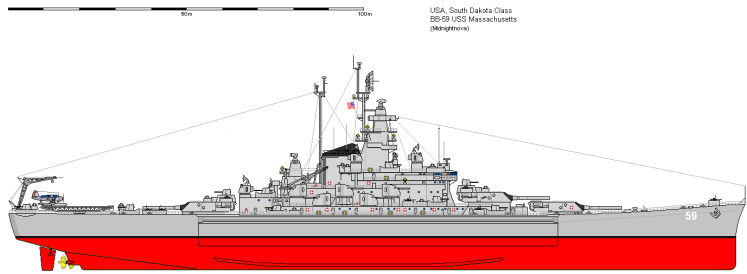

One of the most ingenious battleship types of the Second World War was the US Navy’s four-strong South Dakota class, which packed excellent fire-power, armour protection, good range and reasonable speed into a Treaty-limited displacement.

USS Massachusetts, one of the South Dakota class. Artwork by Midnightnova, via Shipbucket. CC 4.0 non-commercial license.

In part the design was a result of the requirements the US Navy had for its ships; other nations had differing needs – including particular range, expected operational use and issues such as dockyard size limits – and hence different engineering solutions within the treaty framework. The French went for more speed but only 15-inch guns, for example. However, in general, no other battleships of the day matched the South Dakota‘s excellent combination of characteristics within the Treaty limit, notably the fact that she carried 16-inch guns and had a good immunity zone against a ship of similar armament, something thought almost impossible to combine with good speed on the displacement.

What isn’t always realised, however, is that the British Admiralty’s designers were looking at a treaty-limited ship with similar fire-power, speed and protection at the same time – and for the same reasons – but were hampered by the state of Britain’s finances during the inter-war years. This had also taken a toll on the British arms industry. The whole was framed by the international naval limitation system that began with the five-power ‘Washington Treaty’ of 1922. This killed a nascent naval race and constrained ship numbers, displacement and gun calibre. It also imposed a battleship-building ‘holiday’, which contributed to the dramatic reductions in Britain’s arms industry and general industrial capacity. At Treasury urging, the British government then engaged in efforts to extend the system, first with the London Naval Treaty of 1930 and then the Second London Naval Treaty of 1936. This last maintained displacement limits of 35,000 tons but initially restricted new construction to 14-inch guns. [1] In practise only Britain, France and the United States paid attention to the limits; Italy and Germany claimed they were compliant, but were not; and Japan was threatening to withdraw altogether.

That attitude guided the final result: the 14-inch limit was pushed by the British for financial reasons, but the treaty contained an ‘escalator clause’. If Japan failed to ratify by 1 April 1937, guns could revert to the earlier agreed limit of 16 inches.[2] The outcome, as described in an earlier article, was that the first new US battleships, the North Carolina class, were designed with 14-inch weapons – and armoured accordingly – but ordered up-gunned to 16-inch in November 1937, after North Carolina had been laid down.[3] The likelihood of up-gunning had been anticipated and capacity designed in to allow it; but this was something the British could not do for their King George V class. [4]

USS Massachussets under-way during July 1944, in Measure 22 camouflage. Public domain, via Wikipedia.

The ideal in the post-escalator environment was a fast battleship with 16-inch guns that had a good immunity zone against 16-inch fire. Achieving that within the 35,000 ton displacement limit was challenging; but that was where designers on both sides of the Atlantic went for follow-up ships. The main result was the US Navy’s South Dakota class. Their armour was designed using the 16-inch/45 calibre weapons of the older Maryland class as a yardstick, with an immunity zone of 17,700 to 30,900 yards against such fire.[5] This was achieved on limited displacement by reducing citadel length. Calculations showed a 7 percent reduction in vulnerable area by comparison with North Carolina.[6] Another significant advantage came from the latest propulsion technologies, which provided 130,000 hp for 27 knots contract design speed.[7] This was fast by earlier US standards although, even before the ships entered service, was seen as relatively modest.

Inevitably there were compromises. The compact superstructure created issues of blast interference with secondary and anti-aircraft weaponry. On the basis that a well-balanced design was measured by armour able to resist a ship’s own main armament, the armour system fell below par when the 2700 lb Mk 8 16-inch shell was introduced. This did not reduce the effectiveness against likely opponents. However, there were also concerns about the anti-torpedo protection. This improved on the North Carolina, but because working and living spaces were still above the system, a review board warned of potential casualties from a torpedo hit, along with risk of progressive flooding above the system.[8] In 1945, after analysis of collision damage to the USS Indiana, a study also showed that if the third deck between bulkheads 113 and 125½ was flooded as a result of significant hull damage aft, a South Dakota class ship would potentially sink by the stern.[9]

Such issues were inevitable with any design, however well considered. However, the key issue about the ‘Sodaks’ was the fact that they achieved such remarkable all-round capability on a limited displacement. They were by far the best of the ‘Treaty limited’ battleships and an excellent demonstration of US technical ability and industrial capacity.

USS South Dakota during the battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, 26 October 1942, wreathed in smoke from her anti-aircraft fire. Public domain, via Wikipedia.

The British problem by the late 1930s was that their new battleship class, the King George V’s, had been built around 14-inch guns. As we saw in an earlier article, it was challenging even on that armament to include the protection the Admiralty thought necessary. Originally just two were planned, with 16-inch gunned ships for the 1937 programme. However, that tripped over timing and Japanese diplomatic intransigence, which we will explore in the next article: suffice to say that the three 1937 ships had to be repeat King George V’s.

This did not stop the Director of Naval Construction, Stanley Goodall, and his team – including the battleship expert, Herbert S. Pengelly – from exploring ways of building 35,000 ton ships with 16-inch guns for the 1938 programme.[10] Japan rejected the treaty on 31 March 1937, just 24 hours before the deadline, but it was June before their government stated it would no longer observe any limits. The problem was that the British government was still bound by them. Admiralty thinking – founded in what was known of the Japanese financial position and industrial capacity – was that the Japanese were likely to build ships of maybe 43,000 tons with 16-inch guns, and the question became how to match that on 35,000 tons.[11] Nobody, either in the United States or Britain, expected the Japanese were capable of – and intending – to build 18-inch gunned ships of displacement more than 185 percent over the limit.

By July, Pengelly had discovered it was possible to build a King George V to the 35,000 ton limit with six 16-inch guns in two triple turrets. However, a nine-gun ship required 37,500 tons, even with speed cut to 27 knots and hangar facilities deleted in favour of a catapult atop one of the turrets. To retain the speed and hangars of the King George V added a further 1000 tons to a design already out of scope.[12] Another option was slashing horsepower, dropping speed to 25 knots,[13] but both that and a Nelson-style turret arrangement were rejected.[14] Pengelly kept working on the numbers and concluded that a King George V with nine 15-inch guns could be built on 35,450 tons. Or a nine 16-inch gunned version could be built at 37,000 tons.[15]

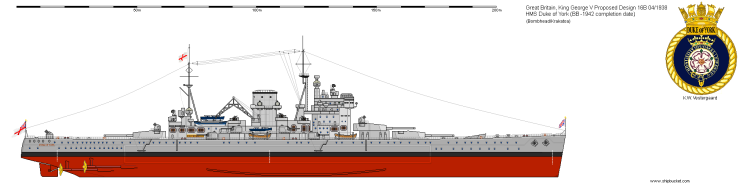

Conceptual drawing of a ship built to design 16B/38, by Bombhead and Krakatoa, via Shipbucket. CC 4.0 non-commercial license.

This last was too heavy, but Pengelly then trimmed the extent of belt armour and ammunition stowage, deleted the aircraft, and limited speed to 28 knots. This design was ready by December 1937 and dubbed 16A/38. In all of these, by comparison with the South Dakotas, we have to remember that the British were building to different detail specification with a heavier armoured belt, partly a result of their decision to revert to vertical external side armour, which contrasted with the lighter US sloped internal system. The reasoning reflected the usual swings-and-roundabouts issues facing engineers: each approach had their own advantages. The Admiralty also had particular requirements for protection that the US Navy’s Bureau of Construction and Repair did not.

The problem with 16A/38 was that the Admiralty’s Engineer in Chief, Vice-Admiral Sir George Preece, wanted to repeat the King George V machinery. This added weight, making standard displacement on the resulting 16B/38 some 35,650 tons. Pengelly also sketched a design to the same concept with a dozen 14-inch guns in quads, at 35,330 tons.[16] The issue of aircraft rankled; but while Pengelly produced a derived design with a hangar and a secondary armament of just eight 5.25-inch guns, 16C/38, he apparently did not like it.

What stands out about Design 16B/38 is the broad similarity with the South Dakota class. Both ships had comparable main armament and protection with similar speed. Obviously they were far from identical, but the relationship was much the same as between North Carolina and King George V, described in a previous article. All represented engineering solutions framed by national requirements and design philosophies, intended to meet an identical set of treaty-driven limitations. Had the British built Design 16B/38 or its variants, one difference would have been operational: US propulsion technology was more fuel-efficient. There was also a structural difference. Thanks to more generous budgets, the US Navy made more extensive structural use of special-treatment steel in its warships. The British, hampered by financial restrictions, could use their equivalent ‘Ducol’ steel only in limited quantities.

As it happened, while the United States built four South Dakotas,[17] the British designs remained paper projects. The US Navy had not been entirely happy with the 27-28 knots of its new battleship classes and in early 1938 began looking at faster vessels.[18] When coupled with Japanese refusal to comply with any limits the result was a diplomatic effort to re-negotiate the displacement restriction.[19] We will explore what that meant for Britain in the next article. For the United States the practical result was an outstanding class of battleships – extremely fast, armed with the superb 16-inch/50 calibre weapon, well armoured, and long-ranged; the Iowas.[20]

For more on naval history, check out my book The Battlecruiser New Zealand: a Gift to Empire. Click to buy.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2018

Notes

[1] Detailed in Norman Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, Seaforth, Barnsley, 2015, pp. 294-295.

[2] Naval Limitation Treaty (Second London Naval Treaty) of 25 March 1936, Part 2 Article 4 (2), text at https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000003-0257.pdf.

[3] William H. Garzke and Robert O. Dulin, Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II, McDonald and Jane’s, London, 1976, pp. 34, 47-49.

[4] William H. Garzke and Robert O. Dulin, Battleships: British, Soviet, French and Dutch Battleships of World War II, Jane’s Publishing Company, London, 1981, p. 173.

[5] Garzke and Dulin, Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II, p. 89.

[6] Ibid, p. 72.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, p. 96.

[9] Ibid, p. 82.

[10] Garzke and Dulin, Battleships: British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, p. 173.

[11] Friedman, p. 325.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid, p. 326.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid, p. 327.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Garzke and Dulin, Battleships: United States Battleships of World War II pp. 73-88.

[18] Ibid, p. 107.

[19] Ibid, p. 109, are incorrect to state that the increase was automatic.

[20] See ibid, pp. 109-151.

Recent Comments