If you were to be asked what was large, metallic, mechanical and steam powered I would imagine your most likely answer would be that of a steam engine or train. But bizarrely in the late 18th century the “Old Man of Europe” the Ottoman Empire commissioned the British built steam powered submarine Abdül Hamid. The Abdül was to be the first submersible to successfully fire a torpedo from beneath the waves when in 1888 she successfully sank an old target ship with a single issue. The Abdül’s sister ship was to sink whilst on route to Czarist Russia where she was to have joined the Imperial Russian Navy.

By 1900 the Abdül Hamid was no longer deemed battle fit and the quest for a steam powered submarine passed first to the Admirals in Paris, before being taken up a few years later by the Royal Navy. During the First World War a number of Admirals in Berlin, London and Paris all saw the potential for a submarine that could maintain sufficient speed to work with the Battle fleet. The speed such a boat would need could only be provided by the use of steam. Given that a steam engine requires copious amounts of air and produces excessive quantities of heat, it was a concept that was only ever realistically to sail the submarine up a proverbial dead end creek. Only in the development of nuclear power was steam to find a home on the submersible, but those early 20th century attempts were doomed from the first hiss of steam in their boilers.

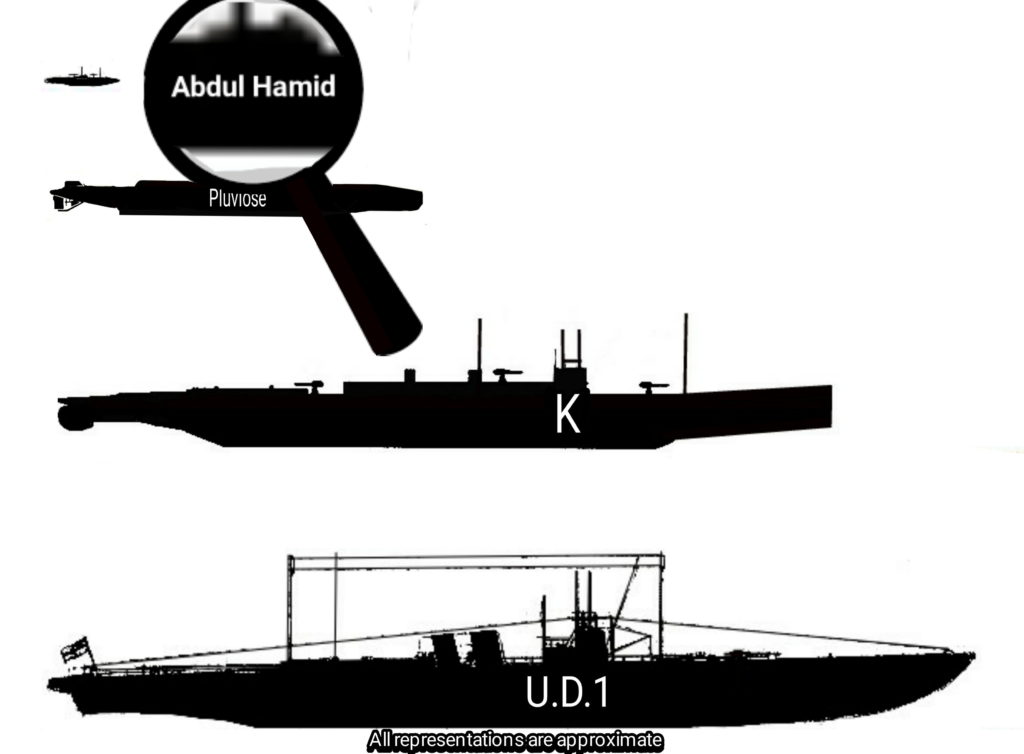

There were (as far as I have to date discovered), only seven serious attempts to produce the steam submarine. The Ottoman had tried first with the Abdül Hamid, the Royal Navy tried twice, first with the Swordfish and then with the infamous ‘K’ class. The French produced three designs, Archimède, Charles Brun and the Pluviôse classes, while the Germans ordered the mysterious ‘UD.1’. Mysterious in that the one hull ordered in 1918 and with some of the materials required gathered, she was never to see her keel laid down before the Armistice came. Then in post war Germany, (in 1946), the file relating to the design was lost in the chaos that gripped the country in those troubled times. The result is that any data we have on the UD.1 is sketchy which will enforce a limit to the following comparisons. But we can at least try with what we do have.

The Archimède, Charles Brun and the Swordfish will be placed aside for this article to simplify matters, plus they were single boat classes or experimental designs. The Royal Navy will be represented by the ‘K’ class, the infamous “kalamity”, “Killer” or “Suicide” boats, while the French Pluviôse will represent the Gallic entry in this European Steam-Vision contest.

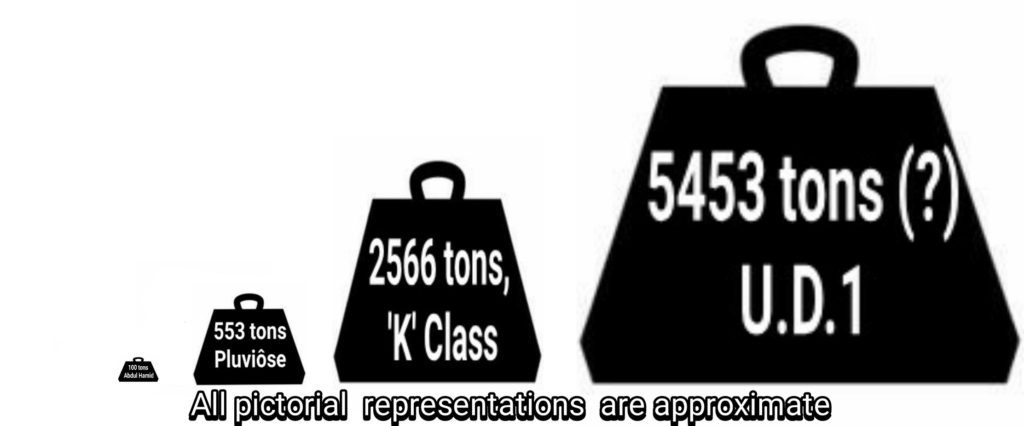

First their displacements. The French Pluviôse was the minnow, with a surface weight of 404 tons, increasing to 553 with her ballast tanks flooded and dived. The Royal Navy’s ‘K’ class weighed in at 1,980 tons surfaced and dived 2,566 tons. The Germanic UD.1 was a projected mammoth of 3,629 tons when surfaced. The giant Germanic mercantile Submarine Deutschland was 1,512 tons surfaced and 2,272 tons when submerged. This equates to a weight increase of water into her tanks of 50.26%. If we transfer that percentage to the UD.1, we arrive at a purely speculative submerged displacement of 5,453 tons.

With their dimensions the Pluviôse had a length of 167.97 feet (51.2 meters), a beam, (or width), of 16.27 feet (4.96 meters) and a draught of 10.33 feet (3.15 meters). This gives the French boat a volume equating to 799.94 meters3. The ‘K’ boats were 337.92 feet (103 meters) long, 26.50 feet (8.08 meters) in the beam, 20.93 feet (6.38 meters) draught and a volume of 5309.69 meters3. The elephantine UD.1 was to have been 410.10 feet (125 meters) long, 34.44 feet (10.5 meters)wide and 21.16 feet (6.45 meters) in the draught, giving her hull a volume of 8465.6 meters3. The UD.1 had a weight of 29.03 meters per meter of length, (including an unclarified quantity of armour) and the ‘K’ boats 19.22 meters per meter of length. For fairness sake, the Pluviôse were 4.90 tons per meter length. Ton for ton and meter for meter, the UD.1 was far heavier than her Entente Cordiale neighbours boat, being 34.48% heavier than her nearest competitor, the ‘K’ boats. For their extra 34.48%, did the Germans get ‘more’ boat in performance and offensive capability?

In the design of the Pluviôse, they were double hull, carried a dual propulsion systems and had the usual electric motors for underwater propulsion. But only a few of the classes earlier boats were steam propelled, the remainder reverting to diesels for surface propulsion. The boat christened as the Monge of the Pluviôse class, is listed as having two Triple-expansion steam engines steam turbines, (700 PS (510 kW; 690 bhp)).

In addition she had Du Temple boiler. These were water-tube boilers that were patented in 1876. The inventor of the design was Félix du Temple (a Frenchman) and they were tested in a Royal Navy torpedo gunboat. A series of water tubes were arranged in four rows to each bank and were S-shaped with sharp right angle bends. This complex design packed a large area of tube heating into a small volume, but in turn made tube cleaning impractical. The drums were cylindrical, with perpendicular tube entry and external downcomers between them. The boats had two of these. The class also had two electric motors for underwater propulsion. (400 PS (290 kW; 390 bhp)). The two shafts gave a surface speed of 12 knots and 8 knots while dived. The range of the boat was 1,000 nautical miles surfaced at 8.5 knots and 27 nautical miles at 5 knots.

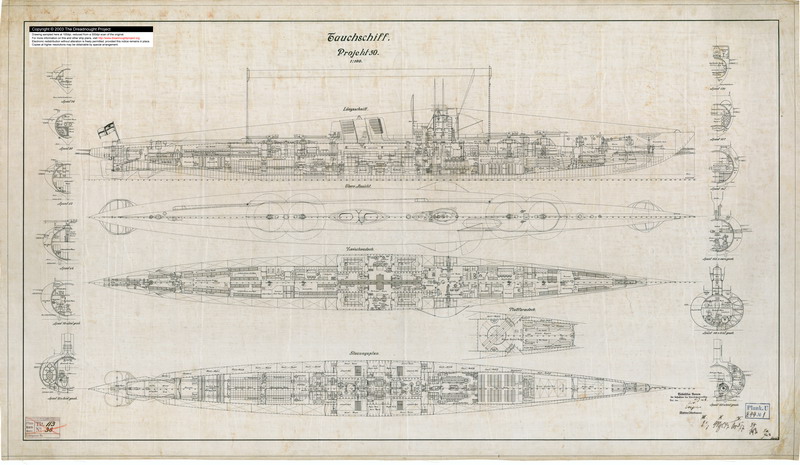

The UD.1 specifications are vague one hundred years on, but the surviving records notes they were to have four turbine or steam engines (2,400 ps/shp). The boilers numbered four from the Wolke company and for submerged propulsion they were to have had two 3,800 shp electric motors. The 415 tons of oil fuel and two shafts were designed to give a surface speed of 23 to 25 knots and 9.5 when dived. The craft are described as “long range” but as to what that range could be we are sadly in the dark.

The infamous ‘K’ boats had in the majority Parsons geared steam turbines powered by twin 10,500 shp (7,800 kW) oil-fired Yarrow boilers. For underwater propulsion the class had four 1,440 hp (1,070 kW) electric motors and one 800 hp (600 kW) Vickers diesel generator for charging the batteries on surfacing. The diesel also provided a reserve method of surface propulsion in the event of the main propulsion being inoperable, a feature insisted on by Admiral ‘Jackie’ Fisher and something the crews were to give thanks for on several occasions. The two propellers provided a surface speed of 24 knots and 8 knots dived. The surface range at 24 knots was 800 nautical miles and at 10 knots 12,500 nautical miles. Submerged at 8 knots this became 8 nautical miles. With the UD.1’s ” long range” label a mystery all we can say for certain is:

| (*=theoretical) | Surface rate of knots | Submerged rate of knots |

| Brumaire | 12 | 8 |

| K class | 24 | 8 |

| UD.1 | 23-25 * | 9.5* |

We have no diving depth for the French boat, but the UD.1 could in theory dive to 328 feet (100 meters) while the ‘K’ boats had a maximum dive depth (on paper) of 200 feet (61 meters). The Kaiser’s boats held the advantage here. The ‘K’ boats were to suffer badly through their lack of height enabling the sea washing down their short funnels and forcing the crew to work in the sauna like boiler room wearing waterproofs. However the UD.1s funnels are at least twice the height of the boats deck guns, making them at least twice the height of the K boats funnels. It seems that flooded funnels would not have been an issue that would not have inflicted the German boats.

But the purpose for all three navy’s steam submarines was the offensive capacity their armaments afforded them. The prime weapon with a submarine was in that period, the torpedo, supported in a secondary role by deck guns. The ‘K’ boats carried depth charges in post commission refits, but aside from looking odd, they are very much an unknown factor, both in performance and usefulness.

The UD.1 was to have been armed with eight 50/53cm torpedo tubes, with one reload for each tube. To muddy the issue even further there are reports that the eight were in fact only six, (or ten) so once again the UD.1 is subject to a question mark. The plans however indicate the UD.1 carried one pair in the bow, two pairs of stern tubes and a set of twin two tubes in a position below the waterline, forward of the conning tower and on the beam. These could be swiveled to fire on either beam, through a set of torpedo hatches. The ‘K’ class were to have had 21 inch or 53.34 cm tubes, but due to unavailability they were built with the 18 inch (45.72 cm) version installed. The British boats had 4 tubes facing forward, with an additional two pairs deck mounted behind the conning tower. But these proved to be exposed to the seas and were to be fairly quickly removed, being replaced by the depth charges.

The first six of the French boat class had a lone 45 cm tube in the bow, but this was complemented by one twin 45 cm drop collar. The Drzewiecki drop collar was a hull mounted external torpedo launching system used by the French and Imperial Russian Navies during the first two decades of the 20th century. Its designer was the Polish engineer and inventor, Stefan Drzewiecki.

The drop collar comprised of a metal framework that encompassed the torpedo allowing it to be rotated to a position which cleared it of the hull, in preparation for firing. The complex system allowed for an arm to move the drop collar in preparation and to the desired angle for firing. The twin system on the aft deck of the Pluviôse class could be rotated from 20° to 170° from the centerline on each side of the ship. Two of the collars faced forward and another two aft.

The French boats appear to not have mounted any gun, but the UD.1 was conceived with three 150 mm (5.9-inch) guns and two 88 mm (3.4-inch) AA guns. But the U-Boat Inspectorate insisted the armament be amended to four 150 mm (5.9 inch) weapons. Two were carried before the conning tower and the second pair aft of the tower. Both pairs were mounted breech to breech. This resulted in one from each pair facing the conning tower, while the remaining pair fired over the respective bow or stern.

The British boat mounted on average (there was a fluctuation between boats through their commissions) two 4 inch and a lone 3 inch serving in an anti aircraft role.

The crew level for the UD.1 was large at 125, while the ‘K’ boat had a crew of 59 and the French boat 25.

We know the French and British boats had major problems with their completed craft. In addition to the feasibility of steam propulsion in a submarine hull, the ‘K’ boats suffered from a poor bow design, living conditions and handling. It’s unknown if Germanic ingenuity would have overcome the problems the British and the French crews encountered. But at the conclusion all we can really say is the German boats were far bigger, heavier armed and faster. Given their size its conceivable their turning circle would (like their British) cousins have resembled that of a battle cruiser.

The British Admirals had conceived their steam powered submarines to serve with the battle fleet in the role of fleet submarines. We know the German boats were heavily armed but we are left to speculate as to the role envisaged for them. Most accounts reference them as ‘cruisers’, which again given their deck armament is not unwarranted. But were they to be fleet or commerce tasked?

The ‘K’ boats were a disaster for the Royal Navy and equate to one of the most fascinating tales for a warship class that never saw a successful action. They were at the ‘battle’ of May Island in 1918 and suffered disproportionate losses for an ‘engagement’ that was devoid of any enemy craft. They were to farrow a number of trenches in the North Seas bed when diving uncontrolled an indecent number of times, with the K13 inflicting a heavy loss of life within her own crew. On one occasion putting the life of ‘Bertie’ the Duke of York and Queen Elizabeth II’s father at risk as the K13 plummeted to the bottom of a Scottish loch. Over the past six months I have explored the National Archives in London, reading in the process 2000 pages of former ‘Top Secret’ files. I have also worked with the Royal Archives in Windsor as well as consulted with Barrie Downer, a former submariner and now the power behind the Barrow Submarine Association. The result is a new book on the ‘K’ class entitled ‘The Suicide Club’ which rewrites the classes history. A number of popular held ‘K’ boat histories are overturned and the question as to the cause of the K5’s loss in 1921 finally answered. The illustrated volume details the classes beginnings, the technical aspects and their service history. It tells the story in unparalleled depth of the Admirals folly…

Recent Comments