When the First World War broke out in August 1914, the British Admiralty had plans to field ground forces, largely to seize coastal areas, if required, for naval bases. Historically there was nothing unusual about sailors fighting ashore. What was unusual was the scale of this intended force: a full brigade. But that was too small for the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, who lobbied to form two further brigades, creating an entire naval division.[1] And his calls were heeded. The British army, though a professional and superbly well trained force, was tiny by comparison with the vast conscript armies massing in Germany. Britain needed all the ground forces it could get.

In theory the new Royal Naval Division (RND) was administered by a standing Admiralty committee chaired by Churchill,[2] but in practise he viewed it as his to personally direct. This was despite the fact that he was a member of Cabinet and, as a politician, not meant to poke his nose into operational matters.[3]

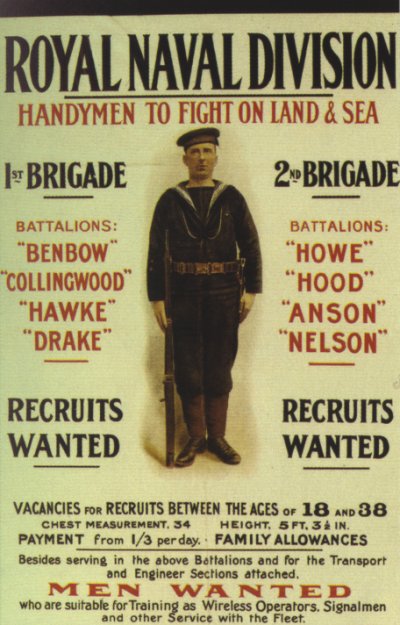

Despite its ground role, the RND was largely a naval force, run on naval lines – including marking time by ‘bells’ – and with senior naval officers featuring in its higher ranks. Much of the force was made up by drawing on a pool of stokers and naval reservists, supported by volunteers and by officers drawn from the army. The battalions within it were named after historic Admirals, including Sir Samuel Hood. At the time, Hood had already been commemorated in a battleship completed in the early 1890s. She was out of service by 1914 – and, in fact, shortly scuttled as a blockship. But even as the old battleship faded from the scene, the 7th (RN) Battalion, part of the RND’s 2 Brigade, was given Hood’s name.

The Hood Battalion was initially led by a regular army officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Arnold Quilter, and included a young New Zealand Territorial officer, Bernard Freyberg, who was commissioned as a Lieutenant Commander in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. A former national swimming champion in New Zealand, Freyberg had been in Mexico – allegedly serving as a mercenary under the rebel leader Pancho Villa – when the First World War broke out. The word is ‘allegedly’: the story of his adventures there later ‘grew in the telling’ at the hands of others, to the point where Freyberg ended up getting an unauthorised biography censored and leaning on officials to constrain his official story. He refused point blank to talk about his Mexican adventure at all. But, whatever he was doing in Mexico in mid-1914, he shortly hastened to London, found he could not get a commission in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, and was then urged to apply for the Royal Naval Division.[4]

Legend has it that Freyberg gained the position by kerb-crawling Churchill. This is not quite true. In fact, Freyberg approached Major George Richardson, a New Zealand officer representing the Dominion on the Imperial General Staff.[5] Churchill had asked Richardson to help recruit for the RND. They were desperately short of junior officers, and Freyberg was exactly who Richardson wanted. Before deciding to jump into the landward arm of the navy, though, Freyberg decided to first introduce himself to Churchill. He managed that by accosting the First Lord in Horse Guards Parade, while Churchill was on his way from the Admiralty to Downing Street.[6]

To formally serve with the Hood, Freyberg had to accept a commission in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. He arrived for duty in a uniform made to navy pattern, using the dun-coloured cloth of the battle-dress adopted by the British Army from 1902.16

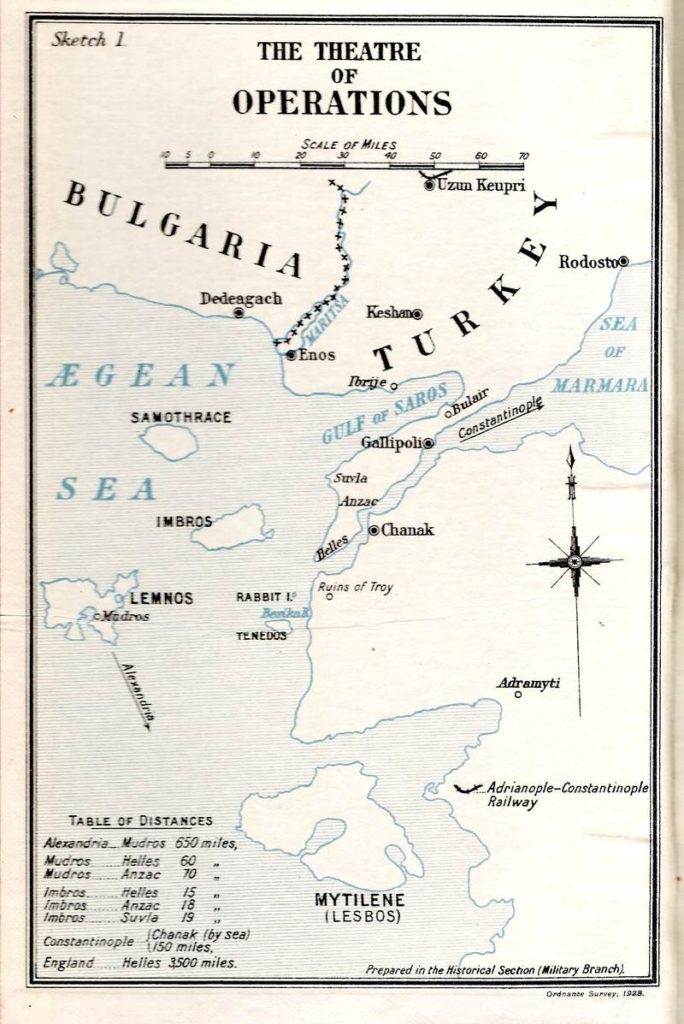

The division fought initially in the defence of Antwerp, where Freyberg was wounded. It was a military disaster. However, Freyberg’s first moment to really shine came off Gallipoli in April 1915, when the RND were tipped to feint a landing from the Gulf of Saros towards Bulair (Bolayir), near the north end of the peninsula, drawing attention from the actual invasion further south. Ottoman forces were known to be entrenched here, the narrowest point of the peninsula and an obvious target. The eleven transports arrived off the beach with their escorts – including the old battleship Canopus – in an intentional display of force, which the warships supported by intermittently bombarding the shore. The transports launched cutters filled with men, all in broad daylight and clear view.

To nail home the deception, the plan called for a platoon-strength landing at night, lighting flares and creating the impression of pathfinding for an assault next morning. Quilter called for volunteers. Freyberg, however, thought just one or two men could do the job, suggesting he and another Hood officer, his friend Arthur ‘Oc’ Asquith, should go.[7] Quilter refused to be the officer responsible for killing the Prime Minister’s son. So Freyberg went alone. It is not clear how far Freyberg engineered the moment, but he let his ambition slip that afternoon, as another naval bombardment crashed out over Bulair. Freyberg watched the excitement, turned to his batman, Petty Officer Robin Tobin, and remarked ‘Do you know, Tobin, I’d give my right arm to win the Victoria Cross’.[8]

What followed became legend, an adventure in the style of Boys’ Own magazine, so impressive that Peter Pan creator James Barrie used Freyberg’s deed as inspiration for his own 1922 lecture on courage.[9] Much of what followed off Gallipoli rested on the fact that Freyberg was a champion swimmer; he stood 6’2” and weighed over 100 kg, most of it muscle. Stories of his strength include the time he carried a piano, solo, up a flight of steps. Later in the war, as a Brigadier-General, Freyberg picked up a wounded soldier and carried him a considerable distance to safety, despite Freyberg’s own exhaustion.

Around 9.00 pm on 25 April 1915, a small cutter – initially towed by the steam pinnace from HMS Dartmouth – closed the shore, under command of Edward Nelson, a former member of Robert Falcon Scott’s ill-fated Antarctic expedition. There was no moon. Soon after midnight on the 26th, Freyberg – stripped down and greased in oil against the chill – slipped into the water and began swimming for shore, towing a waterproof bag carrying what he needed for the diversion. It took Freyberg over an hour to reach the beach in what he described as ‘bitterly cold’ water.[10]

Once ashore he lit his first flare, plunged into the sea to swim along the shore, lit a second 300 metres distant; and then – as he wrote later – crawled inland to find that trenches seen from the ships were dummies. Cold and cramp prevented him pushing too far, so he returned to the beach and lit a third flare.[11] He waited, but there was no sign of defenders, so he took to the sea once more in the hope of finding his friends in the darkness, guided only by a compass bearing. It took some time, and he began to cramp with the cold. Finally, around 3.00 am, he found the cutter and was pulled aboard, mildly hypothermic.[12]

Later, Freyberg’s solo night swim was amplified by mythology into a heroic duck-and-dash before enemy fire.[13] In reality, as he noted in his one-page hand-written report on lined foolscap – ‘the shore was not occupied’.[14] But the risks were clear. While there was doubt as to whether the Ottoman forces in the area had been fooled by the RND’s feint,[15] there was no denying Freyberg’s courage. Aside from death or capture ashore, he had faced a high chance of not being able to find the boat in darkness as he came back.

A little while later, Freyberg learned he had been awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his action that night – a decoration one notch below the Victoria Cross. It was the first of four DSO’s he eventually won during his long career. In the immediate, though, Freyberg went on to serve with the Hood Battalion ashore in Gallipoli, where he was wounded several times. He eventually became commander of the Hood Battalion and – as part of 63 (RN) Division – led them in their major battle of the Somme campaign in 1916, during which he was seriously wounded – and won that VC.[16]

For more on this incredible man and his outstanding life – including Freyberg’s ongoing connection with the Royal Navy through friends such as Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, former First Lord Reginald McKenna, Admiral Sir Andrew Browne Cunningham, and Churchill – check out my book Freyberg: A Life’s Journey. Click to buy.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2020

[1] Douglas Jerrold, The Royal Naval Division, Hutchinson & Co, London, 1923, p. 2.

[2] Ibid, p. 4.

[3] See, e.g. https://www.naval-history.net/WW1NavyBritishAdmiraltyPart01.htm#1, accessed 29 September 2020.

[4] Matthew Wright, Freyberg: A Life’s Journey, Oratia, Auckland 2020, pp. 36-40.

[5] Noted in Peter Singleton-Gates, General Lord Freyberg, VC, Michael Joseph, London 1963, pp. 27-28.

[6] Singleton-Gates, p.28; but see also Paul Freyberg, Bernard Freyberg, VC: Soldier of Two Nations, Hodder & Stoughton, London 1991, p. 37.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Cited in Singleton-Gates, p. 49.

[9] Paul Freyberg, p. 51.

[10] Quoted in Paul Freyberg, p. 56.

[11] Singleton-Gates, p. 50.

[12] Paul Freyberg, p. 56.

[13] For example, Jerrold, p. 80.

[14] Singleton-Gates, p. 51.

[15] Geoffrey Sparrow and James Ness MacBean Ross, On four fronts with the Royal Naval Division, Hodder & Stoughton, London 1918, p. 46.

[16] Matthew Wright, Freyberg’s War, Penguin, Auckland 2005, pp. 19-21.

Recent Comments