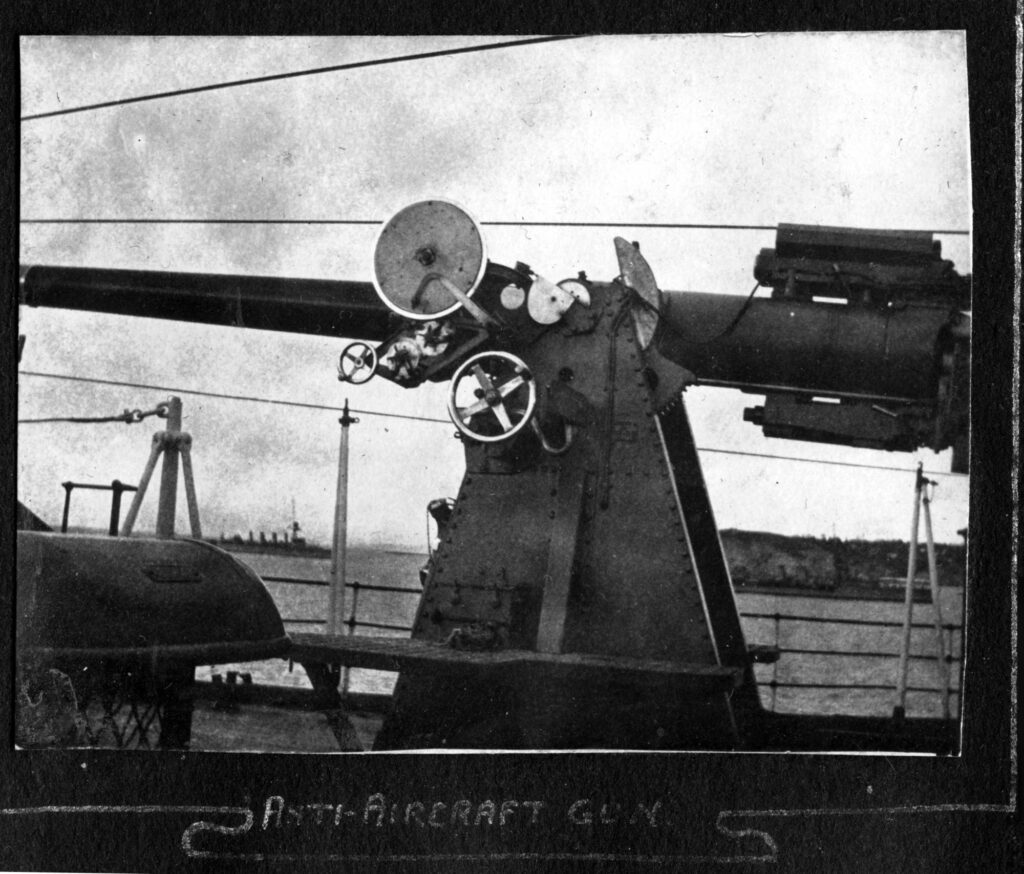

It is not often that previously unknown photos of HMS Hood are discovered. A set were found recently in a New Zealand archive, and are reproduced here for the first time on a naval website. The quality is typical of the day: the slightly blurred imagery typical of the Box Brownie cameras owned by a fair number of households during the period, captured on 12-frame celluloid roll film and, in British territories, typically printed on Velox-brand photographic paper.

Photography was not the cheapest hobby – yet, when HMS Hood and her consorts arrived at various ports around the world as part of a 1924 tour, the public flocked to see her, with their cameras. The pictures typically made their way to family albums.

The historical value of the newly discovered images is the social context, made clear by the hand-drawn captions that went with them. The album described Hood as ‘the largest battleship in the world!’ and described her main armament as ‘16-inch guns’. Neither was correct – she was, of course, officially classified as a battle cruiser, which in British usage of the day was always two words,[1] and she was armed with 15-inch Mk I guns in Mk II mountings.[2]

Such captions are nonetheless valid historical data in other ways, revealing a good deal about how the public perceived Hood – in short, showing what the ship symbolized to them, emotionally. This had nothing to do with engineering detail and everything to do with feeling. Any of the superlatives associated with heavy warships sufficed to convey that image. Indeed, even the New Zealand media of the day referred to Hood as a ‘battleship’.[3]

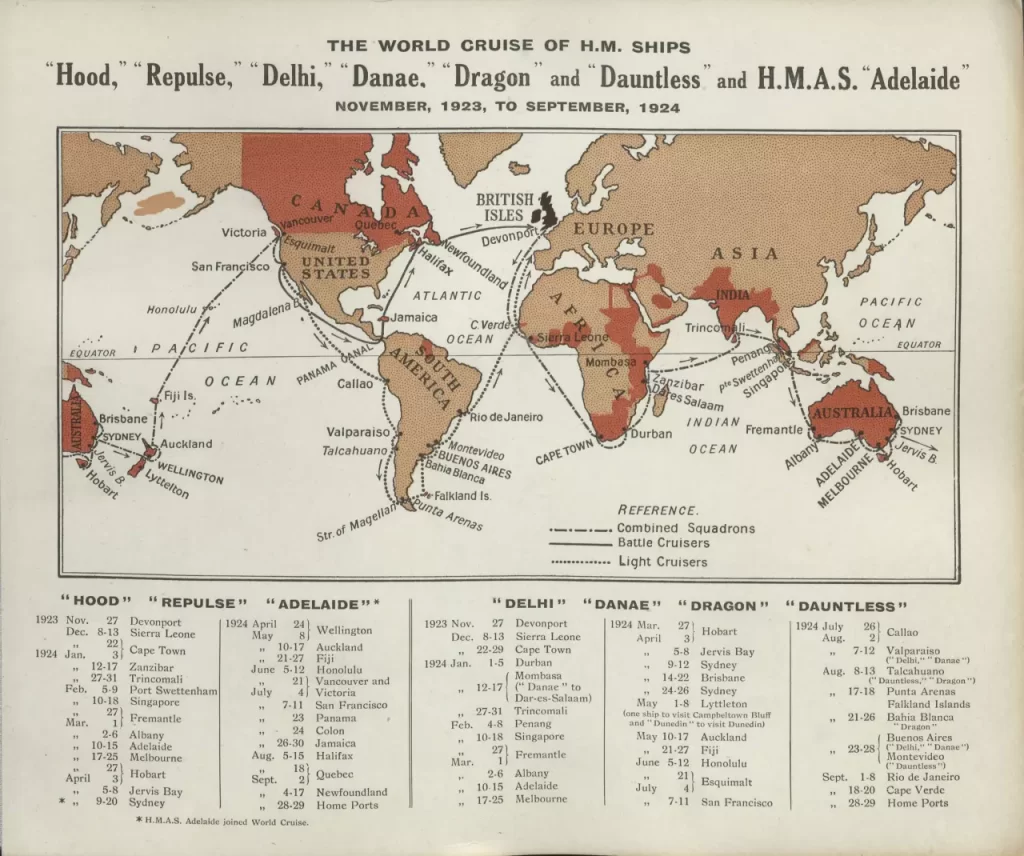

This social place is historically important – for that was largely the reason why these photographs exist at all. In November 1923 the British dispatched a Special Service Squadron on a ten-month world tour. The force comprised two modern battlecruisers – HMS Hood and HMS Repulse – and five light cruisers, including HMS Dunedin, which was on a delivery voyage to the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy. She was left in New Zealand, and her place was taken for the last half of the cruise by HMAS Adelaide, which joined the squadron in Sydney.

The inspiration came from a 1913 world tour by the battlecruiser HMS New Zealand, which is often portrayed solely as a visit to its donor country but in fact was designed to represent British interests across a wide swathe of the globe, with emphasis on South American ties, which were important to Britain.[4] The tour of HMS New Zealand was a great success, and the route of the Special Service Squadron a decade or so later traced the same path, including the South American leg, which in 1924 was conducted by the light cruisers alone. This leg was nonetheless important: up to 1914 the major South American nations of the day were closely tied to Britain due partly to the arms industry, in what has been called an ‘informal’ British Empire. This crumbled in wake of the re-alignments of power that followed the First World War.[5] From this perspective, then, the Special Service Squadron played an important political role on multiple levels.

The British government certainly had high hopes for the political effect. Post-war politics had been reshaped by the Washington Conference of 1921-22. This was about more than just arms limitation: the main focus was a substantial realignment of European power balances in Asia, notably cancelling the Anglo-Japanese Alliance.[6] Amidst this churn the need for Britain to show strength seemed clear, and planning for a global naval tour began in early 1923. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Leopold Amery, saw benefits at multiple levels. It was going to show the flag to a large part of the Empire, sow goodwill largely via sports contacts and social events, demonstrate the ability of the Royal Navy to project force over global distances, and allow the Royal Navy to exercise with the local naval forces being built up by the Dominions.

Part of the intended effect of the tour within the Empire was overtaken by the Imperial Conference of 1923. Here it became clear that the main self-governing Dominions – South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and Canada – were looking for a more independent role in world affairs. The cruise nevertheless went ahead under Vice-Admiral Sir Frederick Field, aboard HMS Hood. The choice of Hood to lead the squadron was no accident: she was the world’s largest warship of the day – and, thanks to the constraints of the Five Power Treaty (‘Washington Treaty’) signed in February 1922, likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. As such she symbolized the might of Empire in ways no other British warship could. And that panned out: the ‘Mighty ‘Ood’, as they called her,[7] was the star attraction during the 38,152 mile cruise: the public flocked to see her, and around three quarters of a million people flocked aboard during open days and ‘at home’ social events aboard the warships.

The reception was particularly warm in Australia and New Zealand, made clear by visitor numbers: of the approximately 1.9 million people who came aboard the squadron during its tour, 1.42 million were from New Zealand or Australia.

The squadron toured New Zealand during the first weeks of May 1924, and it is here that the story of these photographs begins. On 8 May Hood and Adelaide sailed from Wellington up the east coast of the North Island, with Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Jellicoe aboard. As Governor-General of New Zealand, Jellicoe was due to officiate at ceremonies to honour the squadron in Auckland. Reputedly, he offered to stand watch overnight, apparently delighted to be at sea again. He had his family with him, including two of his daughters, Myrtle and Norah, who were returning to Woodford House, a girls’ school in Havelock North, an inland town not far from Napier.

By 8.00 am next morning the two warships stood off Napier, the largest town on the east coast of the North Island. Neither Napier’s breakwater harbour nor the nearby Inner Harbour could accept Hood, which anchored in the roadstead for a two-hour stop-over. Napier was crowded with visitors who had flocked in from inland districts to see the ship. Up to 40,000 people were estimated to have arrived, blocking all roads leading to the breakwater harbour. Boats were organised to take touring parties out. One woman – described in the media as an ‘elderly lady’ – tried to throw a bouquet of flowers aboard as the tour steamer circled Hood. The flowers fell short, but watching bluejackets fished the gift out of the water, ‘much to the donor’s delight’.[8]

Special efforts were made to get as many children as possible to see the ship. Back in 1913, the government had deliberately arranged for as many children as possible to visit HMS New Zealand in order to instill patriotic feelings in them, and the government repeated the exercise in 1924. Most of the administrative work fell to the Navy League. The Napier experience was both typical and remarkable. A total of around 5000 schoolchildren were taken out to see Hood,[9] many aboard vessels owned by local ship-owners Richardson and Company, others on the harbour dredge J. D. O..[10] It was an extraordinary feat of logistics given that the ship was only in the roadstead for a little under three hours. Some of the children were brought out aboard the sloop HMS Veronica, part of the Royal New Zealand Naval Division, which was small enough to berth in the Inner Harbour. While near Hood around 9.45 am, Veronica stopped to take aboard Myrtle and Norah Jellicoe, brought across by Hood’s Admiral’s Barge while a marine guard of honour saluted.[11] They were on their way back to school, and Veronica was small enough to enter Napier’s small Inner Harbour.

The only locals to board Hood during the stop-over were a small group of officials and media. First to arrive were Navy League Officials, who were on the water by 7.45 am aboard the Richardson & Company boat Ailsa, ready for Hood’s arrival. They were received by Vice-Admiral Field and taken through the ship. It was then that the photos in this article were apparently taken. Later a group of journalists came aboard. The sheer size of Hood was ‘brought home to the members of the party in the little launch’. The battlecruiser dwarfed all the other ships, a vessel of ‘huge build and vast potential strength…she seemed like some giant force slumbering peacefully until aroused by attack into a raging fury.’[12] Such words yet again underscored the fact that to the people of Empire, Hood had an emotional status.

The squadron regrouped off Napier: Danae, Dragon and Delhi arrived from Lyttelton and they shaped course for Auckland. Hood was about an hour late leaving, departing at 11.00 am.

It had been a remarkable event for the people of Hawke’s Bay: and it is clear that the everyday public were not so concerned with the minutiae of ship specification or even how they were classified. What counted at social level was the way Hood represented British power, the fact that she was the largest warship in the world. At this level of broad emotional meaning the engineering specifics were less crucial. And this fact was well known both to the Colonial Office and the Admiralty. The way Hood was represented in an everyday photo album, symbolically as the largest expression of military power in the world, underscores the way in which the British used the moral effect of their warships to add political weight to the Empire cruise.

Matthew Wright is a professional naval historian and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society at University College, London. Buy his book The Battlecruiser New Zealand: a gift to Empire (USNI Press 2021) https://www.usni.org/press/books/battlecruiser-new-zealand

Special thanks to Nick Jellicoe and his family, and to the Hawke’s Bay Knowledge Bank for permission to use pictures from their collection.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2025. Reproduction in any form, including by copying or sharing, is prohibited without prior approval of the copyright holder or the Navy General Board website administrator.

[1] It has since become the neologism ‘battlecruiser’, per usage in this article.

[2] Discussion of Hood classification as battlecruiser is at PRO ADM 1/9209

[3] See, e.g. Hawke’s Bay Tribune, 9 May 1924.

[4] Matthew Wright, Battlecruiser New Zealand, USNI Press, Annapolis 2021, pp. 88-115. I was the first historian to point out the wider political purpose of the voyage, something since plagiarised without credit for Wikipedia.

[5] See, e.g. Ben Markham, ‘The Challenge to ‘Informal’ Empire: Argentina, Chile and British Policy-Makers in the Immediate Aftermath of the First World War’, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, Vol. 45, No. 3, 2017, pp. 449-474.

[6] This conference was about far more than just naval limitations.

[7] Also used as the title of a book, Ernle Bradford, The Mighty Hood, Hodder & Stoughton, London 1959.

[8] Press, 16 May 1924.

[9] New Zealand Times, 10 May 1924.

[10] Hawke’s Bay Tribune, 9 May 1924. The dredge was named after the prominent Hawke’s Bay settler and early colonial administrator John Davies Ormond.

[11] New Zealand Times, 10 May 1924.

[12] Hawke’s Bay Tribune, 9 May 1924.

Recent Comments