The mastless steel battleship essentially emerged from the engineering chaos of mid-nineteenth century technological change and evolved – fairly steadily, but with occasional jumps – through to the end of the classic battleship era after the Second World War. One common feature throughout was a secondary armament; small, quicker-firing weapons, often of multiple calibres. There was a surprising similarity between the secondary armaments of the first ships to carry them in any measure – which emerged essentially from the late 1870s – and those of the late 1930s: a mix of small-to-medium calibre guns, backed by machine guns.

But the purposes of that armament in the nineteenth century was very different from that three generations later. And between times, secondary armament went through some remarkable metamorphoses, also on the back of changing technology and tactical need. Not every nation took the exact same path; as late as the Second World War, for example, the Germans carried different weapons for anti-surface and heavy anti-aircraft work at a time when other nations had switched to dual purpose weaponry.

Broadly, though, battleships were given secondary armament to meet three general purposes, which themselves evolved during the period from the 1870s to the mid-twentieth century, when the battleship era ended in its ‘classic’ form. The purposes were initially anti-torpedo boat armament, then both anti-torpedo and anti-ship armament; and finally dual-purpose/anti-aircraft armament. This article covers the first two, up to the end of the First World War.

HMS Dreadnought, from Brassey’s Naval Annual, 1888. Her original armament of just four big guns is clear: later, though, she was given lighter weapons. Public domain.

Secondary armament emerged for several reasons. Ships such as the British Dreadnought of 1879 – designed nine years earlier – at first carried just four weapons: muzzle-loading 12.5-inch guns in turrets.[1] The only other weaponry aboard were the usual small-arms deployed by the sailors and marines, both in case of boarding, or for potential work ashore.

That was changing even as Dreadnought was being built. The big threat of the 1870s and beyond was the torpedo. These began as explosive devices on long spars, driven into an enemy ship by a brave crew in a small but fast vessel. However, once the self-propelled ‘automobile’ torpedo had matured, the threat of small, cheap ‘torpedo boats’ being able to sink large and expensive battleships was very real. Heavy battleship guns were too unwieldy to engage torpedo boats of only about 300 tons displacement, and for a while the days of battleships seemed numbered. The Russians and the French picked the idea up with enthusiasm, seeing it as a way of beating the British very cheaply.

Torpedo boats attacking the Chilean central battery ship Almirante Cochrane, 1891, during the Chilean Civil War. Public domain.

The British came up with three answers: larger torpedo boats designed to destroy the first type – soon known as ‘destroyers’ – passive defence in the form of heavy steel nets the battleship could deploy; and a more active approach involving quicker-firing light guns. These last were emerging aboard heavy warships by the 1880s in several forms, typically firing 6- or 12-pound shells, backed by heavy machine guns such as the Nordenfeldt ‘organ’ style machine gun, designed by Helge Palmcrantz in 1873. One of the first British battleships to carry such weapons was the Inflexible, completed in 1882, whose 20-pounder saluting guns suddenly gained a new role.[2]

A four-barreled Nordenfeldt machine gun of the 1880s. Public domain.

The first British battleships equipped with 6-inch guns as part of their armament were the Ajax and Agamemnon, completed in 1883.[3] These weapons were not quick-firers: they were slower-firing Mk II breech-loaders made at the Royal Gun Factory in Woolwich.[4] That meant they were not well-suited to engage fast-moving torpedo boats. But they were capable of engaging other battleships. Later battleships, both British and those of other nations, added more guns of this general size, which took its place alongside lighter anti-torpedo boat armament.

HMS Victoria (1890) firing her main armament. She carried just two 16.25-inch guns in a turret forward; but her battery of a dozen 6-inch guns, carried further aft – backed by a single 10-inch – was equally as important when engaging battleships at the time. Public domain.

These weapons also gained lethality with the advent of ‘quick-firing’ mechanisms, allowing them to pump out multiple rounds a minute. That steadily improved as time went on. The French 138.6 mm (5.46”) quick-firers, first produced in 1884 had rate of fire of up to four rounds a minute.[5] The British then developed a 6”/40-calibre quick-firer, introduced in 1892, which had a rate of fire of up to seven rounds a minute.[6] And by the turn of the century the United States Navy had a 6-inch gun able to fire up to 6 rounds a minute.[7]

These guns were also considered likely to be decisive. Battle ranges were expected to be anywhere from about 3,000 to 6,000 yards, or thereabouts. Even a 6-inch shell could penetrate thinner armour at that range, and the shells could devastate unarmoured areas. The potential for what in modern terms might be called a ‘mission kill’ was significant, to the point where the quick-firer armament was sometimes considered the true main armament of a battleship.

Just to give that perspective, the British Director of Naval Construction of the 1890s, Sir William White, openly considered such weapons to be a greater danger than heavy guns.[8] It was against this threat, and not heavy fire, that White developed the armour scheme of HMS Renown, a second-class battleship he designed in 1892. This set the pattern for all his subsequent heavy ships. Larger areas of slightly thinner armour offered fairly good protection over wide part of the hull against the ‘smashing’ effect of 6-inch or similar fire. It was also adequate against most heavy shells of the 1890s; but as a hedge against better armour-piercing shells emerging, White also introduced a sloped armoured deck, designed to catch anything that came through the main belt.[9]

The quick-firing 6-inch guns, or similar calibres, fitted to most nations’ battleships by the 1890s had a potential anti-torpedo boat role, but they were really too heavy for that kind of work; smaller weapons were retained for the purpose. Meanwhile, the size of ships continued to grow and with it the weaponry they could carry. By the late 1890s, battleships – led by the United States Navy – were being fitted with an ‘intermediate’ battery of anything from 7.5- to 9.2-inch calibre, designed to bolster their heavy fire-power.

That introduced fire-control complications at a time of increasing battle range, which simultaneously reduced the effectiveness of 5.5-inch or 6-inch secondary guns. The outcome was that by 1903-04, naval designers from the United States to Japan were working on warships that focused on big guns only. That did not eliminate the need for secondary armament against torpedo boats, however, and this was where arguments brewed, certainly in Britain. By this time the torpedo boat/torpedo boat destroyer arms race, coupled with the need for such ships to have ocean-going characteristics, had led to a sharp rise in scale. Lighter guns such as the 3-inch/50 calibre guns the US Navy was using for the purpose,[10] or the similar 12-pounders (3-inch guns) the British used, were becoming too light to deal with them.

Nonetheless, the first United States dreadnoughts, the South Carolina class, supplemented their all-big-gun armament only with 3-inch guns; and the British – pushed by Admiral Sir John Fisher – did much the same with their Dreadnought of 1906, which carried 27 12-pounders. So did the Italians: their first dreadnought, the Dante Alighieri, completed in 1913, carried a dual secondary armament of 3- and 4.7-inch guns. The stand-outs were the Germans; their first dreadnoughts, the Nassau class,[11] deployed 15-cm (5.9-inch) SK L/45 weapons in addition to their big-gun main armament.[12] However, this was less to do with anti-destroyer work than the fact that the Germans expected to fight relatively short-range battles in the North Sea, where the 6-inch weapons were also effective against heavier ships, including unarmoured parts of any battleship.

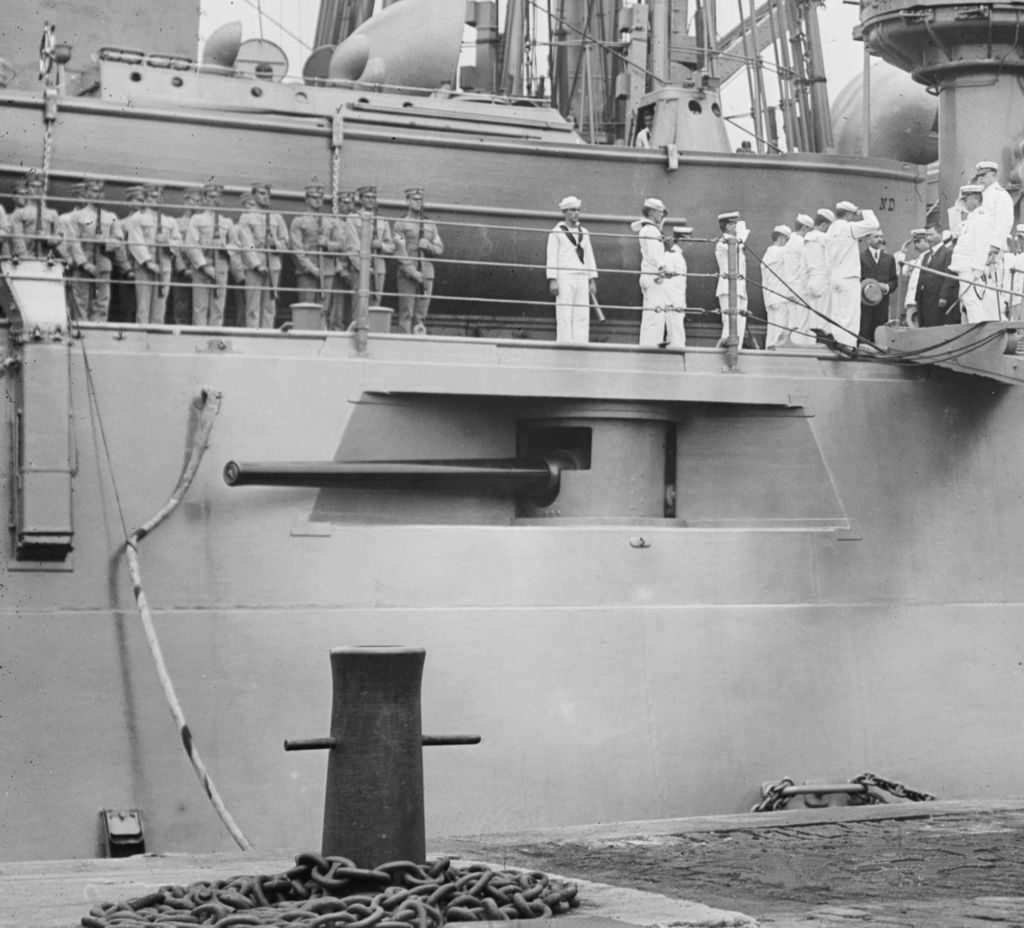

USS North Dakota, a Delaware class dreadnought of the US Navy, with the 5-inch armament visible amidships in casemates. Public domain, via Wikipedia.

It did not take long, however, for the other major nations to follow suit – not so much to engage battleships, old-style, but because of the rising scale of destroyers. The US Navy’s second class of dreadnoughts, the Delawares, increased the secondary armament to 5-inch/50 calibre weapons.[13] Britain was slower, thanks to Fisher; he seems to have felt such weapons disturbed the purity of his concepts and only grudgingly allowed a rise to 4-inch secondary guns. These were still relatively marginal for anti-destroyer work, but Fisher was intransigent.

As a result, it was not until 1911 – the year after Fisher left office as First Sea Lord – that the British were able to reintroduce the 6-inch gun as secondary armament. The Iron Duke class, designed that year, were the first British battleships to mount such weapons since the pre-dreadnought era: but they were for very different purpose than the pre-dreadnought armament. The 13.5-inch main guns of such ships could fire to the horizon, and battle ranges were expected to be at least 10-12,000 yards or more – underscoring the extent to which the 6-inch gun had lost its role as an anti-battleship weapon. But it remained effective against any lighter vessels – particularly destroyers – that might venture within range.

For more on matters naval, check out my book Britain’s Last Battleships. Available now from Amazon.

Copyright

© Matthew Wright 2019

[1] Tony Gibbons, The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers, Lansdowne Press, London, 1983, p. 94.

[2] Norman Friedman, British Battleships of the Victorian Era, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland 2018, p. 156.

[3] Gibbons, p. 105.

[4] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_6-26_mk1.php, accessed 10 July 2019.

[5] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNFR_55-45_m1891.php, accessed 9 July 2019.

[6] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_6-40_mk1.php, accessed 9 July 2019.

[7] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_6-50_mk8.php, accessed 9 July 2019.

[8] Friedman, British Battleships of the Victorian Era, p. 251.

[9] Ibid, p. 252.

[10] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_3-50_mk2.php, accessed 10 July 2019.

[11] Gibbons, pp. 174-175.

[12] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNGER_59-45_skc16.php, accessed 10 July 2019.

[13] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_5-50_mk5.php, accessed 10 July 2019.