On the first day of November 1914, the Royal Navy was to suffer its first

defeat in over a century, denting both its pride and the hard fought for,

Nelsonic image. But thirty-Seven days later, retribution in the form of

seven Royal Navy cruisers was to be delivered in an effort to rectify the

humiliation.

On a cold Tuesday, 8th December 1914, in the South Atlantic, deep

within the hulls of the two British Battlecruisers, HMS Invincible and

Inflexible, stokers worked in blast furnace like temperatures striving to

wring every extra knot possible from the two ships powerplants. Many

decks above in the four turrets, that housed the eight mammoth guns,

the weapons crews waited, frustrated, with their charges loaded,

waiting for the range to diminish and the order to commence fire to be

given. Looming high over the foremost turret, the bridge crews strained

through their binoculars to watch the largest of the smoke topped

smudges that lined the distant horizon. Since 10:00 that morning, the

British squadron had given chase from a standing start, their quarry

being the hastily retreating German East Asiatic Squadron.

Equally deep within those Germanic hulls, more stokers sweated in turn

before their own fires, to gain every extra knot, and then to demand

more. As hard as the British strove to close the distance, the German

commander, Vice-Admiral Maximilian Johannes Maria Hubert

Reichsgraf von Spee, sought to lead his ships to escape. His prayer was

for poor weather to shroud them from the intrusive British eyes, or to

survive the chase until the sun set, and the cloak of darkness could

finally shroud them from their tireless predators.

All that morning the British Commander-in-Chief, of the South Atlantic

and South Pacific Squadron (Vice-Admiral Frederick Charles Doveton

Sturdee) had watched as his seven ships, (HMS Invincible, Inflexible,

Kent, Carnarvon, Cornwall, Glasgow and Bristol), strove to draw the

intervening gap closed. But though the pursuit went far too slowly, the

British drew remorselessly ever closer to the Germans. Distant on the

horizon five smudges of funnel smoke marked the hard steaming SMS

Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Dresden, Leipzig and Nuremberg. But as the

minutes ticked by, the small dots under their individual plumbs of

smoke drew gradually larger before British eyes, and not smaller as the

German crews had prayed for. Each turn of the ships propellers brought

the day’s inevitable conclusion closer and it slowly became more

unavoidable for the German Admiral.

Hours earlier, while the British ships lay in port coaling, two German

cruisers had peered into the anchorage from out at sea. The intrusion

brought at 08:30 the Royal Navy crews summons to action stations. But

it was only after nearly three hours of steaming, at 12:55, that the

range was deemed on the flagship, HMS Invincible, to have been finally

reduced sufficiently for the guns to commence their afternoons work.

Orders were passed from Admiral, to Captain, from Captain to Gunnery

Officer, and then on down the chain to the waiting turret crews.

With the long-awaited order received, the elevation and direction the

turret crews had waited for was set. Slowly the turrets rotated, and the

barrels were lifted towards the distant goals. All was ready and now fire

was given, hurling those first shells out towards 14,000 yards. The shells

screamed down to create fleeting water sculptures near the German

armoured cruiser, Scharnhorst. The Invincible’s log soon claims two hits

to have be made. The Inflexible minutes later was to join the battle and hurl her own first salvoes across the watery void, towards the

Gneisenau.

Neither German ship gave answer to the challenge, ammunition was

too scarce to squander and the range was long, even for their 8.27-inch

guns. With one sea battle already fought (and won), the shortage of

ammunition was too much of a handicap to warrant the futility. But

finally, at 13:35, von Spee excepted escape for him was not to be

possible and the inevitable was upon him. Having released his three

light cruisers to try and seek an escape, he turned the Scharnhorst and

the Gneisenau to port to sacrifice themselves to permit the smaller

cruisers their opportunity to seek freedom. Only then did he permit the

half empty magazines to feed the waiting guns and fire to be returned

at the two Battlecruisers that had been snapping like terriers, at his

heels all that morning.

Both Vice-Admirals knew what outcome the day’s end would bring,

unless Germanic-luck was to intervene. By the day’s end, the

Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau would both be pounded to wrecks and

at rest upon the sea bed. It could only be inevitable, as a battlecruiser

so easily out classed the obsolete armoured cruiser. The unfolding

battle was the very reason for the battlecruiser concept. Was there

even a chance or a glimmer of hope for those German seamen so far

from home? Or was the disparity between the two warship types just

too much for the Germans to overcome? We already know the answer

to that pointless question, but indulge me, and let us see how big the

gap was that day, and if von Spee was doomed with no chance of

escape, or if his crews stood any chance of seeing a fresh South Atlantic

day.

First, let us begin with the size and weight of the days four main

combatants. The two German Armoured Cruisers were 474 feet 5

inches in length, which translates to 144.6 meters. To make an easier

visual comparison, if we were to take a modern four door family car,

which on average is listed as 15 feet (4.20. mtrs) in its length,

Gneisenau’s hull was thirty-one of those cars at her waterline, with a

smaller one door car tagged on at the end to complete the comparison.

Using the same automotive measurement, the Battlecruisers were at

their waterline, thirty-five (& a half) cars in length, or in dimensions,

530 feet 1 inch (161.57 meters). Thus, the difference between

armoured and battle cruiser was 55 feet 6 inches (16.97), or four cars

(11-12% longer).

In the matter of beam (or width), the Gneisenau was 70 feet 10 inches

(21.6 mtrs) and the Invincible 78 feet 10.13 inches (24.03 mtrs), the

difference being 8 feet, (2.43 mtrs). In the amount of draught, the four

hulls carried, the Armoured Cruisers were 27 feet 6 inches (8.277 mtrs)

and the Battlecruisers 29 ft 9 inches (9.07 mtrs) at deep load, so a

difference of 2 feet 3 inches, which for the weight of main caliber guns

carried, is a surprisingly small amount.

In weight or displacement, the Gneisenau was 11,433 long (Imperial or

British) tons while ‘unladen’ and the Invincible 17,290 long tons whilst

in a similar state, (51.22% difference). Once the coal, oil, munitions,

water, food and the thousands of items a warship needs to be ready for

sea were brought onboard, the totals increased respectively to 12,780

and 20,700 long tons, (61.97% difference). The 7,920 tons was

substantially more than von Spee’s detached light cruiser, SMS Emden,

which weighed normally 3,606 long tons and when fully loaded, 4,201

long tons.

Probably the heaviest weight contributing towards those displacements

were the turrets. The British ships each held four of the massive steel

fortifications, individually housing a pair of 12-inch guns. One turret

was situated facing forward over the bow, another facing aft. The

remaining two turrets were diagonally amidships. The weight of each

one of these four metallic fortresses was between 450 & 500 tons, (that

is about 383 of those family cars, per turret). In comparison the two

turrets mounted on each of the Armoured Cruisers were 88.6 tons as

single units (67-68 cars). If you were then to add the weights of the

individual barrels or guns to the turret weights, (Britain, 74 tons/56-57

cars & Germany, 19.70 tons/15-16 cars per barrel), approximate total

of 648 tons/497 cars and 128 tons/ 87-88 cars per turret is reached.

The British turrets were of such a huge size in comparison, that one 12-

inch barrel alone equated to 83.52% of one (all be it without gun

barrels) Germanic turret and the total individual weights differed by

520 tons/399 cars.

We will keep the question of the level of power supplied from each

engine room simple. The Scharnhorst’s three propellers gave

revolutions for 22.5 knots, and the Invincible’s four in turn provided

26.48 knots. The 3.98 knot difference is a good walking speed, given the

average person strides out at 4.58 mph. But it also needs to be factored

in that all four ships had just completed long voyages to the Falklands,

(12,000+ miles for the Germans & 7,000+ miles for the British), and

with the marine growth accumulated on the hulls during these voyages differing in the quantity, their maximum speeds would have been

affected to varying amounts.

Finally, before we move on, for every hour Sturdee’s ships had given

chase, the distance between the four ships diminished by 4.58 miles

(7.37 km), a figure worth bearing in mind when we come to the reach

of the main caliber and how soon the British guns could realistically

expect to be within range of their goals.

The next subject that needs to be examined is the reason for the ships

existence, the main caliber guns. Everything was secondary to these

weapons and was there merely to serve and support them in one-way

or another. The engines existed to ensure the guns could be delivered

safely to where they were required. The crews (Invincible up to 1,000 in

wartime, Gneisenau 764) were on-board to either directly serve the

guns or to support them in a subordinate mode. The secondary guns

purpose was to fend off threats to the hull, and thus preserve the all-

important big guns.

The Gneisenau’s main gun caliber was comprised of eight 8.27-inch (21

cm) guns, four of which, (as we have noted), were mounted within two

turrets. Equally, the Invincible had eight 12-inch (30.5 cm) guns,

mounted into four turrets. The superiority of the British guns is obvious

with a difference of 3.7 inches (9.39 cm), but as obvious as the size

disparity was, how much authority had those 3.7 inches given to the

British crews?

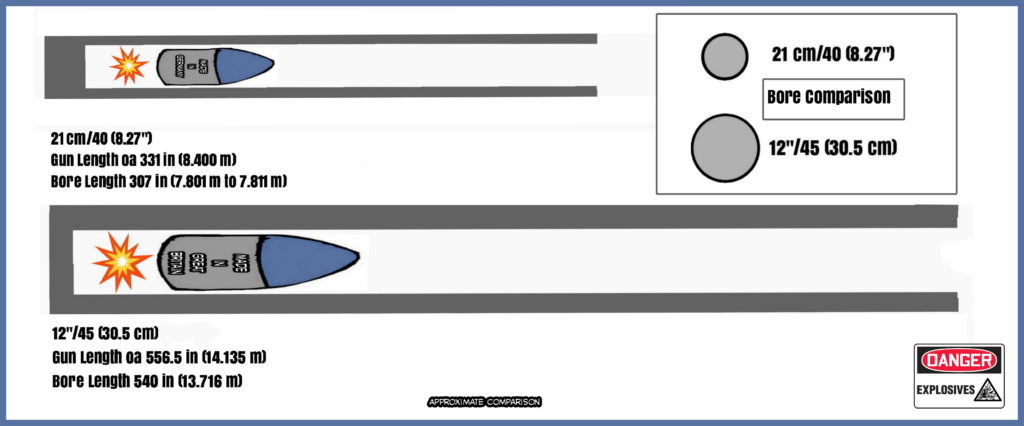

Each of the German four 8.27-inch turreted guns (C/01 version) were

27 feet, 7 inches (8.407 mtrs)1.83 cars)) in length, with a bore measurement of 25 feet 7 inches (7.797 mtrs). The weapons

individually weighed 44,137 lbs. (20,020 kg), or 20.02 tons. That is

around 15-16 of those family cars, per weight of per barrel. These

Krupp designed and manufactured weapons were the Armoured

Cruisers primary armament, being mounted on the center line in two

twin gun turrets, one fore and one aft of the main superstructure. The

four remaining 8.27-inch guns (C/04 version) were mounted within

single casemates amidships, two facing out to port and two to

starboard. The C/04 was marginally lighter than the C/O1, at 41,667

lbs., (18,900 kg) and whereas the turreted C/O1 was hydraulically

powered, the casement CO/4 was electrically trained and manually

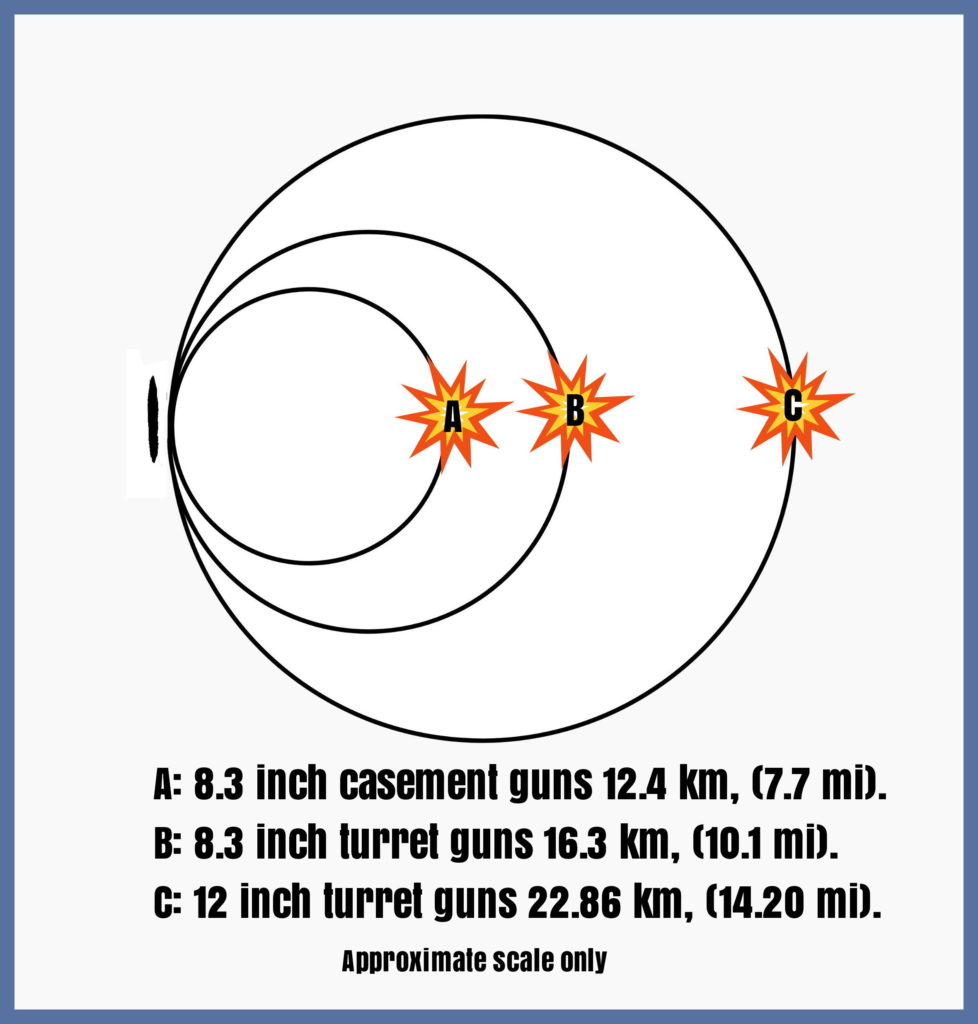

elevated. By their very placement within the hull, the casemented guns

were restricted in their maximum elevation to 16 degrees a total of 14

points less than their turreted siblings. The gun placements allowed the

two Armoured Cruisers a broadside of six guns on both beams, but

bizarrely, over two maximum ranges.

The British 12-inch gun (mark ‘X’ version) was 46 feet 4.5 inches (14.135

mtrs) 3-4 cars)) in length, with a bore of 45 feet (13.716 mtrs). The

individual weapon, (with breech) weighed 129,348 lbs. (58,626 kg) or

57.74 tons. Using the family car comparison once more, the single gun

weight equates to 44-45 of our four-door car. The German 8.27 inch

were 18 feet 9 inches (or 59.53%) shorter than their British adversaries

in their overall length.

The British ships had in theory a broadside of four turrets and eight

guns. The two centrally mounted turrets were staggered in their

placement, giving them the capacity to fire on either beam by shooting

across the width of the mid-ship deck. But at “ the Falklands battle,

Invincible fired cross-deck with both P and Q turret but this dazed

and deafened the gun-layers, trainers and sight setters as well as

causing blast damage to the deck. P turret reported that the

trainers had to be replaced constantly during the battle as they

were too dazed to function properly. After the battle, cross-deck

firing was ruled out except in cases of emergency.” [

http://www.navweaps.com/] As a result, the eight-gun broadside was after the battle restricted to

six, (unless it was a matter of life or death), but for this one

engagement the Battlecruisers fielded all eight of their main weapons.

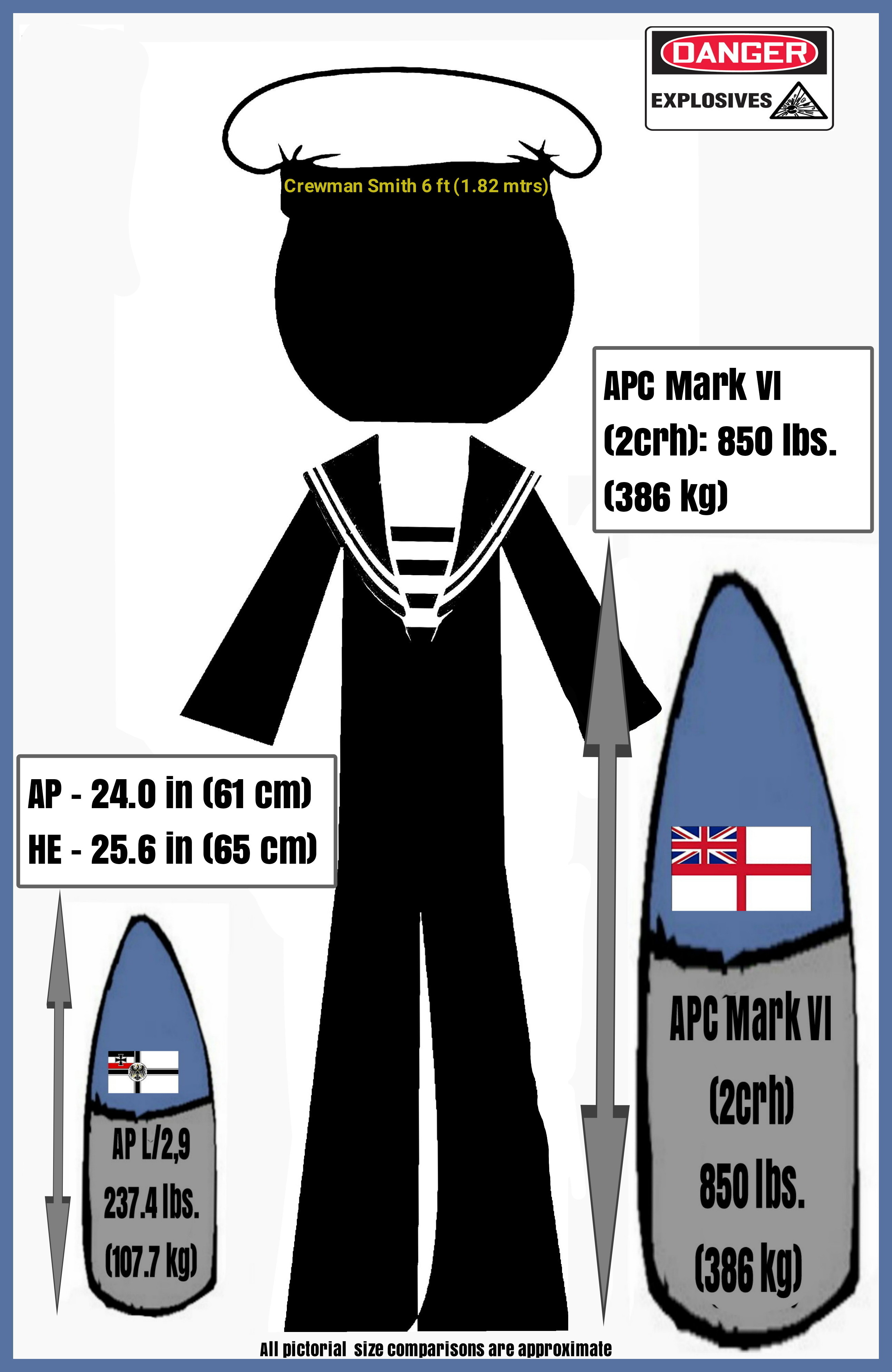

But having delivered their 8.27 or 12-inch shells on target, how much

damage did they inflict on their detonation? The Gneisenau’s armour

piercings shells weighed 237.4 lbs. (107.7 kg) and the casement guns,

when fired at a 16-degree elevation, could dispatch one of those

projectiles a distance of 7.7 miles (12.4 km). But the four turreted 8.27-

inch guns, (with their greater elevation of 30°), could deliver their shells

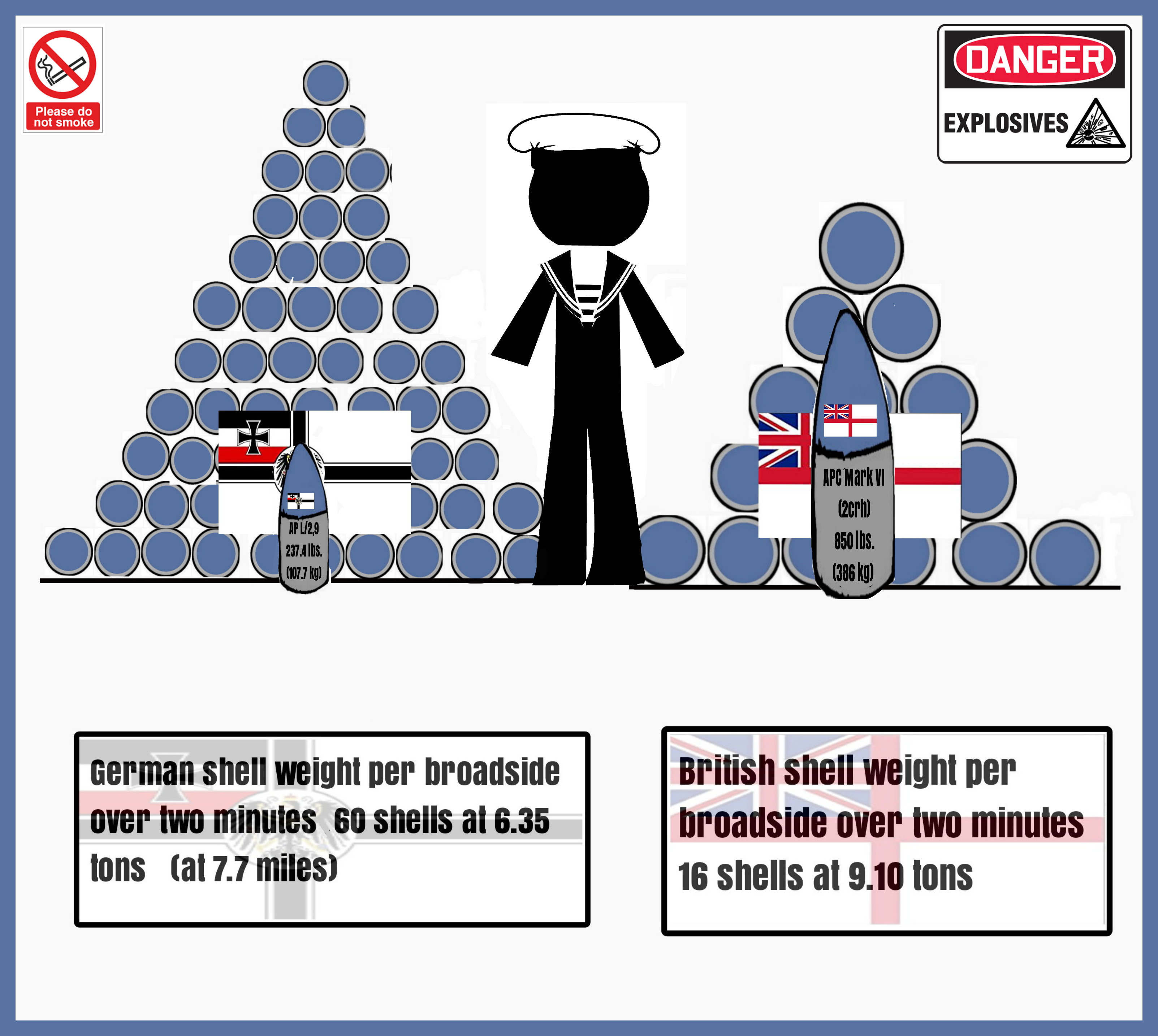

a further 2.4 miles, reaching out to 10.10 miles (16.3 km). A good and

well-trained gun crew, (both ships had prior to the war, won the

prestigious Kaiser’s Schießpreis (Kaisers Shooting Prize), (Scharnhorst in

1909/10 & Gneisenau 1908/1909 & 1910/11)) would be able to achieve

between 4 and 5 salvos per minute. Depending on the elevation

available, in those sixty seconds, 20 to 30 shells would cross the void

that lay between the battling adversaries, travelling at 1,744.81 mph

(2,808 kph). The total weight of shell fired within a two-minute period

was 6.35 tons at 7.7 miles or 4.23 tons at 10.10 miles.

The British APC shells in turn weighed 850 lbs., a staggering 613 lb.

(258%) increase over the German projectile. The heavier shell could be propelled out to a maximum of 14.20 miles (22.86 km), travelling at a

faster 1857.95 mph, out ranging their German opponents by 4.20 miles.

Over a two-minute period the Germans fired up to 10 broadsides, and

the British 3 salvoes. Even with the slower rate of fire (1.5 per minute)

achievable by the British, their heavier shell dominated the German

response at 9.10 tons per 2 minutes, a 2.75-ton dominance at 7.7 miles,

and 4.87 tons at 10.10 miles.

The 4.20 miles by which the Germans were out ranged by the British

12-inch, would have required the Armoured Cruisers at their top speed

of 22 knots, a tortuously long 11 minutes 20 seconds to cross. Only

once having somehow steamed faster than the British, plus having also

survived the 17 uncontested salvos those 11 minutes plus would allow

and finally successfully crossed that British shooting range, could the

Germans give reply with their two ships four turrets. Those 11 minutes

plus would have most likely felt to the German crews as the longest 680

seconds in their life’s.

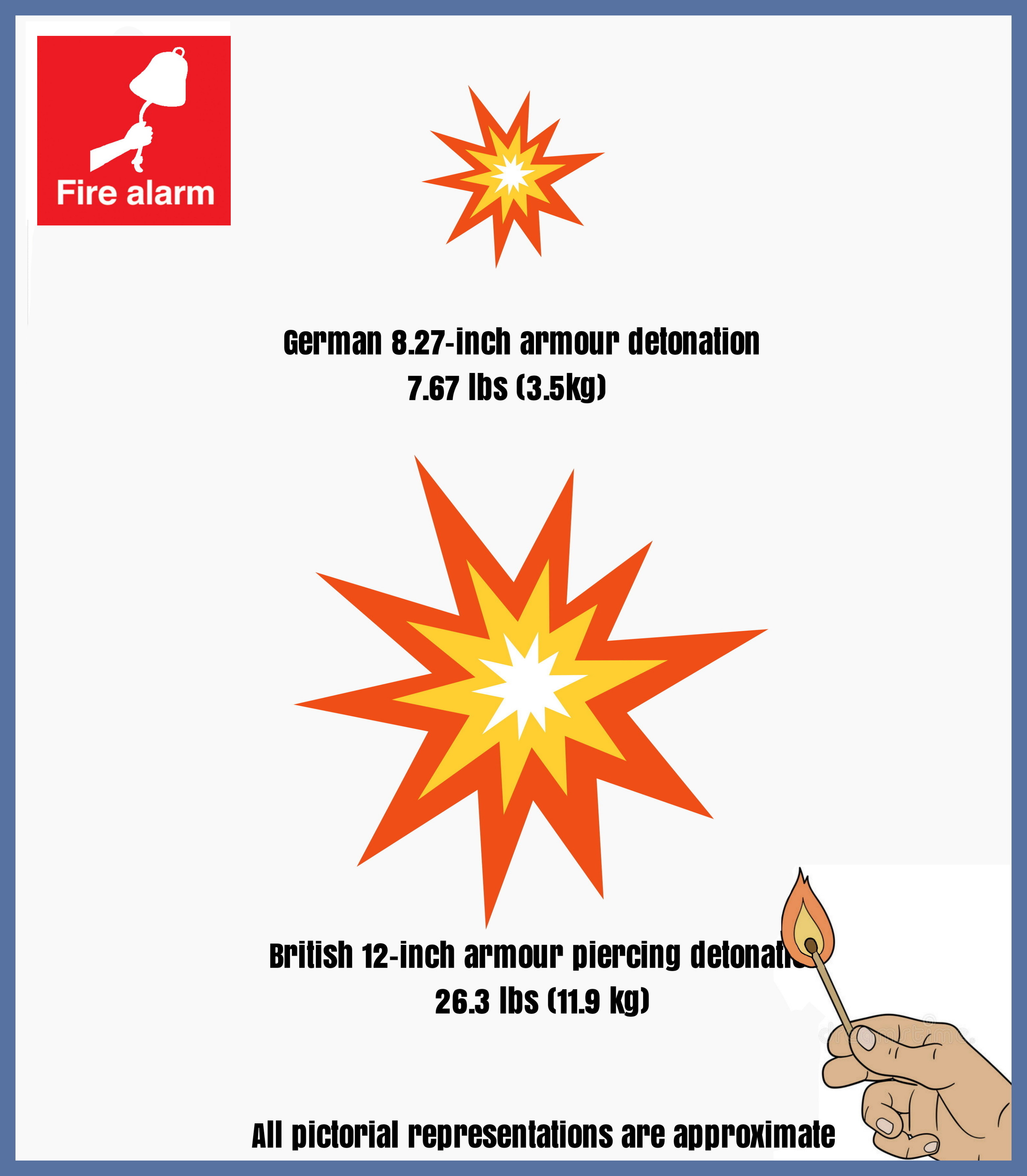

As the German and British shells plummeted down around their

respective targets, the German exploded with a force of 7.67 lbs. (3.5

kg) [AP L2,9], and the 12-inch British shell [APC Mark VI] with 26.3 lbs.

(11.9 kg). As a result of the slower rate of fire, the British shells had an

18.63 lb. larger explosive force. The Invincible’s eight-gun broadside

could in theory deliver 631.2 Ibs. of explosive force per two minutes

within the target area. However, using just, the four quicker firing 8.27-

inch turreted guns, the Germans could deliver 306.8 Ibs. per two

minutes. But if von Spee could lure the Battlecruisers to within range of

both the turret and casement guns, he could deliver his heaviest

broadside at 460.2 Ibs. weight of explosive force over those 120

seconds. However, getting the shells onto their target is nothing, if the

detonation lacks the force to penetrate the enemies armour on impact.

In the 1904 edition of Janes Fighting Ships the German shell is noted as

having the power to penetrate 6.5 inches of armour at 5,000 yards, and

9 inches at 3,000 yards. In response, at 10,000 yards (9,144 mtrs) the

British shell could pierce 10.6″ (269 mm), and at 7,600 yards (6,950

mtrs), 12-inches (305 mm) of armour. Given those figures, the

Armoured Cruisers had no armour that could withstand an impact by

the 12-inch shells being hurled at them. In turn the German shells were

capable of penetrating the Battlecruisers belt at between 4,000 and

5,000 yards. The deck armour was vulnerable at less than 6000 yards,

but the turret would require the range to be closed to less than 5,000

yards. The 10-inches of the conning tower would necessitate a suicidal

range less than the 3,000 yards.

The only other major factor to consider was the content of the

magazines. The German squadron had already fought one battle off

Chile’s coastline the month before and had also conducted several

bombardments as they had steamed their way east across the Pacific.

We do not know the quantity of the limited shell supply that remained

to the German gun crews, how many were Armour piercing and how

many were High Explosive? Only the former were of any significance on

the day, but for how long could the guns be supplied with them? It is

likely given the two Armoured Cruisers faced at Coronel, a significant

proportion had been expended to ensure their rapid demise.

By the time, the first salvoes were fired on that December day, the

sources report that the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau’s magazines were

only 40% full, which (given each gun had a supply of 85 shells), equates

to 35 per gun, which is less than ten minutes of rapid firing. By the time,

the Gneisenau had come to near the end of her struggle, the survivor’s

reported her magazines to have been empty and the gunners resorting

to using non-explosive training rounds. Even with those, Gneisenau was

still able to land shells onto her tormentors. We can assume that the

Scharnhorst was lost before her magazines were empty, as her guns

were still active as she finally succumbed to the damage wrought on

her. But given the 100% mortality rate on that dying ship, we will never

know if those final shells were training or live. But both the Armoured

Cruisers lived up to their prize-winning shooting reputation and were to

deprive the British of the simple and easy victory their dominance

would imply.

One final factor was the quality of the crews that served the guns and

sailed the warships on that day. A large percentage of the British crews

were drawn from the Royal Naval Reserve and had only in the last few

months been recalled to the colours. A new crew takes time to settle in

and to reach peak efficency. The German crews were the polar

opposite, having in the majority served together both in time of peace

and war. The crew members served two years each on the China

station, 50% being rotated home every year. The German sailors were

on that December day, amoungst the finest and well-trained serving on

any warship at that period.

TO CONCLUDE.

From the other side of the battle, British gunnery was poor, at one

point in the exchange achieving 4 hits out of the 210 shells fired (1.9%).

It was to be claimed post battle that the smoke from the guns and

funnels, since the Battlecruisers were upwind of the Germans, had

been the cause. But British gunnery right up until late 1916 was

generally less accurate with the opening shots than their Germanic

cousins. In turn the Invincible had fired 513 shells from her main guns

during the battle but achieved only twenty-two hits (4.28%).

Inflexible fired 661 twelve-inch shells during the battle but was hit in

return three times due to her obstruction by the Invincible’s smoke. The

Invincible was to suffer two of her bow compartments flooded, and one

hit on her waterline below ‘P’ turret which had caused a flooded coal

bunker. This inflicted her with a temporarily 15° list.

At the start of this article, we already knew von Spee and his two

sacrificial Armoured Cruisers were doomed. As they turned to face their

assailants, they were facing up to odds that were insurmountable. But

now we know how large that doom was. It has been confirmed that the

Battlecruisers were dominant in both their displacement and

dimensions. Everything about the two British ships was bigger,

something the main caliber guns and their shells demonstrated. But

three factors were the signposts that pointed to that doom.

1: No matter how hard the German stokers worked at their furnaces,

the British superior speed was always going to close the gap. Only poor

weather and the arrival of nights cloak of darkness would allow the

Germans to break free, but there was insufficient time remaining on

the days clock for those to play a role on that day.

2: The German gunners could send far more shells towards their British

opponents with every salvo. But they were working from heavily

depleted magazines and faced in turn British magazines that were

stocked to capacity. The British could fire until the German magazines

were emptied and had nothing but empty racks, and then carry on as

the 8.27-inch guns fell permanently silent.

The smaller number of British shells that landed around and

occasionally on the German ships were larger and carried a greater

destructive force. But the gunners on the Armoured Cruisers were

hampered in an already one-sided exchange by the range limitations of

the casement guns. Von Spee needed to close the range to maximize

his broadside weight, but he lacked the superior speed to achieve that.

No matter what he did, and how superior his gunners aim was, the

German volume of shell was out matched by the bigger British bang.

3: The German 8.27-inch shells were obviously significantly lighter than

the British shells, and until the range was diminished, which without

the speed advantage was not going to happen, the British armour

would defy the efforts of the German armour piercing shells to

penetrate the Battlecruisers vitals.

But such a problem did not face the British gunners, and the few shells

they hit home with, would pierce the defending armor, and enter the

ships interiors, where their bigger detonation would cause more

damage. The Germans could pepper the opponents all afternoon with

continuous hits, but if they somehow entered the British ships vitals,

their detonation and destructive force was considerably less than the

British shells. Nonetheless the 12-inch shells, even if they hit home far

more infrequently, caused catastrophic and fatal damage.

From that last turn to port, von Spee was sacrificing his two biggest

ships, but the only influence he had was on the price the British paid

and the damage it caused to the Battlecruisers exteriors. It was typical

of a great Admiral and was both brave and fatal, it was just a question

of how long it took to prove to be so.

Want to read more great articles by Andy South? Check out some of his other articles!

Recent Comments