In March 1909 there was a good deal of around Australia’s major cities about responding to the latest Imperial naval crisis by giving Britain a battleship. At a time when social militarism was a major feature of society the call resonated. It also came on the eve of a significant Commonwealth government conference to discuss defence matters, in which the long-held idea of Australia getting its own naval forces for local waters was top of the agenda. This local fleet was very different from a battleship offer and widely expected to become formal policy despite Admiralty opposition to the concept.

That combination of both a possible ship gift to bolster the Royal Navy, and an independent force protecting Australia’s waters set alarm bells ringing across the Tasman in New Zealand. A local Australian fleet – despite being couched as a local defence within the wider umbrella of Imperial naval power run from London – would eliminate the Royal Navy’s Australasian Squadron that had provided a direct naval presence in New Zealand waters for decades. New Zealand would either have to follow the Australian lead, or lose out. This stood against the policy of New Zealand’s Liberal government, which was leaning towards a federal approach to naval defence, in which each of Britain’s children purchased ships – something that the Australians now seemed likely to do, albeit as a one-off for different reasons. But that still meant they would gain the moral high ground such a gesture would create with the public in this age of social militarism and flag-waving patriotism towards Empire.

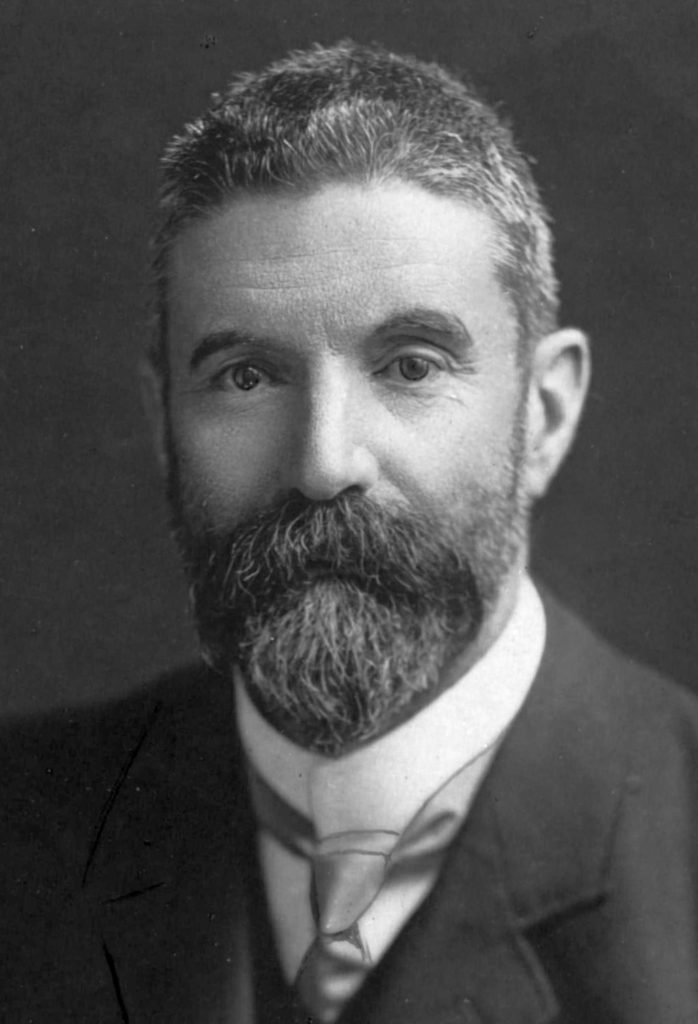

The result was that the Prime Minister, Joseph Ward, decided urgent action was necessary and wrote a Cabinet paper proposing a New Zealand gift, which Cabinet approved on 22 March. Their approval enabled Ward to make an offer the same day, undermining the Australian fleet proposals and – at the same time – stealing the moral effect of making a patriotic gesture to the mother country. The result in Australia was electric, redoubling public demands to do the same. Formal fund-raising began in Sydney, and two of the state governments declared that if the federal government did not offer a dreadnought, they would. Andrew Fisher’s government dragged the chain: they already had a political battle ahead with the Admiralty over their local fleet and had no intention of paying for gift warships atop the local fleet expense. Public opinion differed. In the end it became an election issue, and the incoming ‘fusion’ government of Alfred Deakin offered an Australian gift dreadnought on 4 June, separate from the fleet which remained the core of Australian naval policy.

That satisfied pro-Imperial voices. Like Ward across the Tasman, Deakin did not consult his own Parliament before making the offer – a point that also got him into hot water, although a motion of censure failed.[1] But unlike the New Zealand offer, the Australian offer was qualified. The cablegram to the British government read, in part, ‘They also beg to offer to the Empire an Australian Dreadnought, or such addition to its naval strength as may be determined after consultation’ (my italics). The dreadnought gift was debated in the Senate on 8 July, when the cost atop that of the expected local fleet became a significant issue,[2] due to a political argument over whether to raise loans for the proposed local navy. A Naval Loan Act was already before the House in draft (‘Bill’) form, but had not been passed – and was directly opposed by Andrew Fisher, now leader of the Opposition.[3]

Where next depended on the Admiralty. The two dreadnought gifts were an embarassment to the British. While ostensibly supporting the Empire in an hour of apparent danger – the moment when German dreadnought construction was thought to have accelerated – the offers also reflected the interplays of trans-Tasman politics. And they interfered with the Admiralty’s intent to maintain control of its own procurement. The more crucial issue was the Australian demand for a local fleet to defend its own waters, which stood against Admiralty policy of central control, and which the Sea Lords had long opposed. By 1909 this attitude to Australia’s demands had put the Admiralty at odds with the Colonial Office, which saw the issue as one of interference with Australia’s right to self-govern.

The answer was a special Imperial Conference called in mid-1909 to discuss the ship offers and resolve Imperial defence issues generally. What the British intended for Australia was privately laid out to the Australian delegates during a meeting at the Admiralty on 10 August 1909.[4] Here the First Lord of the Admiralty, Reginald McKenna, made clear Britain was not ungrateful. His opening statement was unequivocal: ‘the Government of the Commonwealth had offered to present the Imperial Government a vessel of the “Dreadnought” type and His Majesty’s Government had gratefully accepted this generous offer’.[5] However, the Admiralty did not intend it to serve in British waters. Instead, the ship was going to form the centre-piece of a cruiser-based ‘fleet unit’, one of two the Admiralty intended for Australasian and South East Asian waters. This also meant the gift would not be a dreadnought, but a battlecruiser – a type that in 1909 was still known as an ‘armoured cruiser’ or ‘dreadnought armoured cruiser’.[6]

The idea was a piece of political finesse by the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Fisher, who believed fast warships were the way ahead, but had never been able to persuade either the Board of Admiralty or Cabinet to authorise what he wanted. His efforts to have fast battleships adopted in 1905-06 and again in 1906-07 – this time in addition to his ‘dreadnought armoured cruisers’ – had fallen foul of budgetary constraints. Nor could he get armoured cruisers approved in any number. As supernumaries the two gift ships were easier to commute, and Fisher seized upon the opportunity, wrapping them around his new ’fleet unit’ concept. These were small cruiser and submarine forces, led by a battlecruiser. There is some evidence his thinking was evolving as he went. Part-way through the conference Fisher hit upon the idea of these units combining to become a new Pacific fleet in wartime, funded by the Dominions. This became a compromise device for simultaneously resolving New Zealand’s desire to gift ships with the issue of Australia’s demand for its own navy: the infant RAN was defined as a ‘fleet unit’, fulfilling the Australian need for locally-controlled defence while at the same time creating a force that could integrate directly with the Royal Navy in wartime.

The idea of the gift ship being returned to Australia, however, met resistance from the delegation because the cost of running a battlecruiser had not been included in estimates for the cost of a local fleet which, until then, had been conceived as a light ship force. However, the First Sea Lord was able to persuade the Australian delegation, led by Colonel Justin Foxton,[7] to accept the idea. Deakin’s government agreed. And so the Royal Australian Navy came into being, initially as a local force within the umbrella control of the Royal Navy, and centred around a battlecruiser. It was a somewhat larger force than had originally been planned, and paying for it remained an issue. The political debate reached the point later in 1909 where the federal government had to deny that £100,000 included in an £883,699 Supply Bill was intended as a stealth payment for the ship. In fact the bill was intended to fund old-age pensions and, among other things, pay for a sewage system for Parliament House.[8]

The driver behind this issue was the determination of Opposition leader Andrew Fisher that Australia should pay for local defence in peacetime – now including a battlecruiser – out of cash flows, not debt.[9] In the end a proposed Naval Loan Act with £3.5 million borrowing for an Australian navy was defeated. Andrew Fisher became Prime Minister again in 1910 and remained determined to pay for the new navy out of cash flows. The addition of a battlecruiser atop the expected figures was resolved largely by public subscription – a fund-raising drive so successful that in 1911 a £43,000 excess was given to the government, which put it towards the Royal Naval Australian College at Jervis Bay.[10] Other money, collected specifically by the Mayor of Sydney for a possible dreadnought was gifted to a ‘Dreadnought Trust’ designed to bring out child migrants from Britain for rural work.[11]

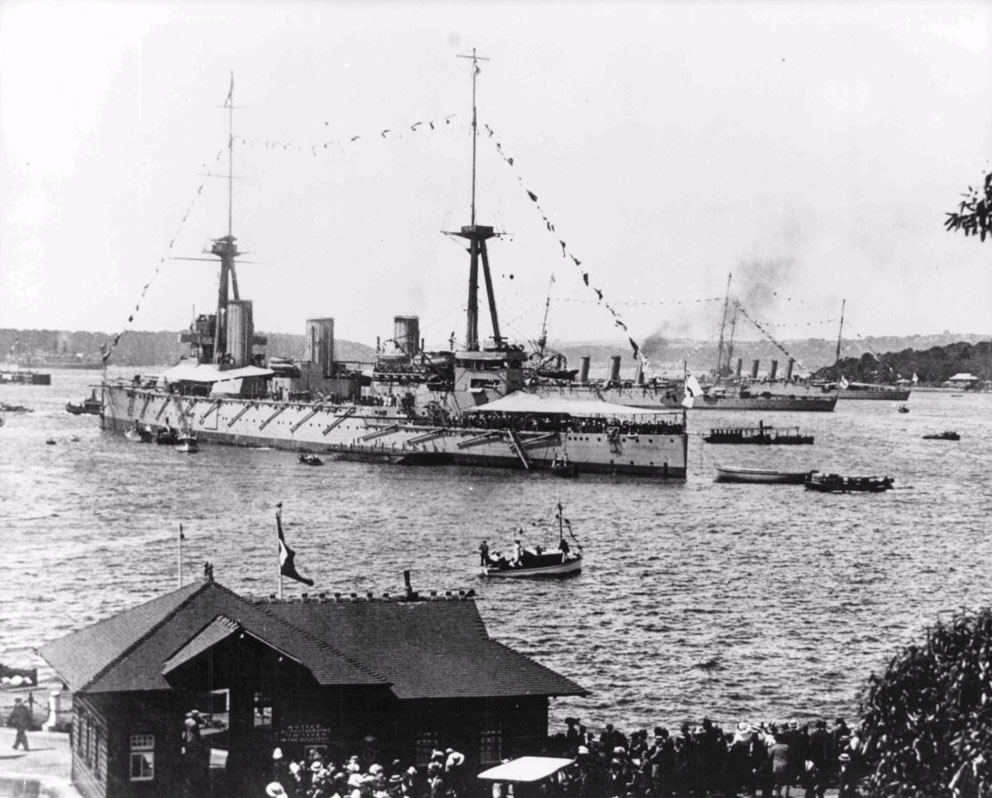

So the two battlecruisers were built, one for British service at New Zealand expense, the other for Australian service at Australian expense. The difference summed up much of the cultural contrast between the two Dominions. While the ‘fleet unit’ concept was scrapped by Winston Churchill during a 1912-13 effort to keep Britain’s naval estimates down, the Australian unit was left as the core of a Royal Australian Navy. HMAS Australia sailed into Sydney harbour for the first time in October 1913, and served in Australian and South Pacific waters during the early part of the First World War. She then transferred to the North Sea where she remained until the end of the war. Afterwards she returned to Australian waters, but was reduced to a nucleus crew and gunnery training ship in 1920, well ahead of the Washington conference that listed her – among many other British ships – for scrapping.[12]

My book on HMS New Zealand, covering the politics of the Australasian gifts in much more detail, is published by USNI Press. Check it out.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2024

[1] Edward Humphreys, ‘Some aspects of the federal political career of Andrew Fisher’, Master of Arts thesis, University of Melbourne, July 2005, p. 37.

[2] http://historichansard.net/senate/1909/19090708_senate_3_49/

[3] For discussion, Humphreys, p. 46.

[4] Nicholas Lambert (ed), ‘Australia’s Naval Inheritance’, Royal Australian Navy Maritime Studies Programme, Department of Defence (Navy), Canberra 1998, ‘Notes of the proceedings of a conference at the Admiralty on Tuesday 10 August 1909, p. 181

[5] Ibid.

[6] The term ‘battle cruiser’ – two words – was formally adopted by the Royal Navy in October 1911.

[7] https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/foxton-justin-fox-greenlaw-6230

[8] https://historichansard.net/hofreps/1909/19090630_reps_3_49/#debate-2-s6

[9] For discussion see Humphreys, p. 48.

[10] https://historichansard.net/hofreps/1911/19111108_reps_4_61/#subdebate-3-0-s2. See also John Griffiths, ‘Australia and its screw’, https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/blog/hmas-australia-screw

[11] https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE00509b.htm

[12] See https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-australia-i

Interesting Article. A good read.