HMS Agincourt, the one ship class dreadnought, was affectionately known amongst her crew as ‘The Gin Palace’, in a reference to her luxurious fittings and as a corruption of her name, ‘A-Gin-Court’, pink gin then being a popular drink amongst Royal Navy officers. She was an unusual vessel in both design and history and well worth taking sometime to study.

Her story opens two decades before her keel was even laid down, in 1889 with a coup in Brazil that saw the Emperor Dom Pedro II deposed. In addition to that, there was a naval revolt in the years 1893 and 1894, which left Brazil’s navy in a position where it was unable to even care for its existing fleet, let alone consider the building of new vessels. In 1902 Chile was to sign a pact limiting both Argentina’s and her own navy, as part of treaty resolving the boundary dispute between the two countries. The agreement called for the two navies to retain any vessels built in the interim, most of which were by then far more modern and powerful than Brazil’s ships. The Brazilian Navy had also lagged behind in naval tonnage with Chile’s total tonnage standing at 36,896 long tons ( a long ton is an British measurement), (37,488 tonnes), Argentina’s at 34,425 long tons (34,977 tonnes), and Brazil coming in at third place with 27,661 long tons (28,105 tonnes). This despite the fact that Brazil’s population stood at nearly three times that of Argentina’s and almost five times that of Chile.

The start of the twentieth century was to witness a world wide demand for coffee and rubber, gifting Brazil with an unforeseen source of revenue. Baron of Rio Branco was Brazil’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, and was involved in the defining of his country’s borders, with all of its neighbors. He was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1902 and was to retain the office until 1912, under four different Presidents, a feat unequalled in Brazilian history. The Baron spearheaded a drive by a number of prominent Brazilians to have the worlds leading nations recognize Brazil as an international power. In 1904 The National Congress of Brazil duly authorized a large naval program. The Law number 1452 was passed on the 30 December 1905 and authorized £4,214,550 (£470,262,208@2016) for a new program of warship construction. In 1906 a further £1,685,820 ( £188,104,883@2016)was allocated. These two programs provided for an expansion of Brazil’s navy with the ordering of three small battleships, three armored cruisers, six destroyers, twelve torpedo boats, three submarines, and two river monitors. Later the Brazilian government would cancel the armored cruisers, due to financial restrains. The Minister of the Navy, Admiral Júlio César de Noronha, signed a contract with Armstrong Whitworth of England, for the three small battleships on 23 July 1906.

The British shipyard was authorized to build two dreadnought battleships, Minas Gerais and São Paulo, and this, not really that unsurprisingly, started a naval arms race between Brazil and her neighbors, Argentina and Chile.

The launch of HMS Dreadnought would change everything, introducing a new style of capital ship, the ‘must-have’ thing in the South America navy’s. As a result the Brazilian Navy reconsidered its purchases. In March 1907, Brazil signed a contract for three Minas Gerae class battleships. Two ships would be constructed immediately by Armstrong Whitworth and Vickers, with a third vessel following in the next year or two.

Argentina and Chile were both alarmed at Brazil’s actions and cancelling their 1902 treaty, sought to obtain dreadnoughts of their own. Argentina placed her orders with the American company, Fore River Shipbuilding Company. The Argentine orders triggered another wave of the South American naval-race with Chile deciding that now she to needed a dreadnought and other smaller South American powers such as Uruguay, Peru, and Venezuela ordered an assortment of cruisers and gun boats. Brazil had already approved her three dreadnoughts. The first two were only on the design board at this stage but already they were being trumped by the more powerful twins Argentina had just ordered from the USA. Brazil’s Navy Minister Admiral Alexandrino de Alencar wanted not any dreadnought but one that was to be more powerful than any found in or building in any other navy. He fore-saw the ship armed with twelve 14-inch guns, fourteen 6-inch, and fourteen 4-inch guns on a displacement of 31,600-tons. Not unnaturally Armstrong’s their designer, Tennyson d’Eyncourt, were delighted with de Alencar’s vision. The new ‘super’ dreadnought would only to clearly unbalance the equilibrium that existed between the South American navies, and this leap in both size and armament couldn’t be ignored by the other navies of the continent. After negotiations, Armstrong’s, a favorite with the Brazilian Navy as a source of its warships, won the contract for the third Brazilian dreadnought, designed to the ‘vision’ of de Alencar. This new ‘super-dreadnought’ was to be named Rio de Janeiro, but along the River Tyne she would be known as ‘Design 690’ or “The Big Battleship”.

By this stage the Brazilian Navy had divided into two schools of thought over the question of the main calibre for their dreadnoughts. The outgoing navy minister was in favour of increasing the 12-inch guns mounted on board the Minas Geraes class, but the incoming minister, Admiral Marques Leão, was in favour of retaining the smaller but faster-firing gun. The series of events is unclear, but it seems that Leão used his access to the President to argue his case.

In the meantime the relationship between Brazil and Argentina improved but the coffee and rubber boom was losing its steam. Brazil tried to renegotiate with Armstrong onthe cancellation of their third dreadnought from the contract, but without any success. Brazil was forced to borrow the funds she required for her naval programme. A number of other events would most likely influenced the final decision as well. In November 1910 Revolt of the Lash [1], the heavy payments on loans taken out for the dreadnoughts, and a failing economy that had resulted in high government debt compounded by budget deficits. But by May 1911, the President had made his choice, ‘When I assumed office, I found that my predecessor had signed a contract for the building of the battleship Rio de Janeiro, a vessel of 32,000 tons, with an armament of 14 in. guns. Considerations of every kind pointed to the inconvenience of acquiring such a vessel and to the revision of the contract in the sense of reducing the tonnage. This was done, and we shall possess a powerful unit which will not be built on exaggerated lines such as have not as yet stood the time of experience’

The new contract between Armstrong’s and Brazil did however contain an unusual escape clause. In late 1910 when the contract was signed, there was a change in administrations scheduled in Brazil for that November. The contract stated that the new administration must ratify and approve it. The new minister of the Navy was to be Admiral Marques Leão. Whilst Armstrong’s had been negotiating with de Alencar and the outgoing administration in 1910, Leão had been touring the shipyards of Europe. The German company of Krupps were determined to win Leão over to their camp. The Germans were aware that Armstrong’s had already won the contract for the 3rd Brazilian dreadnought, they also knew of the escape clause and recognized that Leão was the key to stealing the contract. In a ‘Germanic-efficency’ style campaign Krupps used every trick and effort to undermine the Armstrong contract and grab the design of the new Brazilian dreadnought for the German shipyards. They argued that the 14-inch guns was redundant when a Krupp 12-inch shell could obviously penetrate any armor known(?). The Germans pointed out that Brazil would be better off with three ships mounting 12-inch guns, as this would only simplify and reduce the expense of resupply. They undertook a campaign to scale down the Rio de Janeiro, and arm her with Krupps 12-inch guns whilst built in Germany. Krupps even arranged an audience between Leão and the Kaiser. During that meeting the Kaiser assured the Brazilian that the 12-inch Krupp guns were the weapons of choice and that Krupps would be the perfect contractor for the third Brazilian dreadnought.

After taking office in November, Leão delayed a few days the announcement on the third dreadnought. Armstrong’s, Tennyson d’Eyncourt and de Alencar not unnaturally expected a prompt confirmation of the contract and were both surprised and dismayed when Leão announced that the new dreadnought would be, “a powerful unit which will not be built on exaggerated lines such as have not yet stood the test of experience.” He then revealed the Krupp’s design for the dreadnought. On the news reaching Armstrong’s from their agents in Brazil, no one had realized that the weapons system Brazil now sought was the 12-inch gun. Armstrong’s immediately researched a whole series of new designs, eight in total. They were all smaller than the 31,600-ton de Alencar design but mounted guns from 13.5 to 16 inches. Tennyson d’Eyncourt was quickly ordered to Brazil to seize the contract from Krupps and back to Armstrong’s.

D’Eyncourt found that the Kaiser had imposed a strong influence over the Brazilian admiral and that the Krupp’s design of twelve 12-inch guns was now Leao’s goal. D’Eyncourt was unfazed that none of his eight designs would now met with Leao’s new requirements for guns of 12-inch. He managed to persuade Leão to wait a few days and ‘discover’ that Armstrong’s new line of thinking would exceed the Krupp design and be more cost effective. During his conversation with Leão, d’Eyncourt realized that his prospective client regretted that their new dreadnought would be the biggest such vessel in the world, as she would have had with the 31,600-ton Rio design. D’Eyncourt drafted a fresh design overnight that featured not the twelve 12-inch guns of the Krupp design but fourteen 12 inch guns all mounted on centerline, more than any other dreadnought. In addition he add twenty 6-inch guns for the secondary battery and that would set another world record. To achieve this he was required to extend the hulls length, which resulted in his new design offering two additional guns over the Krupp design, plus the longest and heaviest dreadnought in the world. This was achieved at a price several hundred thousands pounds cheaper than that of the earlier Armstrong ‘Rio’ design. The new design was perfect for Leão as Brazil would spend less, but have a ship that would be the world’s greatest in four areas, number of main guns, number of secondary guns, length and displacement. Both men were happy. D’Eyncourt had manage to seize the contract from Krupp and Leão had a record breaking design. D’Eyncourt’s work had one unforeseen consequence for Armstrong’s. Just when he announced that Armstrong’s had regained the Brazilian contract, he received the news that the Royal Navy was looking for a new Director of Naval Construction. D’Eyncourt, who had never been a constructor at the Admiralty, and thought that he would have no chance at this prestigious position. But he applied regardless for the post, and after an interview with the new First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, was given the job. Armstrong’s contract to build the Brazil’s new dreadnought was signed on 3 June 1911, and on the 14th September 1911, the keel was finally laid down.

Here it’s worth pausing for a moment and entering briefly the realm of ‘what if’. ‘What if’ Krupps had signed the contract and the Rio De Janerio was laid down in Germany? The Brazilian economy would still have stumbled and (spoiler alert!) Turkey would still have purchased the vessel. In 1914 with the ship undergoing trials in the Baltic, would Von Tirpitz have, like the British ceased ( sorry damn, another spoiler alert!) the ship? Would Turkey have responded as they did against the British, and would they have joined the Allies? No Dardenelles campaign, no strangle hold on supplies to Imperial Russia, no revolution? All totally speculative but thought provoking, possibly?

Rio de Janeiro was designed with an overall length of 671 ft 6 in (204.7 m), a beam of 89 feet (27 m), and a draught of 29 feet 10 inches (9.1 m) at deep load. She was to displace 27,850 long tons (28,297 t) at load and 30,860 long tons (31,355 t) at deep load. The ship had a metacentric height of 4.9 feet (1.5 m) at deep load. Her turning circle was large, but she manoeuvred well in spite of her length. She was generally considered to be a good gun platform.

When she commissioned into the Royal Navy, Agincourt was considered by her crews to be a comfortable ship and generally well-appointed internally. A basic knowledge of Portuguese was needed to work many of the fittings, as the original instruction plates had not all been replaced, when she was taken over by Great Britain.

She had four Parsons direct-drive steam turbines, each of which powered one shaft. The high pressure ahead and astern turbines powered the wing shafts, and the low-pressure ahead and astern turbines powered the inner shafts. Her three bladed propellers were 9 feet 6 inches (2.9 m) in diameter. The turbines were designed to provide a total of 34,000 shaft horsepower (25,000 kW), but they achieved 40,000+ shp (30,000 kW) during her sea trials, allowing her to exceed her designed speed to reach 22.42 knots. She was able to make headway at 22 knots on full and ideal conditions and her sea keeping was generally regarded as good.

The steam plant comprised of twenty-two Babcock & Wilcox water-tube boilers with an operating pressure of 235 psi. Agincourt bunkers normally carried 1,500 long tons of coal, but if needed she could carry a maximum of 3,200 long tons. In addition she carried 620 long ton’s of fuel oil to be sprayed on the coal to increase its burn rate. At full bunkerage she could steam for 7,000 nautical miles at a speed of 10 knots, Her electric was provided from four steam-driven reciprocating electrical generators.

Agincourt main calibre was the largest number of turrets and main calibre guns ever mounted on a dreadnought and comprised of fourteen BL 12-inch Mk XIII 45-calibre guns in seven twin hydraulically powered turrets. Unofficially they were named after the days of the week, starting from Sunday, going from forward to aft. Officially the turrets were numbered 1 to 7. The guns maximum depression was −3° and an elevation of 13.5°. They fired a 850-pound (386 kg) shell at a muzzle velocity of 2,725 ft/s (831 m/s) and at maximum elevation this gave a range of just over 20,000 yards (11.3 miles (18,000 m)) with an armour-piercing (AP) shells. It’s calculated that 14 x 12inch firing 860lb shells gives a broadside of 12,040lb. But 10 x 13.5 inch, as in Iron Duke, firing the heavier 1,400lb shell returned a broadside of 14,000lb. During the course of war the turrets were modified to allow a 16° elevation, but this only extended the range by 435 yard to 20,435 yards (18,686 m). The rate of fire of the guns was 1.5 rounds per minute. When a full broadside was fired, “the resulting sheet of flame was big enough to create the impression that a battle cruiser had blown up; it was awe inspiring.” Contrary to the common myth, the ship, when firing full broadsides, remained undamaged, and she did not risk breaking herself in half. However a large amount of the ship’s tableware and glassware did shatter when Agincourt fired her first broadside.

On commissioning Agincourt mounted eighteen BL 6-inch Mk XIII 50-calibre guns. Fourteen of these were located in armoured casemates on the upper deck and two each in the fore and aft superstructures, protected by gun shields. Following her modifications for service in the Royal Navy, two further 6-inch were mounted either side of the bridge in pivot mounts protected by gun shields. These guns could depress to −7° and elevated to 13°, later being increased to 15°. The guns had a range of 13,475 yards 7.6 miles (12,322 m)) at 15° when firing a 100-pound (45 kg) shell, with a muzzle velocity of 2,770 ft/s (840 m/s). The rate of fire was on average five to seven rounds per minute, but this would decreased to about three rounds per minute, once the ready ammunition was used up, as the ammunition hoists were to slow or to few to keep the guns fully supplied. About 150 rounds were carried for each gun.

For defence against torpedo boats, there were ten 3-inch (76 mm) 45-calibre quick firing guns. These were mounted within the superstructure on pivot mounts protected by gun shields. Agincourt also carried three 21 inch torpedo tubes (submerged), one to each beam and one mounted in the stern. The water that entered into the tubes when they were fired, was poured onto the torpedo flat to help with reloading the tube and then pumped overboard. This resulted in the crew working in 3 feet of water if a rapid fire was required. Ten torpedoes were carried for the tubes.

At the outbreak of the war eight Mark II torpedoes were earmarked for the Imperial Japanese navy and two Mark IIIs were that were intended for Turkey were allocated to the Agincourt. However her ‘Elswick-type’ submerged tubes required that the torpedoes be shortened from 22 feet 3 inches (6.8m) to 21 3″ feet ( 6.5m) achieved by the removal of a section at the rear of the head. The modified Mark II torpedoes range was 41 knots to 1,000 metres, 41 knots to 2,000 metres, 38 knots to 3,500 metres, 29 knots to 7,000 metres and 25 knots to 10,000 metres.

The Mark III torpedoes were sawn off to 20 feet 8 inches (6.35m) and the ranges were now 41 knots to 1,000 metres, 36 knots to 3,500 metres and 27 knots to 6,000 metres.

After 1916 the stern tube’s torpedoes of 21-in Weymouth Mark III’s was to be ranged for 21-knot running for use by the broadside batteries of Agincourt and Erin.

Each of Agincourt’s main turrets was fitted with an armoured rangefinder mounted onto the turrets roof, and in addition there was an eighth mounted on top of the foretop. By the time of the Battle of Jutland in 1916, Agincourt was probably the only dreadnought within the Grand Fleet not equiped with a Dreyer fire-control table[2]. A fire-control director was equipped sometime after 1916 located under the foretop and one of the turrets was modified to control the entire main armament later in the war. In 1916 to 17 a director for the 6-inch (152 mm) guns was added on each beam, and in 1918 a high-angle rangefinder was added to the spotting top.

The Control Positions for the 12-in guns were located in the fore top, spotting tower (after end of conning tower), No. 2 turret and No. 6 turret. The torpedo director tower was originally marked as an alternative control position, but pre 1916 it was decided to remove this facility function and convert it into a torpedo control position.

The 6-in guns were originally directed from sighting hoods created specifically for this purpose, but the blast of the 12-in made them uninhabitable. By 1915 they’d been relocated to a new control position constructed in the fore lower top.

February,1916 saw Agincourt still without a Dreyer Fire Control Table installed[2], and it possible that she remained deprived of this equipment at the time of Jutland. But by June, 1918, she had been fitted with a Mark I fire control table.

At some stage Agincourt was equipped with two Mechanical Aid-to-Spotter Mark Is, one located on each side of the foretop, keyed off the Evershed rack on the director. As the need for such gear was first recognized in early 1916, its likely that the installations were made post Jutland.[4]

In 1915 the 6-in battery on the upper deck and the 3-in guns were removed from the fire control network in view of their lack of armour protection. It was planned that they would be used solely for anti-submarine defence and not used as part of the centralized 6-in battery in any surface action. From that point the remaining seven 6-in guns on each broadside on the main deck would be formed into 2 groups, group one would comprise of guns 1 to 4 and group two of guns 5 to -7

With such a weight consumed by the turrets and barrels, there remained little scope for extensive armour within the final design. The waterline belt was just 9 inches (229 mm) thick, compared to the twelve inches or more that was standard in other dreadnoughts. It was 365 feet (111.3 m) in length, and from the forward edge of “Monday’s” barbette to the middle of “Friday’s” barbette. Forward of this the belt decreased to six inches for approximately 50 feet (15.2 m) before reducing once more to 4 inches (102 mm) running all the way to the bow. Aft of the midships section the belt reduced to just six inches for a 30 foot (9.1 m) length before thinning finally to four inches (102 mm). The belt stopped short of the stern, terminating at the rear bulkhead. The upper belt extended to the upper deck and was six inches in thickness and ran from “Monday’s” barbette to “Thursday’s” barbette. The armour bulkheads at each end of the ship were angled inwards from the ends of the midships armoured belts to the end barbettes and were three inches in thickness. Four of the ships decks were armoured with the thicknesses varying from between 1 and 2.5 inches (25 to 64 mm).

One of the ships major flaws was the armour of the barbettes. They were 9 inches thick above the upper deck level, but then thinned to 3 inches between the upper and main decks and there was no armour below the main deck, except for “Sunday’s” barbette, which had 3 inches. “Thursday’s” and “Saturday’s” barbettes were 2 inches in thickness. The turret armour was 12 inches to the front, 8 inches (203 mm) on the sides and 10 inches (254 mm) in the rear. The roofs of the turrets were 3 inches thick at the front and 2 inches to the rear. The casemates for the secondary armament were protected by 6 inches of armour and were also defended from raking fire by 6-inch bulkheads.

The main conning tower was armoured by 12 inches of armour on its sides and it had a 4-inch roof. The aft conning tower, (or torpedo control tower), had 9-inch sides and a 3-inch roof. The communications tube running down from either conning tower was 6 inches thick above the upper deck and 2 inches thick below it. The magazines was protected by two armour plates on each side as torpedo bulkheads, the first one an inch thick and the second one and a half inches thick.

Another major weakness was the lack of subdivision, as was standard in most other navies. The Brazilians had preferred to avoid any possible watertight bulkheads, as they might limit the size of the compartments and consequently detract from the crew’s comfort. For example, the officer’s wardroom, which was 85 by 60 feet (25.9 by 18.3 m) in size, was by far larger than any other vessel within the Grand Fleet.

The design overall suffered from a lack of space within the confines of the hull. With so many 12″ turrets, their magazines, overcrowding of the turrets, magazines, and the boilers, space was of a premium. In addition the hulls strength was weakened by the seven deep holes necessary for the turrets support areas. Oscar Parkes, author of British Battleships, wrote about the ship, saying that she was merely a ‘floating magazine with a tremendous volume of fire as her best protection.’

Following the Battle of Jutland 70 long tons (71 t) of high-tensile steel was added to the main deck in an effort to protect the magazines from plunging fire. In 1917 to 1918 two 3-inch (76 mm) anti-aircraft guns were added to the quarterdeck. A 9-foot (2.7 m) rangefinder was added to the searchlight platform on the foremast at the same time. In 1918 a high-angle rangefinder was added to the spotting top.

Her crew compliment on completion was 1115 but by 1917 the number had increased to 1268 men.

The Rio de Janeiro was laid down on the 14th September 1911 by the shipbuilders Armstrong’s, in Newcastle upon Tyne. A labour force was recruited to work on the new contract, as the ship was scheduled for completion in 1913 and to achieve this night-shifts and overtime was required from the workforce. Officially known as the ‘690A’ the sheer scale of her led the the workmen to christen her the “Rio” or the “Big Battleship”. Late 1912 witnessed the first of the 12-inch guns for “Rio” bring transported up to the moors at Ridsdale where the Armstrong proofing range was located. There each gun was throughly tested to the satisfaction of the builders and the Brazilian observers. The launching of “Rio” was scheduled for 22 January 1913 and Armstrong’s were determined to meet that date. They already were constructing a dreadnought for Chile alongside the “Rio” and “Rio’s” slipway was earmarked for the second Chilean dreadnought. The launching was to be a major event and Armstrong’s planned to impress their clients. Representatives from both Chile and Argentina were invited to witness the launch of the Brazil’s ‘super-dreadnought’, as well as representatives of every major and minor power. Present on behalf of Brazil was Mme. Huet de Bacellar, wife of Admiral Huet de Bacellar, the Chief of the Brazilian Naval Commission who christened the ship . The Brazilian Minister was represented by Senhor A. Guerre Duval. Just after 15.00 on the 22nd the hull was christened Rio de Janeiro and launched down into the river Tyne. As she rode in the river awaiting her tow to the fitting out berths, the workforce were busily clearing the slipway for that second Chilean dreadnought.

After the keel-laying ceremony back in 1911 the Brazilian government found itself in an awkward situation. Europe, following the end of the Second Balkan War in August 1913 was under going a recession. This impacted on Brazil’s ability to obtain foreign loans, while at the same time, Brazil’s coffee and rubber exports collapsed. Years earlier the British had smuggled a number of rubber trees out of Brazil and then raised them in the Hot Houses in Kew Gardens. They were then shipped out to a specially prepared plantation in Malaysia, where they flourished. It wasn’t apparant for a number of years but the Brazilian monopoly on rubber had been been destroyed by the British.

There were also reports on new dreadnought construction from overseas implied that the ship would be outclassed on her completion. Payments to Armstrong’s from the Brazilian government continued as normal through June 1913. While Brazilian exports of rubber in 1912 could afford three dreadnoughts, by 1913 they no longer afford even one such vessel. In an effort to improve Brazil’s situation, taxes were lowered on their rubber in a series of moves designed to counter the British impact on the world market. But it failed to regain Brazil its lost share of the market, leaving Brazil unable to afford the new dreadnoughts. De Alencar was once again the Minister of Marine and in October 1913 he announced that the new dreadnought no longer fitted in with the present fleet and would be sold to the highest bidder. He also implied that the other two Brazilian dreadnoughts could be available for sale. In one announcement the South American naval race had come to an end and eight hundred workmen at Armstrong were laid off and now unemployed. During the last few months of 1913 the Rio de Janeiro was moored at the quay but no work was done on her. As time past she developed a deep red color to her hull and was now known as HMS Rust.

But with the door closing on the South American market, a new a door opened in the eastern Mediterranean. From the beginning there were only ever two serious contenders in the purchase of the Rio. Both Greece and Turkey showed interest in purchasing her. Other countries were initially interested in the ship, but with a starting price of around £3,000,000 (£334,741,935@2016) that put the other interested parties out of the bidding. Both Greece and Turkey sought to raise the necessary funds to make the purchase. But Turkey secured a loan of 4 million pounds and on 28th December 1913 bought the Rio de Janeiro for £2,750,000 (£306,846,774@206). On the 29th, Turkey proudly announced that it now possessed the largest battleship in the world, the Sultan Osman I, ex-Rio de Janeiro, which was to be commanded by Raouf Orbay[5]. Both the Sultan Osman I and Reshadieh (HMS Erin) were expected into Constantinople during June 1914, but no later than July.

On 8th January 1914, Captain Rauf Bey arrived in Newcastle with his staff to oversee the final staged of the work on Turkeys purchase. There was new weapon systems had to be installed, plus some facilities in the ship had to be converted to Turkish standards, engines and weapons remained be tested. Rauf Bey was unhappy at the slow pace of the. He was unhappy at the ships weapons and deemed them unsatisfactory. In a letter dated 4th February 1914, he wrote to Istanbul: “The contract for Sultan Osman does not include any clauses requiring the ship to be equipped with anti-zeppelin guns. It would be appropriate for Sultan Osman to be equipped with four pieces of 76 mm guns, which have been tested on Reşadiye at Vickers shipyard. If the Ministry of Navy does not have an objection, it would be advisable to contact the Armstrong shipyard and place an order accordingly with our needs.”

In Constantinople the British naval legation undertook the job of finding 500 crewmen as a nucleus for the Sultan Osman I. Recruits were drafted from fishing villages and coastal towns along with herdsmen from the interior. There was no facilities in Turkey to adequately train them but the legation did the best that they could until May 1914 when the nucleus crew was dispatched to Britain. At this period the Turkish military were clearly divided with the Turkish Army solidly for Germany and the Turkish Navy solidly pro-British. With the impending delivery of the Sultan Osman I and Reshadieh, the public supported the navy.

The Armstrong workforce was re-hired and work resumed on the ship. Following four months of inactivity, the ship was in a poor state. The first few days were required to free her from her rust and dust she’d acquired. In June 1914 the Sultan Osman I finally preceded under her own steam down the Tyne, for her final fitting out. Her tripod masts had to be hinged downward in order to pass under several bridges, but she made the journey without incident. Now it was hoped to see the ship on her trials by the end of June. Her new Captain was assured his command would be completed by 7th July, except for the last two 12-inch guns for the fifth turret, a few 6-inch guns and some gun sights. The workforce speculated as to why the last two 12-inch guns and the gun sights were just sitting there and were not actually being installed. The brass instruction plates were written in Portuguese and a new batch would have to be etched in Turkish, but why was there an additional inscription in English on the back of every Turkish plaque?

On 7th July, 1914 “Sultân Osmân-ı Evve” (Sultan Osman 1) sailed into the North Sea for the first for her trials. By the 8th she was cruising through the English Channel, and by the 9th was off the Devonshire coastline. She briefly entered dry dock in Plymouth in order to check her under water fittings. Having been afloat for 18 months, albeit in the main, moored up, the bottom of the ship was in a poor state and needed cleaning. The ship then departed Plymouth and returned once more to Newcastle, through the English Channel. That night, on route she passed Spithead, which was the venue for a fleet review of the Royal Navy by King George V. The horizon was lit with searchlights from 59 British battleships and 40 miles of British warships, including the Royal yacht Victoria and Albert III. She steamed onwards and 80 miles north of the Tyne undertook her measured mile. For that test she developed 40,000 shp and hit 22.42 knots. The Sultan Osman continued north after the trials, rather than to return to Newcastle. In response to queries from the Turkish officers, the answer was that they were just following the orders from Armstrong’s. On July 18th she anchored at the Firth of the Forth in Scotland. For three days the dreadnought lay anchored here. The reason for the delay was simple, Europe was sliding towards war! Since the dreadnoughts departure from Newcastle on her trials, the political situation had only grown worse.

On 31 July, 1914, Churchill wrote to the King saying that, ‘I have taken the responsibility of forbidding the departure of the Turkish battleship Osman with the Prime Minister’s approval. If war comes she will be called – and should Your Majesty approve – the Agincourt…..’ One benefit for the Royal Navy of having foreign warships constructed in British shipyards, was that they provided an insurance for the Navy. No matter if built at Armstrong’s, Vickers or any of the smaller yards, there was always an inclusion in the contract that allowed the Royal Navy to take over the ship in time of war, with sufficient remuneration to the foreign power whose ship had been seized. The summer of 1914 saw the Royal Navy with a slender lead over the German High Seas fleet, with 24 dreadnoughts and battle cruisers to 17. Since June, Armstrong’s had been requested to slow the finishing process of the Sultan Osman, just as Vickers had been asked to slow the completion of the Reshadieh. But on the 27th July 1914 the Turkish steamer Neshid Pasha anchored in the Tyne with the dreadnoughts Turkish crew on board. The 2nd August was the date Raouf Bey was promised the ship would be turned over to him and the final payment was also made by Turkey on that date. On the 3rd August the final 12-inch gun and the gun sights were installed. But there remained no sign of the ammunition for the guns.

On 31st July, Churchill had sent a letter to both Armstrong’s and Vickers staying that the two dreadnoughts were not to be turned over to the Turkish crew. In view of the strong pro-German sympathy within the Turkish Army, two modern warships in the eastern Mediterranean under the Turkish flag, would pose a threat to the Royal Navy and even worse was the fear that the Turks would immediately sail the ships to Germany. Sometime before noon on 1st August armed guards appeared in both the yards. Rauf Bey asked to run the Turkish flag up on the Sultan Osman with a ceremony on 2nd August at 8 o’clock but on that day an infantry company boarded the Sultan Osman and the Turkish crew were escorted off of the ship and back to the Neshid Pasha where they were kept under lock and key. The Turkish captain was to later write: ‘… We paid the last installment (700.000 Turkish liras). The manufacturer and we agreed on that the ships would be hand over on 2 August 1914. Nevertheless, after we made our payment and half an hour before the ceremony, the British declared that they have requisitioned the ships… Although we have protested, nobody paid attention.”

On 5th August the Ottoman Ambassador to London, Tevfik Paşa, sent a telegram to Istanbul, “When I was informed that the British government has seized two warships of ours and asked our officers to leave, I went to see the under-secretary of the Foreign Office. He said that these measures have been deemed necessary by the Admiralty. When I asked if it is a definitive seizure, he said that it was not an act that obliges the British government to buy the ships, and the government is free to buy them or to return them to us in the future. I tried to question the legitimacy of this arbitrary action, but he didn’t want to discuss and simply repeated what he said before.”

The effect from these seizures on Turkish pride was immediate. The Sultan Osman had been associated with the Turkish population and was a symbol of national pride. There had been a countrywide campaign to raise money to support the purchase of the ship. Throughout Turkey schools, cafes, peasants, fisherman and tradesman had done what they could to contribute money to buy this ship. Peasant women had cut of their hair as a contribution in the battleship drive! It was of no matter what clauses were in the contract, how ‘legal’ British actions were, too every Turk the act of seizure of their two dreadnoughts by the British government was a national humiliation. Over the years imperial Germany had warned the Turkish government about ‘Perfidious Albion’ and finally here was the evidence. The Sultan Osman had been paid for down to the last penny by Turkey, but despite this the ‘rightful crew’ had been removed from their dreadnought at bayonet point, with no offer of recompense. (Turkey was never to receive one penny of compensation). The pro-British feeling within the country was by this one act transformed into resentment or hatred and the pro-German party became dominant. Germany sent the battlecruiser Goeben and light cruiser Breslau, which prior to the war had been stationed in the Mediterranean, to Turkey as a ‘gift’ from the German Kaiser and his government in a shrewd move to recompense Turkey for Churchill actions. The matter that the two ships had to seek sanctuary or face destruction trying to leave the Mediterranean was ‘overlooked’. Through the war Goeben may have flown the Turkish ensign and bore a Turkish name, Sultan Selim, (later Yauvaz), but she was commanded and crewed by Germans. One of her first sorties as the Sultan Selim was to sail into the Black Sea to poke the Russian Bear and bring Turkey into the war on the side of Germany and Austia-Hungry on 29 October 1914.

HMS Agincourt and HMS Erin.

To be commissioned into the Royal Navy, the former Sultan Osman required a few modifications. As built she carried a large and very distinctive flying boat deck spanning the two middle turrets, (no 3 and no 4), on which the ships’ boats were stowed. The Royal Navy felt that with this structure any battle damage could cause it to collapse onto the turrets below, taking them out of action. The boat deck had been christened “Marble Arch’, and was quickly removed. Another more delicate matter was the toilets. The ship had been fitted with Turkish-style ‘squat’ lavatories on her completion. These need to be replaced for the more western ‘seated’ version the crew were familiar with [3]. The anti-torpedo nets and booms were removed, and an addition of two shielded 6-inch guns on either side of the forward superstructure, the removal of her top masts and top gallants, plus the bridge wings were shortened in length. But the ‘Gin-Palace’ wasn’t stripped of all of her luxuries. Even though the Turkish carpets and an amount if the mahogany fittings were removed, enough of the ‘Mauretania luxury’ remained for the Agincourt officer’s quarters to remain the most spacious and luxurious of any ship within the Royal Navy. Her new name, Agincourt, had been allocated to the sixth vessel of the Queen Elizabeth class, which had been authorised under the 1914/15 Naval Estimates. But with the outbreak of the war, her construction had been delayed.

The Admiralty, not unexpectedly, had no plans in place to provide a crew for the Agincourt on short notice. Their solution was to transfer personal “from the highest and lowest echelons of the service….the Royal yachts, and the detention barracks.” Agincourt’s captain (Douglas Romilly Lothian Nicholson), and first officer came from the Royal yacht, HMY Victoria and Albert III, a vessel Sultan Osman I had passed on route from Plymouth to the Tyne at the naval review . The bulk of the new crew were also transferred from the yacht to the Agincourt on 3 August 1914. By this stage the naval reservists had been called up and deployed, so a number of minor criminals who agreed to serve on board, had their sentences cancelled and were transfered from the various naval prisons and detention camps.

Agincourt was finally commissioned on 7th August but would be busy until the 7th September 1914 working up with gunnery and torpedo trials off Scapa or to west of Orkneys. Her modifications hadn’t taken long to complete and on 17 August Agincourt was ordered to leave Newcastle as soon as possible and proceed to the vicinity of Loch Ewe for the gunnery and torpedo practice. By the 20 August she was ready to proceed to sea. Germany were not unnaturally unhappy with the Royal Navy’s ‘instant reinforcements’ of the two Turkish warships. Two German minelayers were ordered to lay a mine field 30 miles north of the Tyne, in an effort to sink or damage the Agincourt as she steamed north to join the Grand Fleet. The two minelayers, Nautilus and Albatross were ordered to lay a minefield off both the Humber and the River Tyne. They sailed in separate groups, and were each covered by a light cruiser and half-flotilla of destroyers. Nautilus’s group, included the cruiser Mainz, and both groups sailed from Helgoland early on the morning of 25 August. Nautilus laid a pair of mine fields that were both 5 nautical miles in length. Albatross’s group included the cruiser Stuttgart, and laid a single mine field that was 11 nautical miles long, but she had laid the field to the northwest of the intended location, owing to heavy fog. On their return journey the groups sank six British fishing vessels.

Early on the morning of 25th August the Agincourt was towed stern first down the Tyne by five tugs and then on reaching the North Sea she turned her bow to the north and commenced her journey to Scapa Flow. She passed by the German minefields without incident and at mid morning she cleared her decks for her first gunnery practice. For the ships safety it was decided against firing the full 14 gun salvo and only half charges were used for the practice. The gunnery practice was unfortunately a failure. None of the main calibre guns fired correctly under the newly installed electrical firing system, and the crews had to revert to the more primitive percussion firing system to get their charges to even fire. The new experimental “churn lever” [6] designed to speed up loading failed to work and a number of the 12-inch rounds fired broke apart in flight. Various causes were discovered, ranging from shells that were from the bottom of magazines and marked “Repaired 1892”, through to the gun chamber design. The latter of which was finally chosen as the reason for the shells’ break up in flight.

Jellicoe records in his book, The Grand Fleet, how the fleet met the ‘new battleship’ Agincourt,’which was bought from Turkey when still in an unfinished state, was met off Noss Head and entered with the Fleet’. Finally early in the morning of 26th August Agincourt took her allocated mooring berth in Scapa Flow, where she joined the 4th Battle Squadron (Dreadnought, Bellerophon, Temeraire and Agincourt) of the Grand Fleet on the 7th September. Over the next few months the ships gunnery officer, Commander Valentine Gibbs, worked to improve his crews skills. Gibbs used every available opportunity to engage the crews in gunnery practice. If unable to go to sea he employed tugs and drifters within Scapa Flow to engage in sub-caliber practice. This involved 2-pdrs inserted into the breaches of the 12-inch guns allowing a full battle training for spotters, gun layers, sighters and the entire gunnery system. Only the loaders got off with a lighter job work load! The practice at sea rarely witnessed more than four guns being fired at once. Agincourt had yet to undergo the test of a full 14-gun salvo, as there were still some fears a full salvo would break her back. But the ships captain and Val Gibbs shared a confidence in their dreadnought, which had by this stage developed a good warlike reputation within the Grand Fleet. While north of Ireland it was finally decided to fire the long awaited full salvo. “The result was shattering and memorable, and justified every fine calculation made by Tennyson d’Eyncourt, Perrett, and the design team of Armstrong’s. There was not a stoved-in bulkhead, not a twisted plate or rib in the vessel. But it was a nerve shattering business that was not to be repeated until the need arose. The broadside of ten big guns in a British battleship was a thunderous business not often indulged in. Many of the Agincourt’s company had never suffered even this impact. With almost half as many guns again the concussion was well-neigh unbearable. No one escaped it, even down in the engine room. The Turkish crockery and glass were smashed in hundreds, and the coal dust found its way out of the bunkers and percolated everywhere. For days afterward the men were still picking it out of their bunks and hammocks and their clothes. Once was enough. But of course none of the other ships believed the story, and the Agincourt retained her reputation that she was the only ship the Germans could never sink because she would do it herself first” [7]. Throughout her career firing a full broadside would produce a hail of rivets inside the hull, but little other damage .

As the months passed, when not sweeping into the North Sea, undergoing exercises or absent on maintenance, the Agincourt and her peers rode at anchor at Scapa Flow. As the time passed it became more difficult to keep the crew motivated. The Agincourt was a spic and span ship, as would be expected given the Royal Yacht source of the core of her crew. The dark cold mornings would witness the crew turned out at 05:40 and would fallen in by 06:00. Then holy-stoning the decks to a gleaming whiteness wound commence. The crews morale was not a bolstered by the crew from the closely moored other former Turkish warship, HMS Erin. No dreadnought coaled, shot, or signaled or drilled more efficiently than the Erin and as long as she excelled in these operational sectors, her captain gave little thought to if she displayed rust and looked down at the heels. The crew of Agincourt would have been scrubbing their decks for over an hour when they would hear from across the Flow the ‘turn-to’ of Erin’s crew. Over the months at Scapa, the crews of the two Turkish ships became archrivals in a series of friendly sporting events.

In November 1914 two battlecruiser HMS Inflexible and Invincible were detached from the First Battle Cruiser Squadron, to assist in the hunt for the German East Asia Squadron following the Battle of Coronel. Beatty requested that Agincourt be attached to his command, a request Jellicoe, rejected having taken into account both her low speed and poor radius of action.

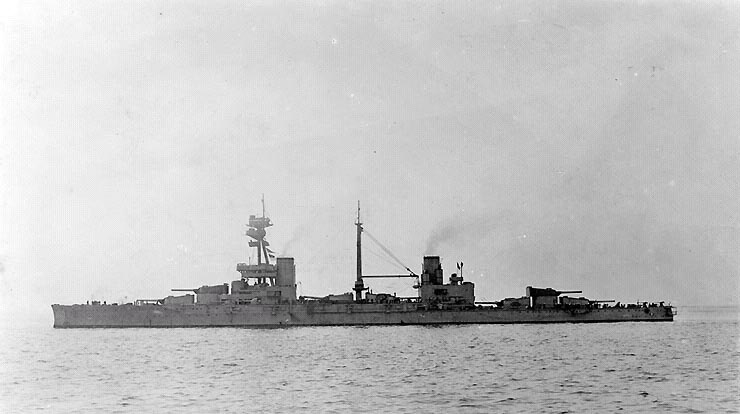

HMS Agincourt (Second from the fron) serving with the fourth battle group in 1915.

In January 1915 Agincourt remained part of the 4th Battle Squadron, alongside Benbow, Bellerophon, Dreadnought, Empress of India, Erin and Temeraire. August of that year saw Agincourt delayed from entering Scapa Flow, following maintenance in Portsmouth, for 36 hours due to fog. She was forced to cruised to the west making repeated attempts to gain access into Scapa.

By January 1916 Agincourt was part of the 1st Battle Squadron with Marlborough, Collingwood, Colossus, Hercules, Neptune, St Vincent and the Vanguard.

By May 1916 Agincourt had been transfered within the 1st Battle Squadron into the Sixth division of the squadron. The Sixth Division at that stage comprised of HMS’s Hercules, Revenge and the flagship, Marlborough, a mixed bag given that each ship was from a different class.

On 31st May 1916 at the battle of Jutland, the Sixth Division formed the starboard most column of the Grand Fleet as it steamed south to rendezvous with the Battlecruiser Fleet. Admiral Jellicoe, C-in-C of the Grand Fleet, retained his squadrons in their cruising formation until 18:15, when he signaled the order for the squadrons to deploy from column into a single line, based on the port division, each ship turning 90° in succession. This redeployment brought the Sixth Division into being the closest ships within the Grand Fleet to the Battle squadrons of the High Seas Fleet. As each British vessel completed its turn to port the German capital ships fired on them, but none were hit.

At 18:24 the official records state that Agincourt opened fire on a ‘German battlecruiser’ with her 12″ guns. The ‘Battlecruiser’ engaged by Agincourt was in most probabuility the German cruiser Wiesbaden. Her 12″ guns were joined shortly after this by her six-inch guns, as German destroyers made torpedo attacks on the British line, in an effort to cover the turn to the south of the High Seas Fleet. Agincourt successfully evaded two torpedoes, but Marlborough was not so fortunate, being struck by one torpedo.

Jellicoe notes that by 18.38 the remaining ships of the 5th Battle Squadron were in station astern of the Agincourt , the last ship of the line.

At 19:15 as the poor visibility cleared Agincourt engaged the German dreadnought, Kaiser, striking her on her upper deck within the hammock stowage area. A second shell followed three minutes later but that shell probably exploded just off the Kaiser’s hull. The brief engagement was drawn to a close by smoke with haze swallowing her target up once more. At 20:00 Marlborough was forced to reduce her speed due to the strain on her bulkheads from her torpedo damage and her division followed suit. Shortly after 20:00, the German battleships engaged the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron. The Markgraf fired her 15 cm guns at the cruisers. During this engagement Markgraf was engaged by Agincourt’s 12-inch guns, which scored a single hit on the German ship at 20:14. But the shell failed to explode and shattered on impact against the 8-inch side armor, causing minimal damage.

In the poor visibility that plagued the battle, the 6th division lost sight of the Grand Fleet during the night, and 23.45 Agincourt sighted a “ship or destroyer”. Agincourt’s captain refrained from opening fire and revealing his ships position as it passed by the badly damaged battlecruiser SMS Seydlitz.

There was a serious concern when Agincourt was completed, that if she was to fire a full broadside she would break in half or sink. But her participation in the Battle of Jutland and the full broadsides she fired on that day finally laid that myth to rest. The broadside was described as “Such a ball of fire that it seemed the ship had blown up.These were full broadsides that the Agincourt was firing. Each time her structure shuddered under the immense recoil impact. But she withstood it all with massive unconcern; and ‘the sheet of flame,’ as one eyewitness in a nearby ship commentated later, ‘was big enough to create the impression that a battle cruiser had blown up; it was awe-inspiring.’ If she survived the battle, ‘The Gin Palace’ could never again be mocked for the supposed weakness of her ostentatious size and length.” [7]. As she cruised towards Scapa a thorough damage survey was conducted. There were no direct hits. The remaining Turkish crockery had been smashed by the concussion of the Agincourt’s own salvoes. There was some splinter damage to the aft superstructure and it was discovered that the cage containing the five pet white ferrets of the ship was broken open by a splinter and that there was no sign of the animals. A few weeks later the ferrets were discovered alive and well, inhabiting a coal bunker where they had fed on a diet of rats. On 2 June 1916 the Gin Palace again anchored at Scapa Flow,

H.M.Doughty, Vice-Admiral Commanding Captain of the first Battle Squadron sent the following account of Agincourt’s battle to the Admiralty:

‘H.M.S. Royal Oak.

Captain: Henry Montagu Doughty

Commander: N. Scott

Engineer Commander: Reginald William Skelton

Lieutenants: Horatio Westmacott – 6-inch Control Officer

Report of Proceedings

No. 171/02.

H.M.S. Agincourt,

10th June 1916.

SIR,

In accordance with your signal, I have the honour to submit the following report on the action of 31st May, as far as H.M.S, “Agincourt” was concerned.

At 6. 0 p.m.The ship’s position was Lat. 57° 7′ N., Long. 5° 41′ E. course 134°. speed, 20 knots.

6.08.Altered course to 122°.

6.17. Altered course to 45°, thereby deploying into line. “Agincourt” now being rear ship of the line.

At 6.12p.m. Our Battle Cruisers and flashes of enemy’s guns came into sight from just on the port bow to the starboard bow, crossing from right to left. Shortly after this, the Fifth Battle Squadron was seen following our Battle Cruiser Squadron and firing at the enemy, but the flashes of these enemy ships’ guns only came into sight through the mist one at a time.

The Lion was noted to have a fire on board, which was apparently put out.

Our Light Cruisers and Destroyers appeared to hang about just in front of the 6th Division, and thus came in for some of the enemy’s projectiles not apparently intended for them.

A clear view of the enemy could not be obtained, but from general opinion the enemy ships first fired on were Battle Cruisers.

6.14.Enemy shots falling near the ship.

6.16.Salvo straddled Hercules while deploying.

6.17.Turned into line after Hercules.

6.18.Marlborough opened fire; but the range was not yet clear of our own ships for “Agincourt.”

6.24.Opened fire on enemy Battle Cruiser; range, 10,000 yards. Target could just be made out, but her number in their line could not be stated with accuracy. Hits had been obtained on this ship when the smoke from our own Armoured Cruisers blotted out the enemy vessels, one of which was very heavily hit.

6.25.Speed by signal—14 knots.

6.32.Opened fire again on same ship. Another hit was observed, but mist made it impossible to be certain of fall of shot.

Our own line of fire was now blocked by our own Destroyers. Fore Control observed a Battle Cruiser, apparently crippled, heading in the opposite direction and flashing FU by searchlight. Fire was then opened on enemy four-funnelled Cruiser, thought to be the Roon.

6.34.Lost sight of enemy.

6.36.Course, 111°.

6.48.Course, 104°.

6.55.Observed Marlborough struck by torpedo or mine on the starboard side. A few minutes after, the periscope of a submarine was seen passing the ship on starboard side. This could be seen from the Control Top and not from the Bridge or Conning-tower.

7.00.Course, 168°; speed, 18 knots.

7.04.Turrets opened fire again on enemy three-funnelled Cruiser. Marlborough was firing at her. She was apparently already disabled and on fire, but was floating when she passed cut of sight.

7.06.Four enemy Battleships, apparently their 5th Division, appeared out of the mist, two of which showed clearly against the mist. Opened fire on one of these: range, 11,000 yards; at least four straddles were obtained and effective hits seen.

7.08.Enemy torpedo just missed astern. It had been reported from aloft, and course was altered. This was probably fired by a submarine.

7.17.Enemy fire straddled ship. Enemy destroyers were now observed approaching from enemy’s lines.

7.18. 6-in. guns opened on them. When five hits had been observed on the first one fire was shifted to another; two hits were observed on her before she was lost in the mist. Enemy destroyers made a smoke screen which hampered the turrets firing during the time enemy ships turned away.

7.35.Track of two torpedoes running parallel observed approaching. Course altered to avoid torpedoes ; passed ahead.

7.41.Submarine reported starboard side ; turned away to avoid.

7.45.Course, 185°; speed, 15 to 17 knots.

7.50.Passed a wreck on port hand.

8.03.Course, 258° ; 17 knots.

8.25. Torpedo track on starboard side ; turned at full speed; torpedo broke surface about 150 yards on starboard bow.

During the night three distinct sets of firing occurred : the first being on starboard quarter; the second two points on quarter; the third right astern.

A ship or Destroyer closed “Agincourt” at high speed during the night, her track very visible. I did not challenge her, so as not to give our Division’s position away. She altered course and steamed away.

2.30.Vice-Admiral shifted his Flag to Revenge.

3.52.Zeppelin in sight. Opened with 6-in. guns and 3-in. anti-aircraft. Apparently no hits were obtained on Zeppelin ; she went away towards the East.

T.N.T. common were used throughout the action.

Rounds fired :—

12-in. guns 144 rounds.

6-in. guns 111

Anti-aircraft guns 7

I have much pleasure in reporting the smooth working of everything on board and the happy alacrity and discipline of all hands. No direct hits were made on “Agincourt,” but several splinters came on board, doing very minor damage.

I have the honour to be,

Sir,

Your obedient Servant.

H. M. DOUGHTY,

The Vice-Admiral Commanding Captain.

First Battle Squadron.

H.M.S. Royal Oak.[8]

In 1917 Agincourt was part of the 1st Battle Squadron with Marlborough, Benbow, Canada, Empress of India, Revenge, Royal Oak and the Royal Sovereign.

By 1918 she had transfered to the 2nd Battle Squadron and served with King George V, Ajax, Centurion, Conqueror, Erin, Orion, Monarch and Thunderer.

Over the thirty months post Jutland,The Grand Fleet was to make a number of sorties but it’s not known by how much Agincourt participated in these. On 23 April 1918, Agincourt and Hercules were stationed at Scapa Flow ready to provide cover for the Scandinavian convoys, then sailing between Norway and Britain. The High Seas Fleet had sailed from its bases in an effort to destroy a convoy, but the reports from German Intelligence were 24 hours off, as both the inbound and outbound convoys were safely in port. Finding nothing on the convoy route, Admiral Scheer ordered the fleet to return to Germany without spotting any British ships.

During 1917, her profile was alerted when her mainmast tripod was modified to that of a pole design. In addition Agincourt received directors for her secondary battery in July 1918. Also in 1918, it was suggested that she should add a 9-foot rangefinder for torpedo control on the fore mast navigating bridge. Since 1915 the a 9-foot instrument in the lower top for the 6-inch guns had been used for torpedo control.

By the wars end Agincourt was part of the 2nd Battle Squadron and was present at the surrender of the High Seas Fleet on 21 November 1918. In March 1919 she entered the reserve fleet at Rosyth and finally decommissioned in April 1921. With the war over the Admiralty sought a foreign buyer for the Agincourt, with an asking price of £1,000,000. Brazil was approached but she eventually turned her down. Plans were put in hand to convert her to oil and add more protection but these were to come to nothing, as no buyers was to be found. It was then decided to use the ship for gunnery testing. She was recommissioned at Rosyth in 1919 as an ‘experimental ship’, and finally as a large depot ship. All the main Gun turrets, except no 1 and 2, were removed but the work on the alterations were stopped in 1921. By 1922 as the result of the terms of the Washington Treaty, she was scheduled for breaking. The ‘Big Ship’ was gone before the end of 1924. No ship in the Grand Fleet had been loved more by her crew and for years afterward the Agincourters mourned her passage.

Today a large model of Sultan Osman Il holds pride of place in the Turkish Naval Museum in Istanbul.

CAPTAINS

Dates of appointment are provided when known.

Captain Douglas R. L. Nicholson, 7 August, 1914 – 10 January, 1916

Captain Henry M. Doughty, 10 January, 1916 – 11 April, 1917

Captain Henry L. Mawbey, 11 April, 1917– 19 February, 1919

Captain R. Cecil Hamilton, 19 February, 1919– 23 June, 1919

Commander Vincent L. Bowring, 25 June, 1919 – 1 April, 1920

NOTES

[1] ‘REVOLT OF THE LASH: Soon after the battleship São Paulo’s arrival in Brazil, a rebellion known as the Revolt of the Lash, or Revolta da Chibata, broke out on the four newest ships in the Brazilian Navy. The initial spark was on the on 21 November 1910 when Afro-Brazilian sailor Marcelino Rodrigues Menezes was brutally flogged 250 times for insubordination. Many of the Afro-Brazilian sailors were sons of former slaves, or were former slaves freed under the Lei Áurea (abolition) but forced to serve in the navy. They had been planning their revolt for some time, and Menezes flogging became the catalyst. But further preparations were needed and the rebellion was delayed until 22 November. The crewmen of Minas Geraes, São Paulo, the twelve-year-old Deodoro, and the new Bahia quickly took their vessels with only the minimum of bloodshed, (two officers on Minas Geraes and one each on São Paulo and Bahia were killed).

The ships were well supplied both with foodstuffs, ammunition, and coal, and the only demand of mutineers, led by João Cândido Felisberto, was the abolition of “slavery as practiced by the Brazilian Navy”. They also objected to the low pay, long hours, inadequate training for sailors, and punishments including ‘bôlo’ (being struck on the hand with a ferrule) and the use of whips or lashes (chibata), which eventually became a symbol of the revolt.

By 23 November, the National Congress begun discussing the possibility of an amnesty for the sailors. Senator Ruy Barbosa, long an opponent of slavery, lent a large amount of support, and the measure unanimously passed the Federal Senate on 24 November. The measure was then sent to the Chamber of Deputies.

Humiliated by the revolt, naval officers and the president of Brazil were staunchly opposed to amnesty, so they quickly began planning to assault the rebel ships. The former believed such an action was necessary to restore the service’s honor. Late on 24 November, the President ordered the naval officers to attack the mutineers. Officers crewed some smaller warships and the cruiser Rio Grande do Sul, Bahia’s sister ship with ten 4.7-inch (119 mm) guns. They planned to attack on the morning of 25 November, when the government expected the mutineers would return to Guanabara Bay. When they did not return and the amnesty measure neared passage in the Chamber of Deputies, the order was rescinded. After the bill passed 125–23 and the president signed it into law, the mutineers stood down on 26 November.

During the revolt, the ships were noted by many observers to be well-handled, despite a previous belief that the Brazilian Navy was incapable of effectively operating the ships even before being split by a rebellion’. (Wikipedia)

[2] The Dreyer tables were based on semi-automated plotting of range cuts and bearings versus time on separate sheets of paper and employing a dumaresq and other appliances to relate these data, guess their derivatives, and compute a continuous range and deflection for use at the guns and/or the director.

For many decades, Dreyer tables have been a scapegoat for poor shooting by the Royal Navy. A technical evaluation suggests that this criticism is misdirected.

[3] A squat toilet (also known as a squatting toilet, Indian toilet, or Turkish toilet) is a toilet used by squatting, rather than sitting. There are several types of squat toilets, but they all consist essentially of toilet pan or bowl at floor level.

Squat toilets are used all over the world, but are particularly common in many Asian and African countries and those with a large proportion of people of Muslim or Hindu faith who also practise anal cleansing with water.

[4] The Mechanical Aid-to-Spotter Mark I was the first Mechanical Aid-to-Spotter deployed by the Royal Navy to better ensure that all members of the fire control staff were in harmony as to which ship their own was targeting. It seems likely that supply commenced in late 1916.

[5] Orbay rose to fame during the second Balkan War in 1913, when Turkey was at war against Montenegro, Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria. As a young commander of the Turkish cruiser Hamidiye, he manage to break through a enemy blockade at the mouth of the Dardenelles to attack enemy shipping in the Aegean Sea.

[6] The turrets Captain of the Gun operated two hand-levers. These were known as “churn levers” by the crews due to their motion around three sides of a square box. Complex mechanical interlocking rods (similar to the type found beneath a railway signal box of the period) were fitted to prevent malfunction.

[7] The Great Dreadnought, 1966, by Richard Hough.

[8] Admiralty (1920). Battle of Jutland 30th May to 1st June 1916: Official Despatches with Appendices. Cmd. 1068. London: His Majesty’s Stationary Office.

SOURCES USED

dreadnoughtproject.org

militaryfactory.com

kbismarck.org

steel naval.com

padresteve.com

History from British Battleships of World War One, 1986, by R.A. Burt

The Great Dreadnought, 1966, by Richard Hough

battleships-cruisers.co.uk

armingallsides.on-the-record.org.uk

nytimes.com

navypedia.org

turkeyswar.com

combinedfleet.com

warshipsresearch.blogspot.co.uk

British Warships 1914-19 by F.JDittmar and J.J.J College

Battleships of world war 1. Antony Preston

The Naval Annual 1913, David and Charles.

The Grand Fleet 1914 – 1916: Its Creation, Development and Work17 Mar 2006

by Viscount Admiral Jellicoe of Scapa and Roger Chesneau

Further Links

Want to follow Navy General Board on Social Media? Check us out on the platforms below!

More Great Articles

The biggest Cruisers of World War II.

Life aboard a US Navy Battleship During the Korean War.

Why were so many Warships Never Built?

The Iowa Class Battleship, A Departure from Traditional Design