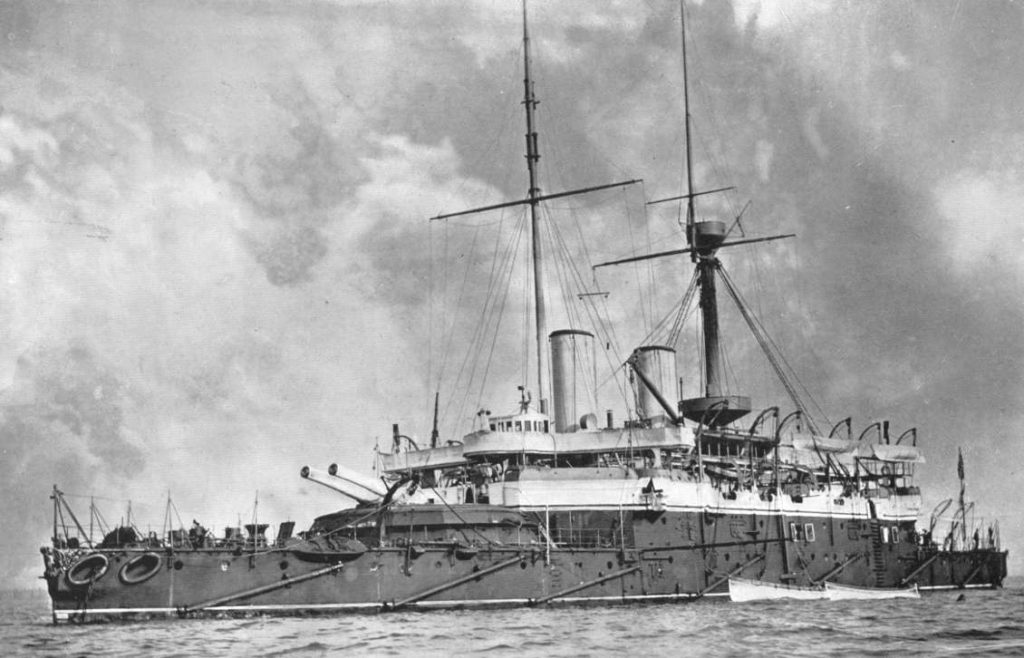

During the early 1880s, Britain laid down six battleships of the Admiral class in several distinct sub-classes, all but one bearing the names of prominent admirals from the Royal Navy’s long history. The prototype was HMS Collingwood, a heavy warship laid down in 1880 and completed seven years later for a cost of £636,996.[1]

Exactly what these ships meant in terms of naval history has been subject to a good deal of debate among historians, a discussion that has evolved over the years. The first idea, presented in the mid-twentieth century by Oscar Parkes, was that the ‘Admirals’ – preceded by Collingwood as a prototype – ended the ‘dark ages’ of Britain’s Victorian-age navy. They were the first ‘class’ of heavy warships in years, and according to Parkes corrected the Royal Navy’s lack of strength.[2] However, this interpretation has been disputed since. The view of the Royal Navy being under-strength was not held by some officials of the day,[3] and the idea of a ‘dark age’ in that sense has since been disproven.[4] The way in which historians have seen the era and its ships, in short, has moved, in part through work done to write doctoral theses.[5]

Could we still consider that the ‘Admirals’ – the first ‘class’ of heavy warships in years – ended a ‘dark age’ of confusion over battleship design? In one study published in 2018 they were called a ‘new type’ of battleship on the back of their combination of features, including the fact that they carried their main armament in barbettes, which was followed in all but a handful of battleships from then on.[6]

The issue is that while – with hindsight – we can see that the ‘Admirals’ were way-points on the path to the classic late-nineteenth century British battleship, that was not obvious at the time. By contrast with later classes, such as the Royal Sovereigns,[7] there was no coherent plan to build multiple ‘Admirals’. Collingwood was initially seen as one-off, and with reason. Technology was in flux. Into this flowed cost. By the early 1880s the limits to military spending included the fact that Britain was in recession, in part triggered by the 1878 collapse of the Bank of Glasgow.[8]

The Admiralty of the 1880s did not know their future; but they did know their past – a period of radical technical change and experimentation. The Royal Navy of the 1860s and 1870s – like most navies of the day – was a fleet of ‘samples’, filled with heavy warships of wildly differing style and capability. Technology was moving so fast that ships were often obsolete before they were completed, and there was intense argument over the best mix. Some ships – notably Dreadnought, laid down in 1870[9] – were held up on the stocks while the Board pondered revisions.[10] Policy was also punctuated by public ‘war scares’ that led to politically-driven panic-buying of ships building in Britain for other nations.

Sail was beating a slow retreat, largely because sail was still thought necessary for reliable blue-water range. The solution – more efficient steam engines and a global network of coaling stations – was in its infancy in the 1870s. That was why the turret ship Inflexible, laid down in February 1874[11] with 16-inch muzzle-loaders in two echeloned midships turrets, on a displacement of 11,985 tons, also carried a full rig of 15,136 square feet of canvas.[12] Sails were effectively useless on a ship of that size and soon removed; but that does not reduce the intent.

A good deal of mythology, partly driven by the discredited ‘dark age’ idea, shrouds Collingwood’s origin. This has always been put down to an 1879 French plan to build up to four new battleships, two first-class and two second-class, with heavy guns and compound armour. This last was another innovation of the 1870s, made by pouring a steel layer atop an iron backing plate.[13] It offered resistance greater than wrought iron alone.[14]

It might seem that Collingwood and then the ‘Admirals’ were the response to the French initiative, but this is not borne out by the construction programme the Admiralty requested for 1880-81. This originally authorised three new-build ‘ironclads’, the blanket government term for capital ships of the day. The word ‘battleship’ was informally in use, inherited from the days of sail; but it had yet to be adopted as an official classification. A change of government in April 1880 then changed the Board of Admiralty, who cancelled two of the ‘ironclads’ and instead decided to accelerate work on ships under construction as a way of bolstering the fleet. In short, the total either completed or under construction by then were thought ample to meet the new French programme. Just one ‘ironclad’ remained in the programme, to be built at Pembroke dockyard.[15] This became Collingwood.

What to build was left up to Barnaby. He had concluded that ships needed to be smaller if they were to be built in number. To keep the fire-power up meant reducing the total weight of armament, which meant mounting it in open barbettes rather than heavy turrets. Barnaby therefore proposed a small barbette ship – following the French Caiman[16] – and handed it for development to his associate, William White.[17] What emerged was heavier at around 9,200 tons,[18] much the same as the preceding Colossus class.[19] However, the point is that Barnaby’s idea – which gave the ship its shape – was driven by the politics of Royal Navy funding.

Was Collingwood a ‘new’ type of battleship? Certainly, but arguably no more so than any other of the ships of her day. Despite the French influence, the general layout otherwise derived from the Dreadnought of 1870.[20] Even the breech-loading main armament – Mk Vw 25-calibre 12-inch guns[21] – was not new. This had been introduced in the preceding Colossus class, as had all-steel general construction. And Collingwood was designed around ‘citadel’ armour, a concept introduced with the Inflexible. This was intended to protect a central ‘raft’ and allow the ship to remain afloat even if her unarmoured ends were flooded.[22] Like her immediate predecessors, Collingwood was also designed from the outset to be ‘mastless’ – a period term meaning that she did not use sails for propulsion.

In other ways, Collingwood innovated. She was only the second British ship to have barbettes, and the first to carry her entire main armament in them.[23] Displacement limits meant she was low-freeboard, but the barbettes could be raised above weather deck level, making them workable in heavy weather.[24] She also introduced a significant secondary battery of six 6-inch/26 calibre guns,[25] intended to wreck unarmoured elements of enemy battleships in fleet action. And she was the first British ship with forced draught, estimated to give her a top speed of over 16 knots.

The point is that this mix of existing and new technologies was also true of many vessels of the period. All, one way or another, introduced new technologies as they emerged, and all offered new combinations of available systems. The issue – particularly given the pace of technical change – was that nobody knew which one would set the trend. Again, with hindsight, we know that the combination adopted for Collingwood hit the mark. But this was not obvious at the time. The open barbettes, for example, drew criticism because they left the gun-crews partially exposed to enemy fire in ways that turrets did not. Barnaby’s rival Edward Reed also dismissed the ‘citadel’ armour scheme. And both arguments had their points at the time.

The story of how five further ships were then built to much the same theme is considerably more interesting than a simple plan to build sister ships. It is a story filled with the politics of the day – personal and national – including bitter rivalries, struggles for funding, and the relentless march of technology. We will explore this in the next article.

Meanwhile, for the other end of Britain’s battleship evolution, check out my short book Britain’s Last Battleships.

Copyright

© Matthew Wright 2019

[1] Roger Parkinson, The Late Victorian Navy: the pre-dreadnought era and the origins of the First World War, Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2008, p. 206.

[2] John Francis Beeler, British Naval Policy in the Gladstone-Disraeli Era, 1866-1880, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1997, pp. 191, 202-205.

[3] Ibid, p. 208.

[4] See, e.g. ibid, pp. 208-209.

[5] Steven Gray, ‘Black Diamonds: Coal, the Royal Navy and British Imperial Coaling Stations circa 1870-1914, PhD Thesis, University of Warwick, March 2014, pp. 33-35.

[6] Norman Friedman, British Battleships of the Victorian Era, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2018, p. 181.

[7] Detailed in R. A. Burt, British Battleships 1889-1904, Seaforth, Barnsley, 1988, new edition 2013, pp. 68-100.

[8] Michael Collins, ‘The Banking Crisis of 1878’, Economic History Review, 2nd Series, Vol XLII, No. 4, pp. 504-527.

[9] Tony Gibbons, The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers, Lansdowne Press, London 1983, p. 94.

[10] The Captain disaster rendered low-freeboard turret ships temporarily suspect, even if mastless (ie: not sail-rigged). See Burt, p. 9; also Friedman, p. 131.

[11] Gibbons, p. 102; note that Gibbons cites displacement as 10,300 tons light, 11,880 full load; and (p. 103), 18,500 square feet of canvas.

[12] Friedman, pp. 156, 380;

[13] https://eugeneleeslover.com/ARMOR-CHAPTER-XII-A.html, accessed 14 July 2019.

[14] Friedman, p. 183.

[15] Ibid, p. 182.

[16] Roger Chesneau and Eugene M. Kolesnik (eds), Conway’s All The World’s Fighting Ships 1860-1905, Conway Maritime Press, London 1979, p. 29.

[17] Friedman, p. 183.

[18] Friedman, p. 381; but see also Gibbons, p. 110.

[19] Friedman, p. 380.

[20] Ibid, p. 131.

[21] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_12-25_mk3.php, accessed 14 July 2019.

[22] This went out of favour in the face of the risks posed by medium-calibre guns. The US Navy re-introduced the principles shortly before the First World War.

[23] The earlier HMS Temeraire, also designed by Barnaby, carried her armament in barbettes and a central battery, see Gibbons, p. 89.

[24] Chesneau and Kolesnik (eds), p. 29.

[25] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_6-26_mk1.php, accessed 29 July 2019.