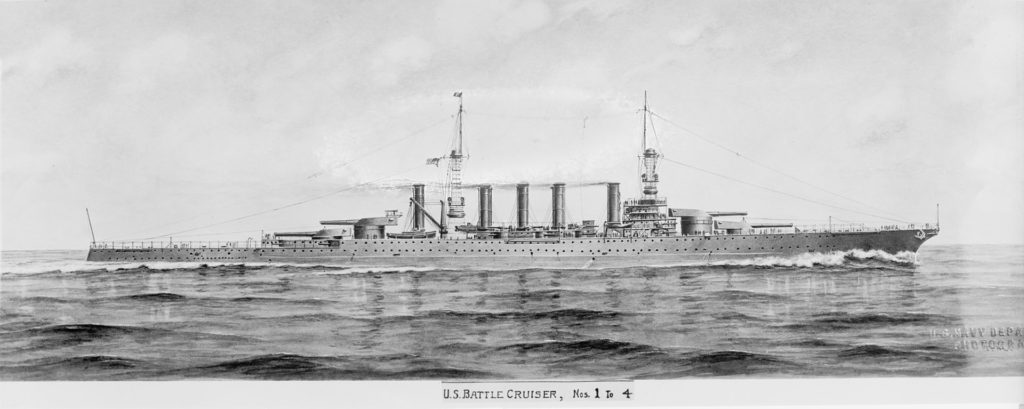

The United States Navy’s only planned battlecruisers, six Lexington class ships authorised by the Naval Act 1916,[1] were cancelled by the Five Power (‘Washington’) Treaty of 1922.[2] Two – Lexington and Saratoga – were completed as aircraft carriers instead.[3] The battlecruisers have often been considered something of a side-issue for a US Navy that was primarily interested in well-armed and armoured battleships.

In fact, these battlecruisers had a central place in US naval thinking at the time. Their concept reflected a prevailing US Navy battle doctrine of ‘aggressive offensive action’. The same style of thinking was also applied to the designs of the first US ‘Treaty’ cruisers of the early 1920s.[4] And the Lexingtons drew from specifically American tactical naval needs and thinking.

So how did they come about? The origins of US battlecruiser thinking can be traced to the naval ferment around the turn of the twentieth century when, like the British, French, Germans and Japanese – among others – US naval authorities were looking at the implications of a recent jump in the power of large warships. Heavy ships of the mid-late 1890s typically came in two flavours: battleships with a few heavy guns and a range of smaller weapons, backed with faster armoured cruisers that carried a few medium guns and a usually similar array of smaller weapons.

By the last years of the nineteenth century, however, battleships were gaining medium guns on top of the rest – literally in the United States, where the medium guns were at times housed atop the main armament.[5] The rise in fire-power also influenced armoured cruiser designs, which gained displacement and scale of fire-power comparable to second-class battleships, yet retained greater speed.[6] These developments then fed into emerging thinking about how the design components – protection, fire-power, sea-keeping, speed, range, displacement and habitability – could be mixed. Tactics and technology, in short, were entwined; and a conceptual revolution involving both was well under way by 1901-02.

Although a relative late-comer as a nineteenth century naval power, the United States was well up with the play. In 1902, Lieutenant Matthew Signor proposed a new type of battleship featuring six 13-inch guns and a battery of 10-inch. That was followed in 1903 with other proposals for a heavier armoured cruiser – essentially a fast battleship, in terms of the standards of the day. The idea was further endorsed by the Naval War College Summer Conference of 1904.[7] But cost was an issue. Into this was mixed warring theories about how naval battles might be fought. One result was tension between the conceptual ship proposals of the Naval War College and the more conservative designs prepared by the Bureau of Design and Repair. In a way it was predictable; the College could engage in blue-sky exercises, whereas the Bureau had the task of making warships reality, which included managing financial constraints and the political views that drove them.

By 1904-05, all-big-gun battleships were on drawing boards in Japan, the United States and Britain. However, the British, pushed by Fisher – as First Sea Lord – added turbine propulsion, completed their prototype, Dreadnought, ahead of the rest, and extended the concept to an all-big-gun cruiser design. These ships, the Invincibles , were initially classed as armoured cruisers[8] – the ‘battlecruiser’ designation was not formally applied by the British until 1911. Exactly what Fisher intended has been debated. Beating the latest armoured cruisers was one motive, demanding a significant step-up in fire power but no increase in armour. There was also the concept of such ships being a fast scouting wing, able to deliver heavy punch to the enemy battle-fleet.[9]

This thinking was shared across the Admiralty. However, Fisher also felt the heavy gun had won the gun-vs-armour race. Because ships were going to be size-limited, primarily for cost reasons, he felt it better to put displacement into speed and massive guns.[10] Heavy armour was unnecessary.[11] So too was anything other than minimal lighter weaponry. As Norman Friedman observes, by 1915 Fisher even opposed the heavier secondary guns required for anti-destroyer work.[12]

The crucial point is that Fisher felt that all heavy construction should go into such faster ships. As early as 1902 he was arguing that there was little distinction between armoured cruisers and battleships. ‘The Armoured Cruiser…is a swift battleship in disguise’.[13] And this is the point: to Fisher, the evolved armoured cruiser became a replacement for the battleship. As First Sea Lord from late 1904 he put a good deal of effort into trying to persuade the rest of the Admiralty and the Cabinet to agree. In a way, he had a point. A fast ship with monster guns could keep a safe distance while dealing out massive blows. Fisher was not the first to come up with this idea: the Italian naval designer Benedetto Brin had explored it in the 1870s.

However, while this gained ground in Fisher’s circles – a group dubbed the ‘Fishpond’,[14] the rest of the Admiralty disagreed. All an enemy had to do was build faster ships with larger and longer-ranged guns. And ships with speed superiority on paper might not be able to choose the range, thanks to weather or a raft of other factors such as loss of speed due to damage, or operational issues such as hull fouling, break-down or damage. For these reasons, Admiralty thinking leaned towards armour. The obvious answer was the fast battleship. However, although designs were mooted as early as 1906,[15] they were unacceptably expensive to British governments trying to constrain military spending.

In the end, Fisher never convinced either the Admiralty or the British government to authorise battlecruisers in number. The original three were a windfall; the 1904-1905 building programme called for one battleship and three armoured cruisers on the basis that Britain was under-strength in the latter.[16] Before any were laid down, Fisher’s Committee on Designs produced the Dreadnought and its cruiser homologue, the Invincible – and so Britain got one all big-gun battleship and three all big-gun armoured cruisers, later dubbed battlecruisers. But aside from the 1908 ‘naval panic’ with the ‘contingency’ programme approved in August 1909, only one battlecruiser was then usually authorised in each annual schedule, and the type was abandoned altogether in the 1912 programme. Battlecruisers were not re-visited until Fisher’s return to the Admiralty in 1914.

There was similar tension in the United States, where Britain’s Invincible design of 1905 seemed to meet aspects of Naval War College thinking about faster and more heavily armed cruisers. However, proposals from various American naval pressure groups, publications and the Naval War College during 1907-08 to build Invincible-class ships instead of new US armoured cruisers were apparently an academic and profile-raising exercise.[17] In fact, there was no chance even of indigenous US battlecruiser designs being authorised. More than one historical analysis argues that the US government had no clear naval policy at the time.[18] More crucially, budgets were constrained. Congress typically authorised about half the number of battleships variously recommended by the General Board or the Bureau of Construction and Repair.[19]

But in any case, while professional opinion within the US Navy was better-defined than in government – thanks in part to the Naval War College[20] – thinking leaned towards heavily armed and armoured battleships with moderate speed but good unrefuelled range. This was largely to meet US strategic commitments of the day, which focused on trans-Pacific interests. Such ships were intended to form a solid battle-line, to which the enemy would have to come if they were to defeat the United States at sea. This influenced the occasional foray into faster vessels. In 1910, the Chief Constructor of the Bureau of Construction and Repair, Rear-Admiral Washington L. Capps, organised six potential designs for fast all-big-gun armoured cruisers, which had relatively modest speed by the British battlecruiser standards of that period – 25.5 knots – but with armour closer to contemporary US battleship scale. These were rejected by the General Board, which felt such ships were cruisers, and what the US Navy needed were more battleships.[21]

Yet, within a few years, the US Navy was indeed pursuing the idea of battlecruisers – and, furthermore, battlecruisers with the massive fire-power, remarkable speed and thin armour that Fisher thought ideal. But this was for wholly US-developed motives, which diverged from Fisher’s reasoning. Proposals along the way included a surreal 1,250 foot long monster displacing over 60,000 tons. We shall pick up the story of how that happened, and how the latest mainstream British ideas about heavier armour then infused themselves into US battlecruiser thinking, in the next article.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2019

[1] For brief discussion see Eugene Edward Beiriger, ‘Building a navy “second to none”: the US Naval Act of 1916, American attitudes towards Great Britain, and the First World War’, British Journal of Military History, Vol. 3, No. 3, June 2017, pp. 4-5.

[2] https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000002-0351.pdf

[3] For brief summaries see, e.g. https://www.navy.mil/navydata/nav_legacy.asp?id=12, and https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/uss-lexington-carrier.html

[4] Trent Hone, ‘Building a doctrine: U.S. Naval Tactics and Battle Plans in the Inter-War period’, International Journal of Naval History, Vol . 1, No. 2, October 2002, p. 15.

[5] See, e.g. Roger Chesneau and Eugene M. Kolesnik (eds), Conway’s All The World’s Fighting Ships 1860-1905,Conway Maritime Press, London 1979, p. 143.

[6] Ibid, pp. 72-73, for instance.

[7] William M. McBride, ‘Nineteenth century American warships: the pursuit of exceptionalist design’, in Don Leggett and Richard Dunn (eds), Re-inventing the Ship: Science, Technology and the Maritime World, 1800-1918, Routledge, London, 2012 p. 202.

[8] Norman Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-1946, Seaforth, Barnsley, 2015, p. 90.

[9] Ibid, pp 84-88.

[10] Noted in ibid, p. 178.

[11] Jon Tetsuro Sumida, ‘British capital ship design and fire control in the Dreadnought era: Sir John Fisher, Arthur Hungerford Pollen and the Battle Cruiser’, Journal of Modern History, Vol. 51, No. 2, 1979, pp. 205-220.

[12] Friedman, p. 172.

[13] Ruddock F. Mackay, Fisher of Kilverstone, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1973, p. 270.

[14] Ryan Peeks, ‘Battlecruisers in the United States and the United Kingdom 1902-1922’, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/b/battlecruisers-in-the-united-states-and-the-united-kingdom-1902-1922.html.

[15] See, e.g. Friedman, p. 95.

[16] Ibid, p. 77.

[17] Ryan Peeks, ‘Battlecruisers in the United States and the United Kingdom 1902-1922’, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/b/battlecruisers-in-the-united-states-and-the-united-kingdom-1902-1922.html

[18] Joseph W. Kirschbaum, ‘The 1916 Naval Expansion Act: Planning for a Navy Second to None’, PhD thesis, George Washington University 2008, pp 8-15, summarises the historiography; and government policy pp 19-26.

[19] Ibid, pp. 26-27.

[20] Ibid, p. 29.

[21] Ryan Peeks, ‘Battlecruisers in the United States and the United Kingdom 1902-1922’, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/b/battlecruisers-in-the-united-states-and-the-united-kingdom-1902-1922.html