In the mid-1880s the British began building two new battleships as part of the so-called ‘Northbrook’ programme, a massive burst of naval expenditure to which government reluctantly agreed in early December 1884.

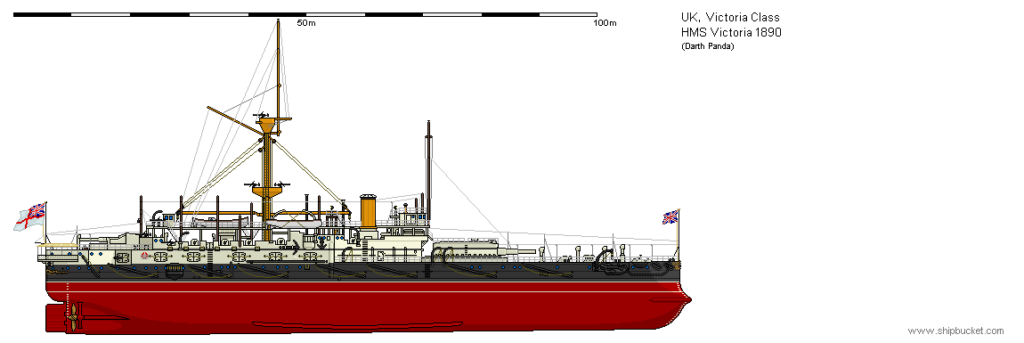

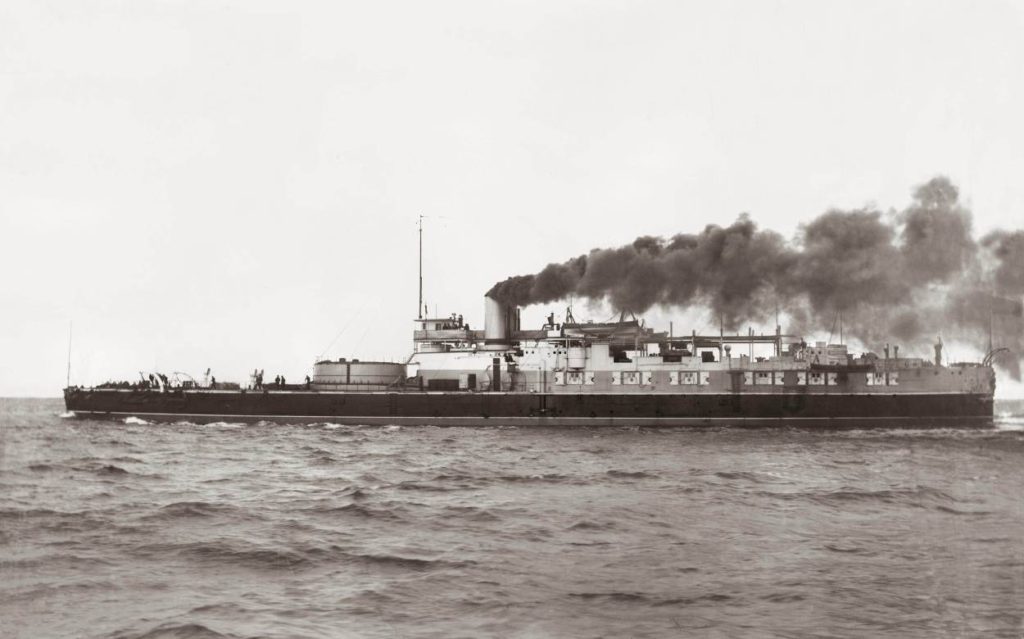

What then emerged from the drawing boards of the Director of Naval Construction, Nathaniel Barnaby, and his team were – by later standards – perhaps the oddest looking battleships the British built. The ships were sometimes nicknamed ‘pair of slippers’ at the time because the low foredeck with its single turret, backed by a higher superstructure running to the stern, looked like that style of footwear.

The designs for the two ships had been in development for some time before they were authorised, probably as part of the effort to inform the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Northbrook, about the scale of costs. This meant he could give a potential naval programme a concrete shape before Cabinet approval was sought. The prior battleship designs, the ‘Admirals’, had been displacement-limited to keep costs down. However, the Director of Naval Construction, Nathaniel Barnaby, assumed that the fiscally-driven displacement limits would be lifted, and began exploring a range of heavier designs from late 1884.[1]

The new ships were based not on the ocean-going ironclads and central-battery ships of the 1860s and 1870s, but on the shorter-range mastless coast defence ships of the same period. This had been true of all Britain;’s so-called ‘mastless’ battleships – a period term meaning they did not rely on sails for propulsion – but there was no experience or consensus yet on exactly how the ships should be laid out, or what their armament should include.

What finally emerged for the two ‘Northbrook’ battleships were enlarged versions of the coast-defence ‘turret-ram’ Conqueror. That design, however, was only reached after a number of gyrations, some quite radical – all of which underscored the varied nature of thinking within the Admiralty at the time. As we saw in earlier articles, this was already evident in the six ‘Admirals’ laid down in 1880-83. Although often considered a ‘class’ because of a common general layout and design features, they actually mixed and matched several hull sizes and armament. And while – with hindsight – we know that their general layout became a model for the battleships of the 1890s, that point was not obvious in the mid-1880s.

As a result, Barnaby’s first sketches for the ‘Admirals’ successors, from early September 1884, proposed something very different. Increased displacement meant that turrets could be included without compromising other features, and Barnaby’s initial sketch proposed an 11,500 ton battleship with three 13.5-inch guns in three single turrets, one forward and one on each beam amidships, backed by no less than 18 6-inch guns. Speed was 16.5 knots, and Barnaby proposed to armour this ship only with a thick deck, supplemented by turret armour and associated protection.[2] This concept was being bandied about in naval circles at the time, and had been actually adopted by the Italians.[3]

The remarkable part was the proliferation of so-called ‘secondary’ weapons, guns of far smaller calibre than the main armament. But we have to consider these in the terms of the day. As we saw in an earlier article, by this time the 6-inch gun was viewed in many ways as a key part of the armament, able to return to the classic ‘hail of fire’ of Nelsonic days in ways that slow-firing heavy guns could not. Smaller guns were thought to be effective against unarmoured or lightly armoured parts of any enemy vessel at the ranges expected of the day. The idea was that a battleship with a heavy secondary armament might not sink an opposite number with those guns alone, perhaps not even stop it firing its heavy guns. But it could wreck the ship as a going concern.

This, too, was a return to the concepts of the days of sail and ‘wooden walls’, when cannon fire could devastate an opposing ship and essentially knock it out of battle, but not often sink it. At Trafalgar, for instance, the Franco-Spanish force lost the majority of their ships by capture. Many of the captured ships were then abandoned and sunk, by order, when a storm caught the British fleet; but they had not succumbed to battle.[4]

Barnaby’s first idea for the ‘Northbrook’ battleships apparently never proceeded beyond a basic sketch, but it underscores the variations considered credible at the time. His next ideas, in late October 1884, included cost estimates[5] – as we might expect for sketches being developed to inform a budget. In November, in a further sign of the variability of naval thinking, Barnaby produced two contrasting designs: a modified ‘Admiral’, (‘Design D’) equipped with two turrets mounting 12-inch guns, and a modified Conqueror (‘Design E’), with just one turret forward but two 13.5-inch guns. Both, however, had the same speed and displacement.[6]

This last was chosen for further development, although not before other officials waded into the discussion. George Tryon, Permanent Secretary for the Admiralty at the time, wanted ‘barbette’ ships that could operate in relatively high seas. He also thought high speed was essential, and backed a design that was not in consideration but which offered two knots additional speed. However, his voice went unheard, apparently in part because of a change in the Board of Admiralty.[7]

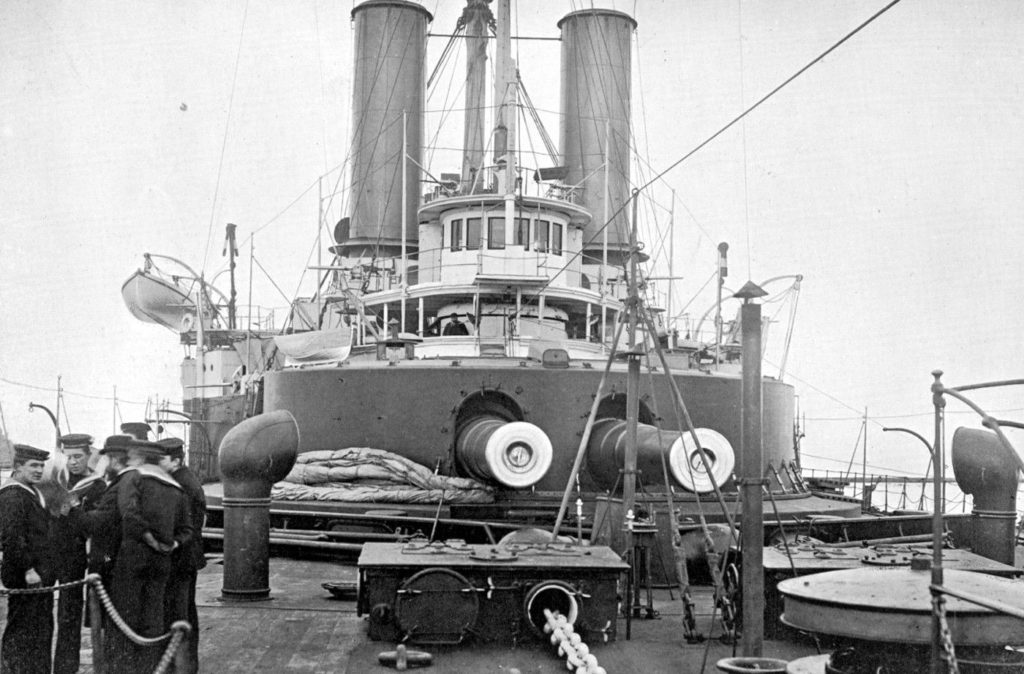

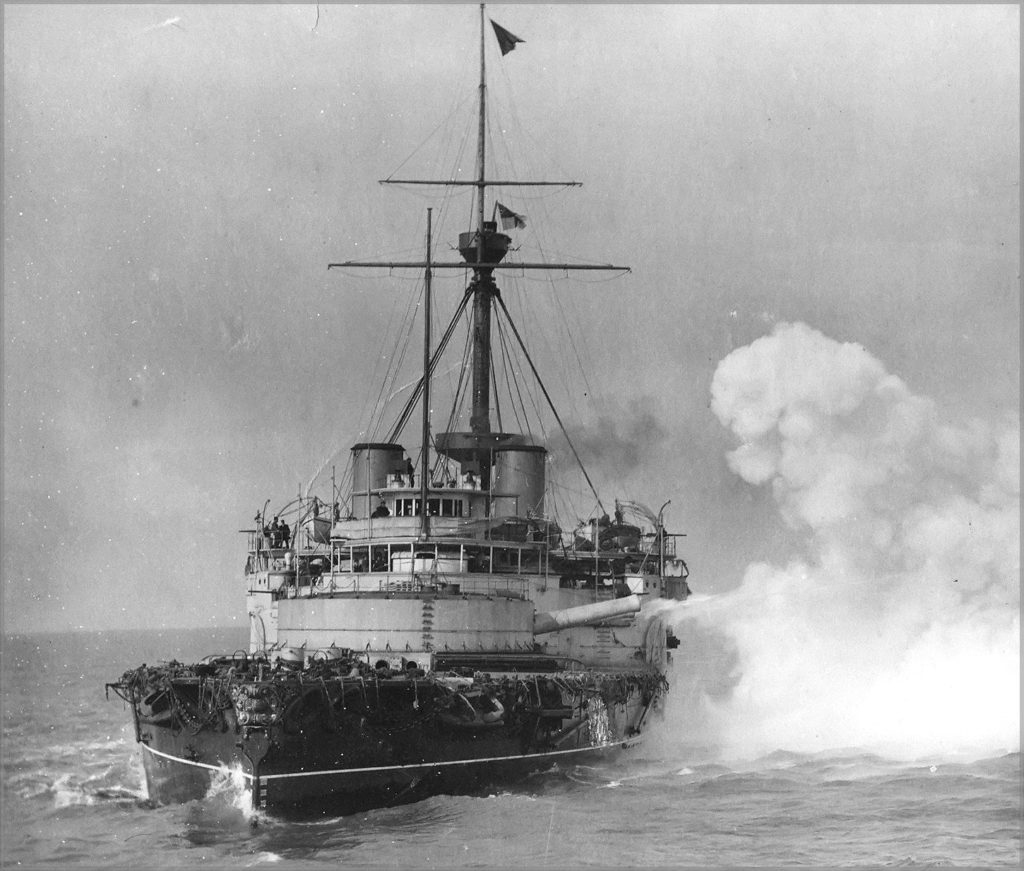

The final design for the two ‘Northbrook’ battleships emerged with a dozen 6-inch guns, a single 9.2-inch aft, and two colossal Elswick 16.25-inch guns in a huge turret forwards. These last were the biggest guns fitted to a British battleship to that time,[8] and their engineering stretched available technology. With a displacement of 10,470 tons, the final design was in similar league to the ‘Admirals’, but below some of the original sketches.[9] As built, the aft 9.2-inch was transmuted to a Woolwich-designed Mk II/III/IV 10-inch 32-calibre gun firing a 500 lb shell.[10]

The ships were given good speed by 1880s standards; 16 knots at natural draft and 17.3 with forced draft. They were also equipped with vertical triple expansion engines, the first specified for a British battleship. Such engines had been in development for merchant marine use for some time.[11] They relied on higher boiler pressures than previously standard; typically 135 psi, against the 90 psi of the ‘Admirals’.[12] The main advantage of triple-expansion engines for a world-spanning Empire such as Britain’s was their fuel efficiency. This development, coupled with the Northbrook expansion of worldwide coaling stations, resolved the problem of global range that had dogged early steam warships.

There was a cost. Triple-expansion engines were taller than older horizontal engines, creating issues fitting them into warships where heavy equipment ideally needed to be low, and certainly below an armoured deck. The issues were soluble; naval engineers had, by this time, broadly mastered the mathematics of calculating metacentric height and other ship characteristics.[13] However, triple expansion engines complicated the problem.

In the end, and despite the potential for larger and costlier ships, both ‘Northbrook’ battleships were little heavier than the ‘Admirals’; and their unit cost, in the end, was not significantly more.[14] The interesting point, in terms of understanding the place of the pair in naval history, is again in the mix of armament they carried. It is easy, looking back, to consider that a ship with just two slow-firing heavy guns and minimal fire-control by later standards was never going to hit anything much at range. However, as we have seen, the 6-inch was also a credible fleet weapon of the day. As designed, the pair had more 6-inch guns than the preceding ‘Admirals’. Their fire was reinforced by the 10-inch gun aft, faster-firing than the 16.25-inch weapons and capable of mastering moderate thicknesses of armour. The main down-side was that all this armament was largely unprotected. The 6-inch battery, for instance, was screened with 6-inch bulkheads against raking fire, but its protection was not comprehensive.[15]

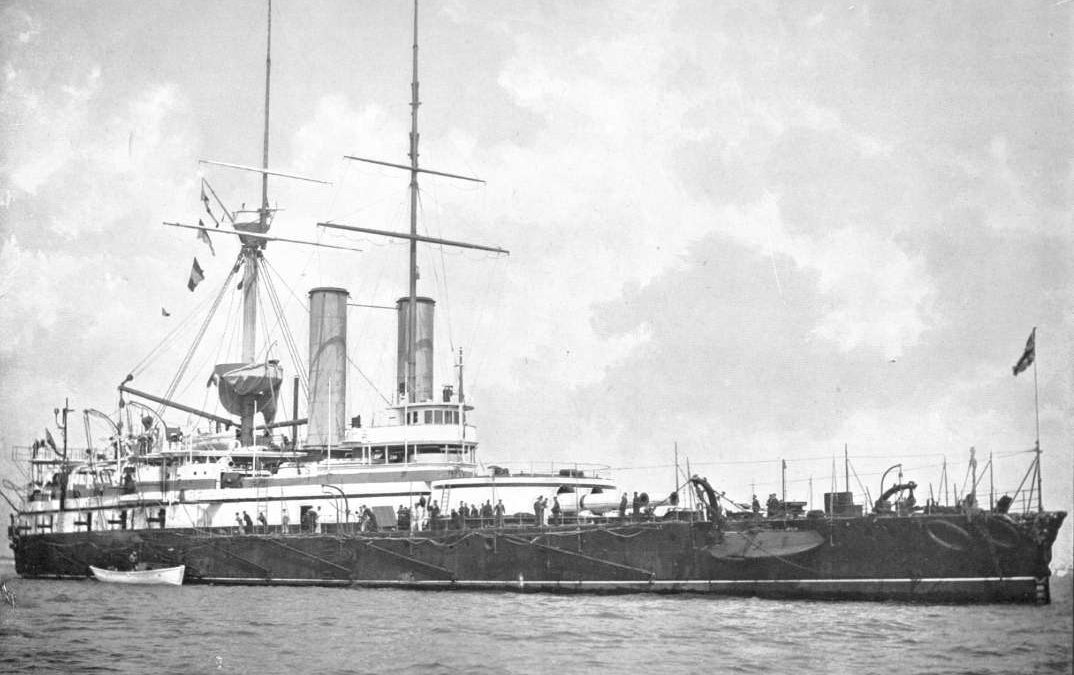

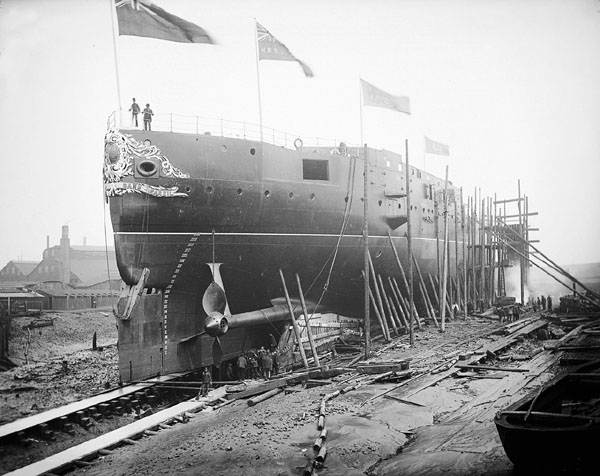

Like their predecessors, both ships took years to complete. They were originally called Renown and Sans Pariel, but in honour of the monarch’s fiftieth jubilee, Renown was renamed Victoria in March 1887, just two months before launching. She was completed in March 1890 with short funnels, later extended. Sans Pariel, completed in July 1891, always had longer funnels.[16] In what later presented as curious, the funnels were side-by-side amidships. This was a consequence of an attempt to protect the 16.25-inch powder magazine by putting it amidships between the boiler rooms, a concept retained until the Majestic class of the early 1890s.

Both ships were also built to ‘citadel’ principles, meaning that – in theory – their ends above the armoured deck could be riddled without risking loss of the ship. That system, however, did not stand Victoria in good stead in June 1893, as we shall see in the next article.

This article was about some of Britain’s first battleships. For details of some of Britain’s last, and particularly the financial constraints that wrapped their construction policies, check out my book Britain’s Last Battleships.

[1] Norman Friedman, British Battleships of the Victorian Era, Seaforth, Barnsley 2018, p. 198.

[2] Ibid, p. 198.

[3] See also J. D’A Samuda, ‘Armoured ships and modern guns’, Transactions of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects, Vol. 23, London 1882, pp. 1-12.

[4] See, e.g. https://www.britishbattles.com/napoleonic-wars/battle-of-trafalgar/, accessed 15 October 2019.

[5] Friedman, p. 199.

[6] Ibid, p. 199.

[7] Ibid, p. 204.

[8] In hindsight, they were the biggest guns ever fitted to a British battleship, although a single 18-inch gun was fitted to the ‘large light cruiser/light battlecruiser’ HMS Furious, and later to a monitor.

[9] Roger Chesneau and Eugene M. Kolesnik (eds), Conway’s All The World’s Fighting Ships 1860-1905, Conway Maritime Press, London 1979, p. 30.

[10] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_10-32_mk1-4.php, accessed 27 August 2019.

[11] Richard Sennett and Henry J Oram, The Marine Steam Engine, Longmans, Green & Co, 1899, https://www.naval-history.net/WW0Book-Sennett-MarineSteamEngine.htm, accessed 27 August 2019.

[12] Chesneau and Kolesnik, p. 30.

[13] For instance, see William Henry White, A Manual of Naval Architecture, John Murray, London 1877.

[14] Friedman, p. 203.

[15] Chesneau and Kolesnik, p. 30.

[16] Ibid, p. 30.

Recent Comments