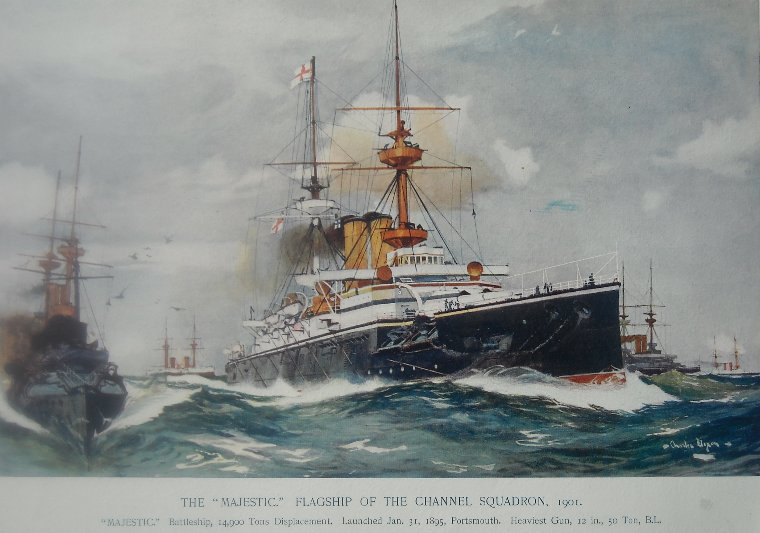

Britain’s Majestic class of the 1890s was the largest class of battleships ever built. In many ways the nine-strong class symbolised the age. The names selected for them were redolent of the period, particularly the neo-classical revival that had become a British Imperial motif: Majestic, Caesar, Mars, Jupiter, Hannibal, Magnificent, Illustrious, Prince George and Victorious.[1]

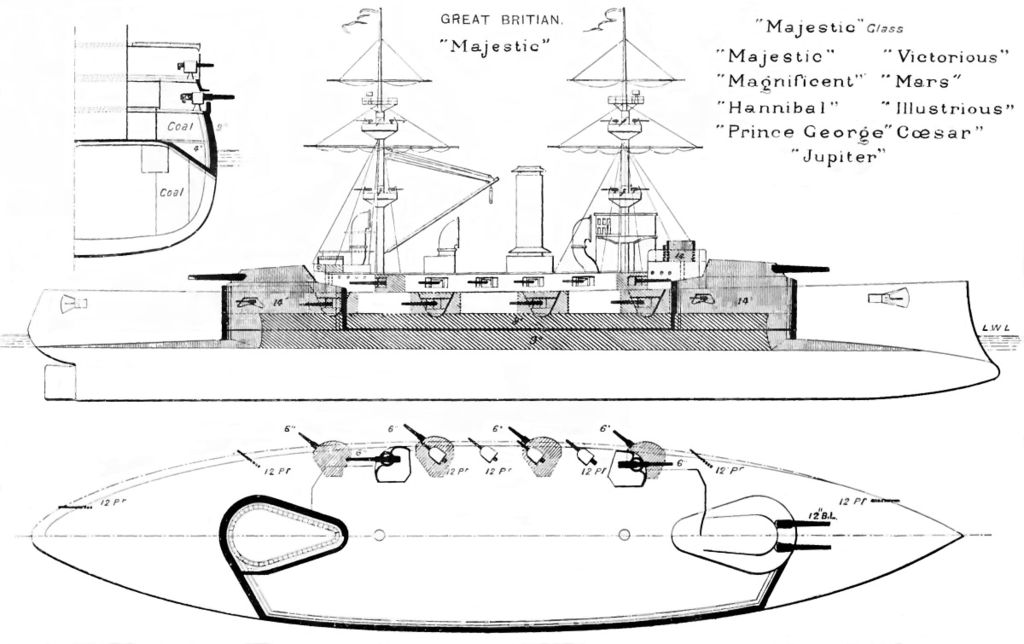

The Majestic class were technically innovative, introducing a new heavy gun, improved-technology armour, a new style of armour distribution, and armoured gun-houses atop the two barbettes that carried the main armament. Incremental improvements were included in the later examples of the class. In general they were a model for subsequent British battleships into the early twentieth century.[2] Three foreign battleships built in British yards, Japan’s two Shikishima class and the later Mikasa, were broadly based on the Majestic design.[3]

This engineering would have given the class a place in naval history even without their unprecedented number. What isn’t so well remembered, though, is the political battle that swirled around their origins – which, in part, was responsible for ending the long and illustrious career of one of Queen Victoria’s two great Prime Ministers, William Gladstone.[4]

Then there is the way the class were funded, which as we shall see in the next article, involved death duties.

The origins of the Majestic class can be traced back to the 1889 Naval Defence Act and the two-power standard, by which the Royal Navy was required to be at least equal to the next two world naval powers combined – at the time, France and Russia. In 1889, eight first-class and two second-class battleships were authorised to meet the new standard. They were also of a new high-freeboard type. Debate over the layout and design of major warships had been raging through the 1880s, producing a variety of classes ranging from barbette ships such as the ‘Admirals’ – click here for details – to turret ships such as Victoria, detailed in three articles on this site: here, here and here. Now, thanks to the talented Director of Naval Construction, William White, seven of the eight first-class battleships authorised by the act took a new approach, with high freeboard giving them a level of sea-keeping that had been lacking in the 1880s battle-fleet.

This class, the Royal Sovereigns, were built over the next few years and further battleships to this general pattern were obviously the way forward. More ships were also going to be needed to keep up the self-imposed ‘two power’ standard, as other nations continued to build battleships. However, the government was reluctant to fund more battleships in 1890-91. That went doubly so for a Liberal government under the elderly Prime Minister William Gladstone, which took power in mid-August 1892 and appointed a new First Lord of the Admiralty, John Poyntz Spencer, the Fifth Earl Spencer.[5]

To some extent the Board of Admiralty did not want to push the battleship issue too far, as technology was also maturing. A new 12-inch/35 calibre gun was under design.[6] This offered significant improvements over older 13.5-inch/30 calibre weapons.[7] However, in 1890 this new weapon was still some way off. New armour technology was also emerging, particularly Harvey-process steel which combined a hardened face with softer back in a single piece of metal. This was invented by US engineer Hayward Harvey in 1889, though not patented in Britain until 1891.[8] British armour manufacturer Vickers, Sons & Co equipped themselves to make it, and tests in 1892 showed it was more effective than older compound armour.[9]

The Admiralty hoped three battleships could be authorised for the 1892-93 programme and a further two in 1893-94. They didn’t get them. However, design work continued on possible vessels, guided by the Controller, Rear-Admiral John Fisher – a long-time advocate of technology who had called for the new quick-firing 6-inch/40 calibre gun for the Royal Sovereigns.[10] As Controller he was pushing every technology, including destroyers – a new ship type of the day.[11] When it came to battleships he wanted the new 12-inch guns and Harvey armour at sea. That armour technology had been used to a limited extent in the two second-class battleships authorised in 1889. Now Fisher wanted it adopted generally. White obliged, delivering initial sketch designs for possible first-class battleships in January 1892. These exploited Harvey armour to cut displacement relative to the Royal Sovereigns, and introduced armoured gun-houses atop the barbettes.

These gun-houses were an interesting development. One of the early criticisms of open barbette mountings was that they left gun crews exposed to enemy fire. That could be largely corrected by siting the loading equipment and crew down inside the barbette, but that in turn restricted loading to one position – usually fore-and-aft – and reduced the rate of fire. This was one of the key reasons why the ‘barbette vs turret’ debates of the 1880s had been so intense. The obvious answer was to fit an armoured gun-house atop the barbette and devise all-round loading systems, but that also brought weight and stability considerations into the picture. Now, with lighter – but tougher – armour and lighter 12-inch guns, it became possible. The technology was introduced in stages across the Majestics. All were designed with an armoured gun-house atop the barbette, but the first seven members of the class retained a fixed loading position with hydraulic rammers, apparently because White preferred that system. This was partially compensated for by siting eight ready-use rounds in the mount itself.[12] The final two, Caesar and Illustrious, had all-round loading.[13] This system soon gained the name ‘turret’, although in engineering terms it was different from the older style round ‘turrets’ of the mid-late nineteenth century.[14]

The Board wanted three of these battleships for the 1892-93 programme, but didn’t get them, in part because the new 12-inch gun was delayed, but mainly because of the political refusal to authorise the ships. A single second-class battleship, Renown, was instead ordered in 1892, according to one source largely to keep the work-force in the Pembroke dockyard occupied.[15] The Controller, Rear-Admiral John Fisher, rather liked this design because of its speed and lobbied for a class of six, but did not get them.[16]

This did, at least, give White and his team opportunity to further refine the new ships, and design work on possible first-class battleships went on in parallel with the development of Renown.[17] They were conceptually similar. Aside from enclosed gun-houses, both also introduced a new concept for overall protection. This set the general pattern for the battleships that followed into the early twentieth century. White had long felt that the 6-inch quick-firing ‘secondary’ guns proliferating on most battleship designs were a major threat at the expected battle ranges of the day. They might not penetrate the thickest armour, but they could still deal with thinner plates, and unarmoured areas were highly vulnerable. The 6”/40-calibre guns introduced on Royal Sovereign and planned for the Majestics were capable of firing 5-7 rounds a minute.[18] This rate, coupled with their number, produced a high chance of scoring hits. The ability of the quick-firers to devastate unarmoured or only lightly protected areas – in modern terms, to deliver a ‘mission kill’ – was judged to be high.

White’s new armour scheme was designed to avert this problem with thinner but more extensive side-armour than prior ships, proof to 6-inch shells, and backed by a sloped armoured deck intended to catch anything that got through.[19] The barbettes, meanwhile, were proof to heavy shells. This innovation was made technically possible by the new Harvey armour with its superior protection-to-weight ratio. The precise details of the Majestic class armour distribution and thickness went through a variety of reviews – in part because the ends were unarmoured, which caused concern after the Victoria was rammed forwards and sank in June 1893.[20] (For details, click here). However, White’s system was generally adopted for both Renown and the new first-class battleships.[21]

The interesting point is that it was a further move away from the ‘all or nothing’ idea that had been proposed for some earlier British battleships, notably Inflexible of the mid-1870s.[22] But it was a practical way of protecting ships against what White considered the key gun threat of the 1890s. The ‘all or nothing’ approach was then re-invented by US naval architects in the early twentieth century when the smaller quick-firers lost the place they had in the 1890s, and protection had to be re-thought yet again to meet the all-big-gun paradigm.[23]

White’s proposed first-class battleships, in short, were cutting edge for their day. By mid-1893, the designs were broadly developed and the name of the class, Majestic, had been selected.[24] The Second Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Frederick Richards, was pressing for a major programme to keep up with French and Russian developments.[25] Actually building them, though, was another matter. Gladstone’s government didn’t want them. And what followed was a political battle royale in which somebody had to lose.

We shall pick that story up in the next article. Meanwhile, check out my book The Battlecruiser New Zealand: A Gift to Empire, detailing the politics behind that ship and her career in the First World War.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2020

[1] Roger Chesneau and Eugene M. Kolesnik (eds), Conway’s All The World’s Fighting Ships 1860-1905, Conway Maritime Press, London 1979, p. 34.

[2] Norman Friedman, British Battleships of the Victorian Era, Seaforth, Barnsley 2018, pp. 262-282.

[3] Chesneau and Kolesnik (eds), pp. 221-222.

[4] For summary biography see https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Ewart-Gladstone, accessed 6 July 2020.

[5] See http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/John_Poyntz_Spencer,_Fifth_Earl_Spencer, accessed July 2020.

[6] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_12-35_mk8.php, accessed 6 July 2020.

[7] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_135-30_mk1.php, accessed 6 July 2020.

[8] David Bournsell, ‘The British Armour Plate Pool Agreement of 1903’, in John Jordan and Stephen Dent (eds), Warship 2017, Bloomsbury, London 2017, pp. 25-27.

[9] Ibid, p. 27.

[10] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_6-40_mk1.php, accessed 6 July 2020.

[11] Ruddock Mackay, Fisher of Kilverstone, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1973, pp.205-207.

[12] Burt, p. 144.

[13] Ibid, p. 145.

[14] For discussion see https://www.navalgazing.net/Turret-and-Barbette, accessed 6 July 2020.

[15] Friedman, p. 254.

[16] Mackay, p. 213.

[17] Friedman, p. 257.

[18] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_6-40_mk1.php, accessed 6 July 2020.

[19] See, e.g., Burt, p. 154; Friedman, p. 252.

[20] Burt, p. 155.

[21] Friedman, p. 261.

[22] Inflexible’s design origins were complex: see Friedman, pp. 161-162.

[23] Norman Friedman, US Battleships: An Illustrated Design History, Naval Insitute Press 1985, pp. 101-102.

[24] Friedman, p. 258.

[25] Mackay, p. 209.

Recent Comments