by Matthew Wright

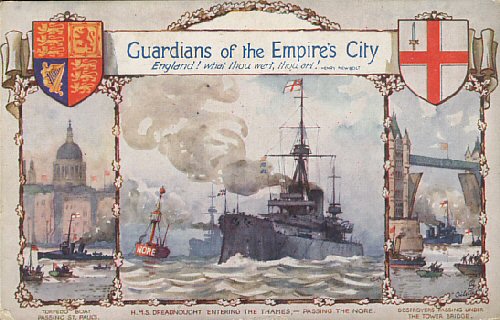

One of the received truths of naval history is the idea that HMS Dreadnought of 1905-06 was a game-changer, the ship that divided naval construction between ‘before’ and ‘after’.[1] And in many respects, that is true. She was the first all-big-gun battleship to take to the water, the first battleship with turbine propulsion, and her design speed was a significant jump over any earlier battleship. Other all-big-gun ships were on the drawing board elsewhere at the time, but Dreadnought’s combination of new technologies and speed was unique. Thanks to Britain’s pre-eminent status as a global naval power, and the enthusiastic propaganda of the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Fisher, she gave her name to that type of vessel.

The idea that Fisher saw Dreadnought as integral to his overall naval revolution of the day became axiomatic. The concept was one of the general themes of US historian Arthur Marder (1910-1980). In his Harvard doctoral thesis of 1936, published in 1940, Marder had asked whether Dreadnought was Fisher’s ‘blunder’, or ‘genius’.[2] He answered that question in his massive five-volume follow-up, the magisterial From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow. This was a master-work by any measure: a display of meticulous research, analysis and dedication to the field. To Marder, Fisher’s general naval revolution had prepared the Royal Navy for its challenge in the First World War. And – as far as Marder was concerned – Fisher saw Dreadnought as a key element.

History, of course, is an ongoing discussion. In part that is because we can only catch glimpses of the true breadth and richness of the past through what has been captured in available records. The gaps in what can be known leave room for discussion, as we seek to understand what the past meant. But in any case, new data can emerge, casting past events in fresh light and offering new meanings. Beyond that, society changes with time. That change provides new perspectives of the past; and so new generations of historians develop new questions to ask. That same process also influences the methods historians use to discover the place of historical events and trends – why they occurred, and what they meant. Since Marder’s time, for instance, analytical methodology across the humanities in general has been influenced by social ‘scientific’ thinking, pioneered by the philosopher Karl Popper among others.[3]

The shift in historical thinking – which affected every part of the field from the mid-late twentieth century – was dubbed ‘revisionism’ and questioned older ideas. Naval history was no exception, and from the 1970s through to the end of the twentieth century, academic historians such as Charles Fairbanks, Jon Tetsuro Sumida, Nicholas Lambert and Christopher Bell began questioning the conclusions of the prior generation of historians of the Royal Navy during its ‘dreadnought’ era.[4]

To question old approaches is, of itself, always useful. History, after all, is not merely a series of questions to be answered. It is also a series of questions whose answers must be tested. History at this level is also not an effort to discover a single objective truth – for even if past societies and events can be reduced to such simplistic levels, discovering such is going to be elusive when even the best data – when set against the wide realities of the past – is only partial; or if primary sources vary. For these reasons history is, instead, always a discussion.[5]

According to the ‘revisionist’ historical argument, Marder’s methodologies were limited, and while meticulous, as a researcher he didn’t have access to the documents such as cabinet papers and those produced by the Committee of Imperial Defence, because these were withheld under the 50-year rule: the last relating to the First World War were not released until 1968. He was given access to some closed Admiralty files in 1938, but not the full range. Later, after the war, the Admiralty actively tried to block him seeing more on the basis that he was ‘foreign’. This said, there has been suggestion that Marder might have seen more Admiralty files than have since been preserved in the Public Records Office, because the Admiralty regularly destroyed files.[6]

Much pivoted, of course, around Fisher – a prolific letter-writer with whom Marder was closely familiar. During the 1950s Marder edited and published three volumes of Fisher’s personal papers.[7] However, these works did not include some key documents.[8] In part this is because Fisher’s papers were not fully indexed until nearly a decade after Marder’s last volume of letters was published. Late in 1967, the New Zealand historian Ruddock Mackay (1922-2019) and a full-time assistant, Hazel Edbury, began the enormous job of sorting and indexing the available collection of some 6000 items, ranging from single documents to complex volumes. Mackay was available only part-time. The task took them twelve months.[9]

Later, Mackay penned what remains one of the best biographies of the Admiral ever written: an insightful analysis based on material that had never been explored in that depth before.[10] In a sign of both the relatively small scale of the academic naval field of the day, and the close links between those in it, his book Fisher of Kilverstone and an earlier biography of Admiral Hawke were submitted for a Doctor of Letters from St Andrews University, refereed by Marder and by Stephen Roskill – a former RN officer and the Royal Navy’s official historian.[11]

All this new information, coupled with the general mood of re-thinking older ideas, shortly led to a swing against Marder’s conclusions in the academy – and a re-think of the idea that HMS Dreadnought had been Fisher’s intended hardware revolution. Perhaps, various historians proposed, Fisher had another concept in mind. Perhaps what happened wasn’t a ‘dreadnought revolution’ at all, but a failed ‘battlecruiser revolution’ that Fisher couldn’t get off the ground? And what of the submarine, another new technology that had captured Fisher’s imagination?

The problem for historians was that – apart from the fact that written material can’t capture the subtleties of thought or the minutiae of private conversations now lost to the past, Fisher was remarkably coy when it came to revealing his true motives. This was intentional. ‘The one great rule in life is NEVER EXPLAIN’, he thundered in 1911 to the journalist Arnold White.[12] And he didn’t, particularly.

So what was going on? We shall continue this story in the next article.

Meanwhile, for more on Fisher’s influence on the battlecruiser, check out my book The Battlecruiser New Zealand: A Gift to Empire (USNI Press/Seaforth). Buy now from Amazon.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2021

[1] There are many examples, but see e.g. For example, David K. Brown, ‘British Warship Design Methods 1860-1905’, Warship International Vol. 32, No. 1 (1995), pp. 59-82; Roger Chesneau and Eugene M Kolesnik, Conway’s All The World’s Warships 1860-1905, Conway Maritime Press, London 1979.

[2] Arthur Marder, The Anatomy of British Sea Power, a history of British Naval Policy in the Pre-Dreadnought Era, 1880-1905, A. A. Knopf, New York, 1940, p. 513.

[3] Popper, a refugee of 1930s Austria, taught at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand; then moved to Oxford. I studied as a post-graduate under one of Popper’s own students, Peter Munz.

[4] For summary see Angus Ross, ‘HMS Dreadnought (1906) – a naval revolution misinterpreted or mishandled?’, Le Marin du Nord, Vol. 20, No. 20, 2010.

[5] See, e.g. Nicholas A. Lambert, ‘On Standards: A reply to Christopher Bell’, War in History

Vol. 19, No. 2 (April 2012).

[6] Matthew S. Seligman, ‘A Great American Scholar of the Royal Navy? The Disputed Legacy of Arthur Marder Revisited’, The International History Review, Vol, 38, No. 5, 2016, pp. 1040-1054.

[7] See, e.g. Arthur Marder (ed), Fear God and Dread Nought: the Correspondence of Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher of Kilverstone, Vol, III, Jonathan Cape, London 1959.

[8] Noted, e.g. in Christopher M. Buckley, ‘Forging the shaft of the spear of victory: the creation and evolution of the Home Fleet in the pre-war era, 1900-1914, PhD thesis, University of Salford, June 2013, p. 173.

[9] Ruddock F. Mackay, Fisher of Kilverstone, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1973, p. vi.

[10] For comparison see. e.g. Richard Hough, Admiral of the Fleet: the life of John Fisher, Macmillan, New York 1969. Jan Morris, Fisher’s Face, Penguin, London 1996, was comparable calibre to Mackay but had different purpose.

[11] John Brooks, ‘Ruddock Mackay (obit)’, The Mariner’s Mirror, Vol, 105, No,2, 2019. The Lit.D is not an ‘honorary’ degree but an actual doctoral degree – recognition, by doctorate, of the scholarship shown in a body of work by an individual already qualified in academia.

[12] In Arthur Marder (ed), Fear God and Dread Nought, Vol. II, Jonathan Cape, London 1956, pp. 388-89.

Recent Comments