows: turret A under water, B an island. The bridge stood in water to the upper deck. The stern was approximately 2m higher than usual”.

G38’s first torpedo was to pass underneath the stern with the decreased draft in the bow raising it up, but her second torpedo struck amidships. As the torpedo struck seven members of the crew were seen running like madmen round the rear deck. Over fatigued, they had it seemed dropped off to sleep and been awakened by the torpedo detonation.

The ship rolled to starboard and capsized at 02:47 and sank, after just 73 days of full commission, in just 2 minutes just as the first rays of the new days sun appeared on the horizon. During her battle, Lützow had fired an estimated 380 of her 720 30.5cm shells and 400 of her 1920 shells for her 15cm secondary guns, as well as two torpedoes. But more importantly she had suffered 115 men killed and another 50 wounded from her crew of 44 officers and 1,068 men.

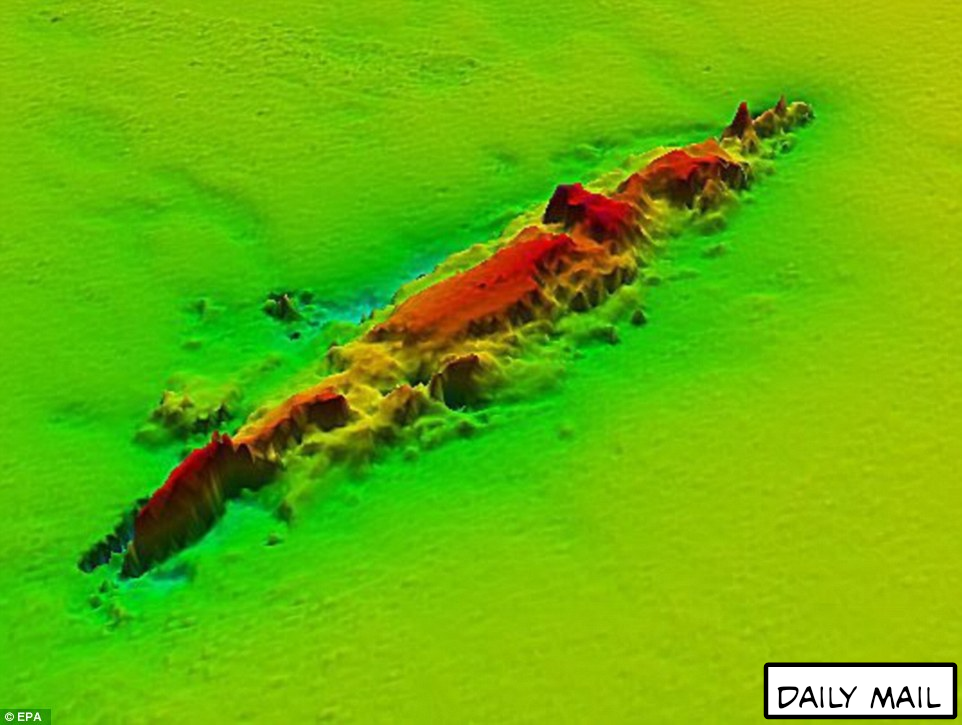

A sonar image of the wreck of SMS Lützow. Photo taken from dailymail.com.

In 2015, the Royal Navy’s survey ship HMS Echo undertook a survey of the area while laying a tide gauge. During the work, Echo’s sonar located Lützow on the sea floor laying eight miles from her last recorded position. Echo took sonar images of the wreck, which her commander stated would “ensure the ship’s final resting place is properly recognized as a war grave.”

Want to Read More Articles by Andy South?

The Race to the Big Gun Battleship

You can also follow him at his Facebook Group The Great War at Sea. Be sure to also follow new articles from Navy General Board on their Facebook page.

Recent Comments