It is easy to declare that the Battle of Jutland – to the Germans, the battle of the Skagerrak[1] – fought over a hectic afternoon and night on 31 May-1 June 1916, was a tactical German victory and a strategic British one. The idea has become a trope in historical circles. But it also misleads, for the battle was more complex than that. T

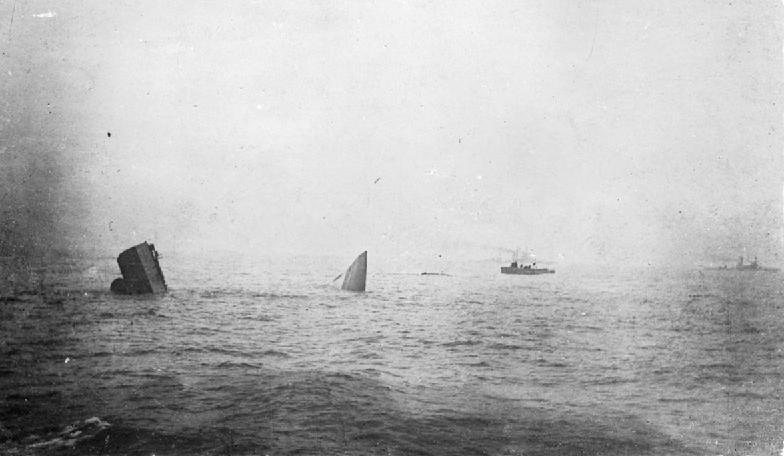

HMS Queen Mary blows up at Jutland, as seen from the German lines. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

There is actually quite a bit of mythology swirling around the outcome of Jutland – it has been suggested, for instance, that this battle swept the High Seas Fleet from the seas and kept it in harbour. In fact the High Seas Fleet next put to sea on 18 August, less than three months after Jutland, to bombard Sunderland.[2] It was the near-miss action of this sortie, and not Jutland, which convinced the German Naval Staff that U-boats were a better bet for reaching a decision at sea and led to their 6 October decision to recommence unrestricted U-boat warfare.[3]

As we saw in the previous article, the actual answer to ‘who won’ Jutland isn’t a statement – it’s a discussion, which has been going on in both popular and academic literature for a while.[4] Just about every argument has been offered; this article sums up some of the main themes. But in any event, much depends on how ‘victory’ is measured – whether in tactical and strategic outcomes, or in losses, or by some other accounting. However, with a few exceptions,[5] western thought tends to lean towards finding a ‘single’ answer even to complex issues, certainly popularly – and Jutland has been little different.

The arguments began almost as soon as the battle was reported; and back in the day, these were immediate and personalised, revolving around the competence of the Commander in Chief of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe. Much of the fury derived from the public definition of ‘victory’, which popularly meant scoring a crushing victory over Germany’s fleet. In fairness, that idea was also held to some extent within the Admiralty. And Jellicoe hadn’t delivered it. He certainly drove the High Seas Fleet from the field of battle, but the ‘second Trafalgar’ that the public viewed as the only real outcome had been elusive. When coupled with the fact that the Germans sank more British ships (without denting overall British superiority) the idea emerged that Jellicoe had somehow botched things.

Sir John Jellicoe as Admiral of the Fleet in 1919. Public domain, via Wikipedia.

That reduced the argument to a focus on Jellicoe’s tactical conduct. In reality this was a non-issue, as we saw in the previous article. Strategic naval thinking of the day was developing around the teachings of talented US naval thinker Alfred Mahan and others like him, in which the key objective was not destroying the enemy sea force (navy), but preserving national sea power (the merchant marine and the ability to sail the seas unimpeded). Destroying the enemy sea force was one way to do that – but it was risky given that merely having the ability to do so, through a superior fleet that could sail at any time, was as effective. Jellicoe did not have to win Jutland to maintain Britain’s blockade and keep the war going. However, he could lose the war if he lost that superiority. This concept stood at some tension, within Admiralty circles, with the historical measure of success – crushing the German fleet, which had some strategic advantages of its own in terms of freeing up resources. These two ideas; the new concept of ‘fleet in being’ versus older measures of ‘victory at sea’, were never resolved.

Certainly a crushing victory was the sole measure of success as far as the public were concerned, along with the idea that victory was measured in the number of enemy ships sunk. Just to pursue a counter-factual, let’s imagine Jellicoe had lost enough ships to lose British naval superiority. What then? He would have been cashiered (if he survived) or pilloried (if he didn’t) on the basis that what counted was keeping the fleet intact, so why try to get a victory at sea? In short, whichever way the battle went, anything other than a crushing victory was going to get him criticised.

That same focus on ‘numbers sunk’ and ‘crushing victory’ also buried the point that, by another valid and historical measure of victory – defined by the side left in sole possession of the field – Jutland was hands-down British tactical success. Scheer ran for home. The British did not.

A lot of it came down to details, which were gone over, post-fact, by people hostile to Jellicoe and looking for anything that could be twisted into a mistake in order to prove allegations of incompetence. One of the factors fanning the controversy was the way the battle was truncated. The fleets clashed only for an hour or so, late on 31 May in poor visibility. Jellicoe’s own flagship, Iron Duke, fired just 90 heavy shells during the entire encounter.[6] Some battleships managed less; Orion, for example, opened fire at 6.33 pm, but only got four salvoes away before her target – a Kaiser class battleship – disappeared into the mist at 6.37. They reopened fire at 7.15 pm on a Derfflinger class battlecruiser, getting six salvoes away, then ceased at 7.20 pm – and that was it. Nor were these full ten-gun salvoes: only some 51 AP shells were fired in all.[7]

The problem was that battle was never resumed, thus throwing weight, post-fact, on Jellicoe’s tactical decisions during the brief fleet encounter. Much criticism was of the ‘if only Jellicoe had…’ or ‘the last chance to…’ variety – all of it in hindsight and written, as Reginald Bacon pointed out, from the comfort of armchairs and with the details of post-war maps. [8]

The reality was that Jellicoe was working with what he knew and reasonably expected, and he was doing so on the basis that he had a superior force sitting between the Germans and their bases – and thus could avoid taking unnecessary risks. When he turned his fleet away from a mass German torpedo attack at the end of the second fleet encounter, at 7.22 pm,[9] he certainly did not think this was the last opportunity to maul them. Indeed, the High Seas Fleet was shortly within sight of the British Battlecruiser Fleet, and by 8.00 pm Jellicoe had the Grand Fleet on course to intercept, hoping to re-engage by about 8.25.[10]

That did not eventuate for various reasons, including growing dusk, where identifying ships became difficult. Jellicoe was also reluctant to press a night action, for which the Grand Fleet was ill-equipped.[11] But they remained between the German fleet and their bases, and nights were short at that latitude and time of year. Jellicoe had every expectation of renewing battle when light returned in the early hours of 1 June.[12] Had this happened, of course, the minutiae of his manoeuvres the evening before would have been of scarce import – and Britain would almost certainly have had a second ‘Glorious First of June’, 122 years after the first.[13]

As matters stand, a glance at a composite map of the entire series of fleet movements between 5.30 pm, as they approached, and full night at 9.00 pm (noting that the British were not using the 24-hour clock at the time) is telling: Jellicoe clearly had complete tactical control, leaving Scheer first moving in circles, then bouncing off the Grand Fleet as it continued to block his path. This speaks for itself, and had the encounters occurred a couple of hours earlier the results would almost certainly have been the crushing victory the British public wanted.

Main fleet action 31 May 1916 by GDR, via Wikipedia.

The controversy itself erupted almost immediately after the battle, triggered by the fact that the Germans got in first with the international media, trumpeting Jutland (Skagerrak) as a victory. Scheer was still trying to portray it as such in his memoir of 1921.[14] The Admiralty were laggard in responding, in part because they wanted to wait for despatches from Jellicoe, with the result that the Germans seized the moral high ground. And the Admiralty statement, when finally issued on 3 June, was cautious – it failed to mention that the Germans had run for home and had left Jellicoe in possession of the battlefield.[15]

Jellicoe’s own despatch did not come until July; but the issue was muddied by the fact that four major British warships – three battlecruisers and an armoured cruiser – had gone down in sudden explosions with tragic loss of life. British material losses were higher and, of course, that crushing ‘second Trafalgar’ had never been delivered.

Debate swirled around the personalities of the Admirals involved, in which the colourful and popular Battlecruiser Fleet commander at Jutland, Sir David Beatty, was pitted against the quiet and mathematical Jellicoe. The debate and gained pace in the early 1920s as the first memoirs emerged. They were driven in part by a book by Alexander Filson Young, With the Battlecruisers. Young was a journalist, but had served aboard Beatty’s flagship Lion in 1913 and again in the early part of the war. He had written then in glowing terms about Beatty.[16] The latter was apparently embarrassed by it – ‘nobody has ever achieved anything after being puffed up like that.’[17]

That did not prevent Young publishing what amounted to further pro-Beatty spin in With the Battlecruisers. This was written without reference to official papers – which Young was forbidden to access[18] – but nonetheless plumped up Beatty’s reputation and cast severe doubt on some of the Admiralty statements made after the battle of Dogger Bank in 1915.[19]

Jellicoe was not in England to respond; he had been under a cloud at the Admiralty not just because of Jutland but also thanks to his approach to the U-boat crisis of 1917 when he was First Sea Lord. In 1919 he was bundled off aboard the battlecruiser HMS New Zealand, to report on Indian, Australian and New Zealand defence policy.[20] Soon after his return to Britain he was appointed Governor-General of New Zealand,[21] arriving back in Wellington aboard the Corinthic in late September 1920.[22]

Sir John Jellicoe (centre) as Governor-General of New Zealand, picnicking on Ninety Mile Beach in January 1924. He had a personal repute for being polite, kind, and thoughtful towards others. Northwood, Arthur James, 1880-1949. Lord Jellicoe picnicking at 90 Mile Beach. Northwood brothers :Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-006355-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22313306

The Jutland controversy exploded into new life in August 1924, while Jellicoe was still in New Zealand.[23] Scheer was interviewed by the Daily Express and announced that had Jellicoe deployed differently at Jutland when the fleets collided – to starboard instead of port – he might have decisively beaten the High Seas Fleet. The interview was widely reported.[24] Three days later Young waded in, insisting Jellicoe had been too defensive. It was on the back of this that Bacon then wrote a full-length book, The Jutland Scandal, [25] to refute both Young[26] and – as it happened – Winston Churchill, who had also been critical of Jellicoe and who Bacon described as writing ‘from his armchair in the clear atmosphere of his library.’[27] Along the way Bacon quoted Young extensively, who responded by trying to take Bacon to court for copyright infringement.[28] This was amicably resolved; Bacon’s book had virtually sold out and the second edition, of 1925, removed the offending words.[29]

Admiral Sir Reginald Hugh Spencer Bacon (1863-1947), seen here in 1915; first captain of HMS Dreadnought and a loyal supporter of Jellicoe. Public domain, via Wikipedia.

That did not end debate over the battle, which continued in historical circles. The argument over who won and general evaluation of the decisions and tactics involved has inevitably featured in every book on Jutland since – and with reason. As we have seen here, it is a debate that cannot be reduced to a few words; and much depends, ultimately, on how ‘victory’ is actually defined. This is a point on which there is no single answer, for each of the viewpoints – whether the battle had strategic import; whether the British gained tactical victory by being in sole possession of the field afterwards, or whether the Germans perhaps gained tactical victory instead by escaping the trap – has its merits.

In a situation where the obvious answer may well be ‘all of the above, in various ways’, the actual answer to the question ‘who won’ can only be a discussion. And in that discussion, particularly given that he did not lose sight of the fact that he didn’t have to win the battle in order to keep the war going, we must acknowledge Jellicoe’s contribution as being considerably greater than is often admitted.

For more on matters naval, check out my book The Battlecruiser New Zealand: a Gift to Empire. Click to buy.

To access the other latest articles, check out the Home Page of the Navy General Board.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2018

Notes

[4] For example, Andrew Lambert ‘Writing the battle: Jutland in Sir Julian Corbett’s Naval Operations’, The Mariner’s Mirror, Vol. 103, No. 2, May 2016, pp. 175-195; or Captain Donald Macintyre, Jutland, Evans Brothers, London 1957, pp. 186-195; Nigel Steel and Peter Hart, Jutland 1916: death in the grey wastes, Cassell, London pp 417-435.

[5] For instance, Eric Grove, ‘The Jutland paradox: a keynote address’, The Mariner’s Mirror, Vol. 103, No. 2, May 2017, pp. 168-174.

[6] http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/H.M.S._Iron_Duke_at_the_Battle_of_Jutland, accessed 12 July 2018.

[7] http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/H.M.S._Orion_at_the_Battle_of_Jutland, accessed 12 July 2018. My great uncle was aboard at the time, in fire control.

[8] Bacon, The Jutland Scandal, p. 206.

[9] Steel and Hart, p. 263.

[10] Donald McIntyre, Jutland, 1957, Evans Brothers, London 1957, pp. 143-144.

[11] Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, The Grand Fleet 1914-1916: its creation, development and work, Cassell & Co., London 1919, pp. 372-374.

[12] Ibid, p. 374.

[13] The first was in 1794 when Lord Howe defeated a French force off Ushant.

[14] Scheer, pp. 176-177. His wording was framed around justifying a German navy.

[15] Nigel Steel and Peter Hart, Jutland 1916: death in the grey wastes, Cassell & Co., London 2004, p. 422.

[16] http://richarddnorth.com/archived-sites/filsonyoung/biography/part-5-admiralty-spy-1914-19/22-admirals-fisher-and-beatty/, accessed 12 July 2018.

[17] Beatty to Ethel Beatty, 11 April 1913, in ibid.

[18] Filson Young, With The Battlecruisers, reprint 2016, Appendix II, Secretary of the Admiralty to Young, 30 October 1920, p. 115.

[19] http://richarddnorth.com/archived-sites/filsonyoung/biography/part-6-editor-1919-24/31-attacking-the-admiralty/, accessed 12 July 2018.

[20] Ian McGibbon, ‘Jellicoe, John Henry Rushworth’, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4j4/jellicoe-john-henry-rushworth, accessed 11 July 2018.

[21] Ibid.

[22] The Dominion, 8 September 1920. It is commonly stated, but incorrect, that he was brought out aboard HMS New Zealand.

[23] McGibbon, ‘Jellicoe’.

[24] For example, The Daily News (Perth), 7 August 1924, p. 7.

[25] Noted in Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon, The Jutland Scandal, Hutchinson & Co, London, 1925.

[26] http://richarddnorth.com/archived-sites/filsonyoung/biography/part-7-making-airwaves-1924-30/37-the-jutland-controversy/, accessed 12 July 2018.

[27] Bacon, The Jutland Scandal, p. 206.

[28] http://richarddnorth.com/archived-sites/filsonyoung/biography/part-7-making-airwaves-1924-30/37-the-jutland-controversy/, accessed 12 July 2018.

[29] This was Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon, The Jutland Scandal, Hutchinson & Co, London, 1925, second edition.