In 1919 the embittered Admiral Sir John Fisher, former First Sea Lord and the long-standing champion of naval technology, summed up his recent thinking about heavy warships in three words: ‘speed is armour’.[1] The phrase has since been inextricably associated with his ideas throughout the dreadnought era, skewing the way we see the evolution of heavy warships during the first two decades of the twentieth century. By this thinking Fisher, as Britain’s volcanic First Sea Lord from 1904-10 and again in 1914-15, reputedly invented the battlecruiser and set the pattern by which such ships foolishly sacrificed armour for speed.

This idea surfaces time and again as if true online.[2] It has also been taken ‘as read’ in numerous histories of warship engineering, and at academic level was not questioned until late in the twentieth century. Even then, such ideas died hard and the so-called ‘revisionist’ arguments played out in recent years have largely missed the key points. Such thinking speaks more to the effectiveness of Fisher’s self-promotion than it does about what happened.

In fact the evolution of British heavy warships from the late 1890s to the end of the First World War is more nuanced the tropes allow. We saw in an earlier article how Fisher’s thinking evolved from the 1890s in parallel with similar changes of idea towards heavy warships of the period. This, as we saw, led directly and quickly to the concept of fast battleships, which Fisher first tried to introduce in late 1905.[3] The failure of that proposal underscores the fact that he had less influence than he liked to admit. Much of his subsequent association with battlecruisers came because he promoted speed in all warships, was a master manipulator of the media, and associated himself personally with both Dreadnought and the ‘dreadnought armoured cruisers’ of the 1905-06 programme even though they compromised what he really wanted. Later he started advocating speed at the expense of armour, which represented significant shift of thinking. Why? As we shall explore in this article, his reasoning was largely political.[4]

Fisher’s self-promotion masked the fact that the First Sea Lord had limited powers. He could urge, push, lobby and manipulate. He could stack the deck with supporters – his ‘Fishpond’ – and did so. But he could be overridden by the Board, and he could not directly control either ship design or building programmes.[5] These decisions were taken by the Board of Admiralty which, in turn, had to bow to Cabinet over key financial decisions at a time when government was trying to drive down defence spending. In the pre-First World War years this meant the Board had to make compromises that they felt would be politically palatable. Fisher’s thinking also went through distinct stages, and only reached extremes after 1910, when he retired from the Admiralty and had freedom to let his imagination roam without the tempering influence of the Board and his advisors. It was then that the ‘speed is armour’ dictum emerged, though he did not publish that in as many words until 1919.[6]

Ship design was a tricky balancing act that ran beyond simply balancing guns, armour and speed against limits on displacement. Other factors included access to specific docks, draught to enable access to particular harbours, speed at specific displacements and hull conditions, and a raft of other practical factors. Fisher’s ideas went through phases. As we saw in the previous article, his ideas of the 1900-04 period involved new types of fast warships. His thinking evolved, but the type he eventually came up with for his Naval Necessities change-blueprint of 1904 was a multi-role, mid-sized and fast armoured ship akin to the Napoleonic-era frigate. This was never built. Fisher’s ideas also joined others in the Admiralty, part of a general churn in naval design that began in the late 1890s on the back of a raft of new technologies. In Britain, however, this churn was also framed by the frameworks that had emerged in the 1890s where annual construction included a balance of the heaviest types, armoured cruisers and battleships. This was, in effect, hard-coded into the system by the time Fisher arrived to the point where forward plans were built around the armoured cruiser/battleship mix. Fisher’s initial concept of fast intermediate vessels had no chance.

One of the associated challenges was the fact that naval designers from Washington to London, from Berlin to Tokyo, had no idea how the new technologies would perform. Warship designers of the Napoleonic era had centuries of experience to draw from: they knew exactly how ships performed, exactly what the weaponry of the day would do. The engineers of the early twentieth century had no such advantage. Shells could be tested against armour in proving grounds, occasional full-scale experiments run. But the enormous depth of experience that had buoyed naval design in the age of sail did not exist.

This added intensity to the fiscal pressures. Nobody could afford to make mistakes, yet nobody quite knew how things would work. Britain was particularly affected because the pressure to keep costs down vied with the pressure to keep the Royal Navy ahead of rivals. As Nicholas Lambert has observed, the issue was further complicated by a deliberate effort to preserve the private-sector arms industry.[7] One outcome was that although the Board of Admiralty shared Fisher’s notion that change in ship designs was necessary, he had to retain the battleship-cruiser split. What emerged for the 1905-06 programme was therefore the all-big-gun battleship and its cruiser equivalent, which at the time was seen as the logical extension of the armoured cruiser concept.

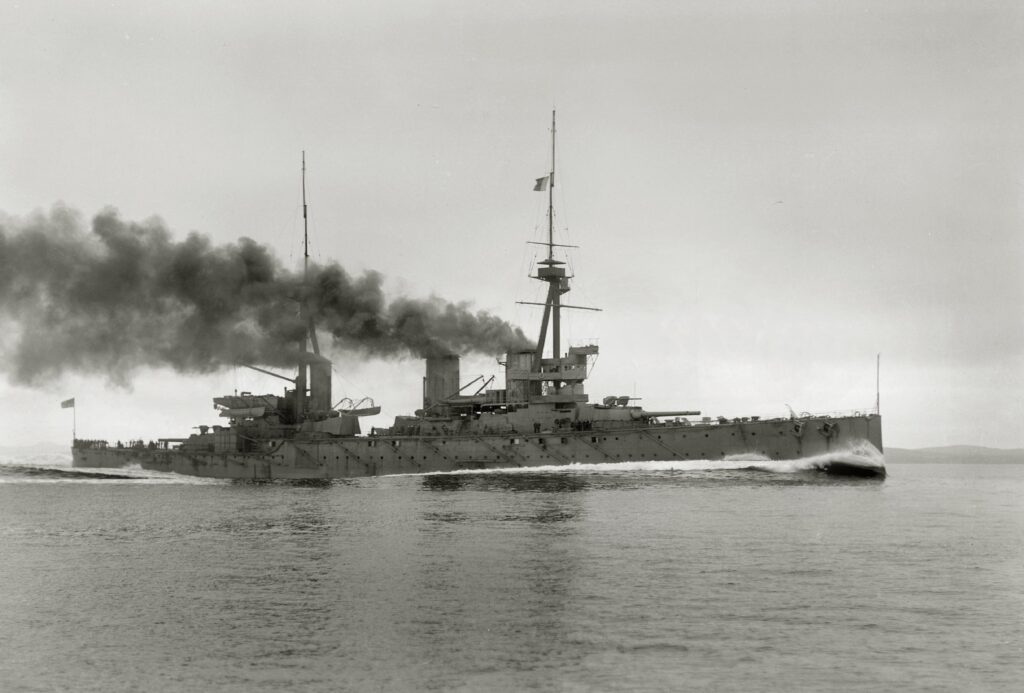

As we saw in the previous article neither Fisher nor his advisors intended to sacrifice armour at this stage. Britain’s first ‘all big gun’ cruisers, designed and built in 1904-07, were as well armoured as any of that type.[8] The problem was that a 12-inch armament rendered them over-gunned. Fisher also saw them as a compromise. He wanted a single type of heavy ship, properly armoured and fast, so the following year tried a ‘fusion’ design, blending cruiser speed with dreadnought armament and protection.[9] Prior studies by the Admiralty had shown that a ‘fast’ heavy ship required a three-knot advantage over the battle line for tactical purposes, so the sketch designs were specified for 24 knots. This was the first fast battleship and makes clear that the concept was well understood. But the idea was knocked back, largely because Fisher’s 1905-06 Committee on Designs was unwilling to render their construction of the year before obsolete.[10]

Fisher tried again with the 1907-08 programme, which he initiated in late 1906. This time he accepted that the battleship-armoured cruiser split was politically embedded. But now he wanted a cruiser with more protection, more fire-power and at least the same speed as Invincible. Displacement was again an issue for cost reasons. Watts produced a variety of options with belt armour ranging from 8 to 10 inches. In December 1906 the Board finally approved a design with 9-inch belt and new 50-calibre 12-inch guns.[11] Fisher also wanted another ‘fusion’ battleship, again with battleship-scale armour, this time on the basis that the new fire-control system devised by Arthur Pollen would improve its long-range fire-power.[12]

These requests make clear that to this point Fisher had no intention of sacrificing protection in favour of speed. The Director of Naval Construction, Philip Watts, produced multiple sketch designs. As with the ‘fusion’ ship of the year before, these featured triple turrets as weight-saving devices. The Board of Admiralty were unimpressed; if a triple turret proved problematic the armament would be downgraded with twin turrets, which was unacceptable. All this then foundered on politics: the Board finally decided to cancel the cruiser and Cabinet allowed only three further improved Dreadnoughts, which became the St. Vincent class.

The political issue was unsurprising. Britain was locked into an arms race with Germany in which the pressure was on to limit the rate of increase in displacement, hence cost. This was given teeth by long-standing government policy of not borrowing to meet peacetime military spending. Funding all had to come out of income at a time when government was focusing on resolving social problems.

Fisher did not relent, proposing what he called HMS Nonpariel, the first of several concepts he labelled with that name.[13] This retained a 9-inch belt, but he now wanted 13.5-inch guns. That jump in fire-power rendered the protection marginal on the principle that a ship should be protected against its own guns. But to Fisher the priority was now fire-power and speed. He also called for negligible superstructure to reduce the size of the target. This was not practical from the perspective of ship handling and operations, still less fire-control. What this concept underscored was the fact that Fisher’s ideal balance of speed, protection and fire-power was shifting away from armour. All was academic, though: once again his idea was rejected. The ‘dreadnought armoured cruiser’ authorized for the 1908-09 programme was instead a cheaper edition of the earlier Invincible. This was materially less than Fisher wanted, although he bragged about her as if she had the innovations he had been calling for.[14]

By this time the lesson was clear: budgetary constraints were squashing Fisher’s ideas one after another. His problem was further underscored in the 1909-10 programme. The DNC, Phillip Watts, came up with two battleship designs deploying the new 13.5-inch gun, one of 21 knots and a larger vessel capable of 23. Fisher wanted the faster design, but was overridden by the Board: it was going to cost an additional £150,000.[15] The same fate befell options for a new ‘dreadnought armoured cruiser’, HMS Lion, which was developed with Fisher’s input. Watts offered two designs. The first had eight 13.5-inch guns, following prior precedent in which cruisers carried two guns less than their battleship equivalent. Watts then realized that if he extended the hull by three frames he could make room for an additional turret. This would have produced a 25 percent increase in fire-power over the 8-gun ship for just 7 percent greater cost.[16] He produced a design, but even this modest rise in expense was deemed unacceptable, and Lion was signed off for eight guns.

Despite this knock-back, Lion brought Fisher’s ideas to fruition in some respects, albeit filtered by Board requirements and the compromises inevitable to Admiralty politics. The ship was closer to his ‘fusion’ concept than Indefatigable. Her armour protection was better than Indefatigable – the belt, for example, was 50 percent thicker. While that was still marginal when set against her 13.5-inch guns, at practical level it was more effective than Indefatigable’s protection when facing German 11- and 12-inch fire.

Fisher’s next setback followed almost at once. Four capital ships were authorized for the 1909-10 programme along with two ‘contingent’ vessels. Fisher was keen to have all six built as Lions, but what was actually authorised was an initial programme of two 12-inch gunned battleships, one 13.5-inch gunned battleship and one Lion. A political fracas followed in early 1909 over the two contingent ships, leading to a peculiar compromise: Cabinet authorized four additional ships – one more Lion and three 13.5-inch battleships. Fisher did not get his six Lions. The same political crisis provoked first New Zealand and then Australia to offer gift ships to Britain, which Fisher managed to transmute into batttlecruisers. But the type allocated was the older Indefatigable.

Fisher retired as First Sea Lord in 1910 and the following year became de facto advisor to the navy’s new political head, Winston Churchill. Amidst the need to keep displacement constrained, Fisher now began moving more decisively towards the idea that armour could be compromised in favour of speed and fire-power. ‘You only want enough thickness of armour to make the shell burst outside.’ This represented a shift from his earlier views. Fisher continued to press his ideas over the next few years, veering further into extremes. He also continued to push for any new technology, however radical. By 1912 he was trying to get his next idea built, a motor-ship with ten on-board torpedo motor-boats and no superstructure. He saw huge advantages in having diesel engines, ranging from reduced engine-room staff to weight savings. He had Vickers produce plans – Design 623 – but his scheme got nowhere. It frustrated him. ‘We must press forward,’ he fumed to his friend Lord Esher. ‘These d – d politics are barring the way.’[17]

Politics certainly were barring the way – and had been throughout his career at the top of the Royal Navy. His swing from about 1909-10 and beyond towards compromising armour in favour of speed and fire-power was one outcome, a line he continued to push from that time. Eventually he reached extremes, which we shall examine in the third and final article of this series.

Matthew Wright is a professional naval historian and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society at University College, London. Buy his book The Battlecruiser New Zealand: a gift to Empire (USNI Press 2021) https://www.usni.org/press/books/battlecruiser-new-zealand

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2024

[1] Fisher, Memories, p. 98

[2] See, e.g. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_battlecruisers_of_the_Royal_Navy; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Invincible-class_battlecruiser etc.

[3] https://www.navygeneralboard.com/admiral-sir-john-fisher-and-the-first-fast-battleships/

[4] As argued in https://www.navygeneralboard.com/admiral-sir-john-fisher-and-the-first-fast-battleships/

[5] Fisher’s place and relationships have been masterfully analysed by his biographer Ruddock Mackay, Fisher of Kilverstone, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1973.

[6] Fisher, Memories, p. 98.

[7] Nicholas A. Lambert, Sir John Fisher’s Naval Revolution, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, 2002, pp. 146-147.

[8] See, e.g. P. K. Kemp (ed) The Fisher Papers Volume I, Navy Records Society, Routledge, Oxford 1960, p. 87.

[9] Variously noted, see e.g. Friedman p.

[10] Todd Christopher Campbell, ‘Financing the Royal Navy, 1905-1914: sound finance in the Dreadnought era’, MA thesis, University of British Columbia, 1994, p. 21.

[11] Friedman, p. 100.

[12] Lambert, p. 144.

[13] Compare, e.g. Memories, p. 219.

[14] Ie: 10 is 125 percent of 8. See, e.g. R. A. Burt, British Battleships of World War 1, Seaforth, Barnsley 2012, p. 106.

[15] Friedman, p. 117.

[16] Friedman, p. 117.

[17] Cited in, Memories, p. 219.