Designs for the first American battlecruisers, the Lexington class, were developed across several major incarnations during and soon after the First World War. We traced the origins of the American battlecruiser – first as concept, then as designs flowing from the mid-war effort to build a first-class navy – in the previous three articles: here, here and here. This final article in the series looks at the way the Lexington battlecruiser design was re-framed around British lessons – and at how post-war international politics finally overtook the whole scheme.

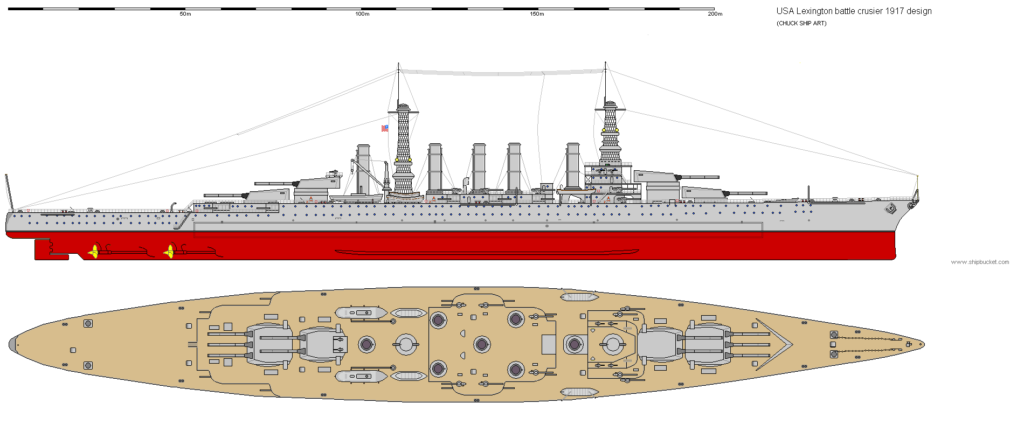

By late 1917 the Lexington design had already been through two major versions;[1] the initial 1916-17 form with ten 14-inch guns,[2] then a modified version produced later with eight 16-inch.[3] However, as general information about evolving British war experiences arrived – in part via a London office opened by the commander of US naval forces in Europe, Vice-Admiral William Sims –[4] there were concerns about protection. This consisted of extensive but relatively thin deck and side armour. [5] The General Board looked into that in January 1918,[6] and in February, the Bureau of Ordnance asked the British Naval Attache in Washington, Guy Gaunt, for any information the British had about battlecruiser armour. The Admiralty responded that the Americans had already been provided with designs for HMS Hood.[7]

It appeared that the Bureau of Ordnance was not talking to its counterpart, the Bureau of Construction and Repair (BC&R) – possibly because they were in different buildings. In fact, the BC&R did not merely have plans for the Hood, they had a British designer on staff. Early in December 1917 the British despatched one of their most talented young constructors, Stanley Vernon Goodall, to the United States. He went ostensibly as an assistant naval attache with their embassy. Actually, he joined the BC&R the day after he arrived – and, as shown by naval architect and historian Larrie Ferreiro in a 2006 study – was treated as part of the US constructors’ team.[8] The Americans, in turn, sent their constructor Lewis McBride – already in London – to work with the Constructors’ Department in the Admiralty.[9]

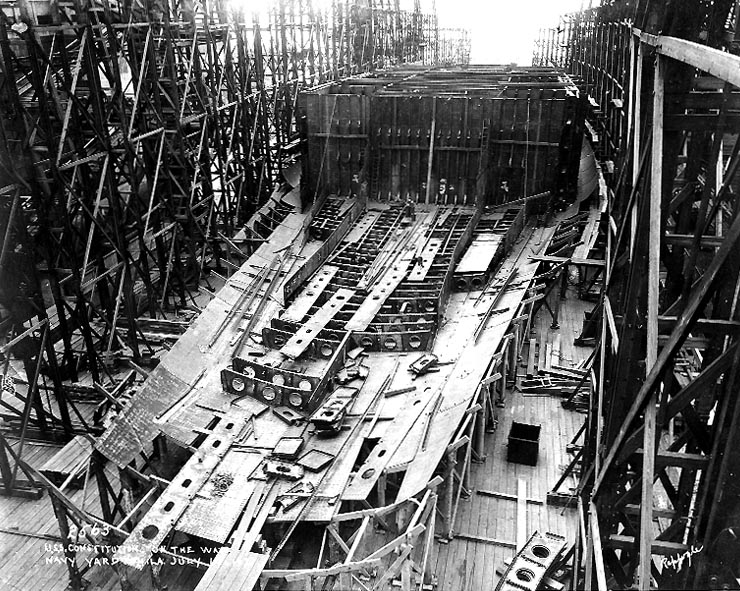

Goodall arrived at a time of change. By late 1917 the BC&R comprised 11 naval constructors and 25 designers and draftsmen.[10] In mid-1918 the unit moved from the Washington Navy Yard into a new building on Constitution Avenue, joining the other bureaus involved with aspects of ship design.[11]

Ferreiro’s study has shown that Goodall provided information to the Admiralty and to the Director of Naval Construction, Sir Eustace Tennyson D’Eyncourt, about US design practices;[12] but the greater flow was the other way. During his 15 months in the United States, Goodall provided US designers with the latest British thinking on many details of warship design and engineering, writing some 109 memoranda.[13] As Ferreiro shows, Goodall’s input gained a further dimension when, after a brief stint in the destroyer branch, he was shifted to the battleship and battlecruiser section.[14]

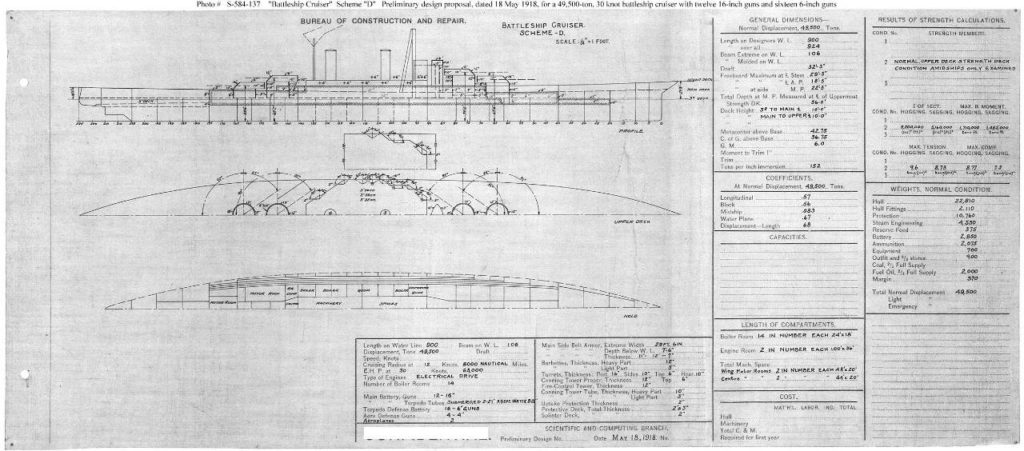

The idea of combining battleship-scale armour and high speed, as offered by Hood, had been in the BC&R’s sights for some time, largely thanks to Sims.[15] Goodall’s arrival offered opportunity to take that a step further. In April 1918, the chief Constructor, David Taylor, ordered his staff to develop options for what were basically fast battleships.[16] Two competing teams were formed, producing sketches ranging in concept from Goodall’s 49,500 ton Scheme D ‘battleship cruiser’ of 18 May,[17] to James Bates’ Scheme B, which was labelled an ‘improved battlecruiser’.[18] The different nomenclature was academic: all these designs were pursuing the same general goal. Goodall’s design specified a dozen 16-inch guns, armour around 10 percent less than that of the South Dakota class battleships, and a speed of 30 knots.[19] One point to note is that these were all sketch designs; had any been built, their particulars would have differed once the specific engineering details were worked out. However, none were. Proposals were put to the General Board in June and promptly rejected, in part because such designs rendered prior ships obsolete and would ‘demand a re-building of the fleet’.[20]

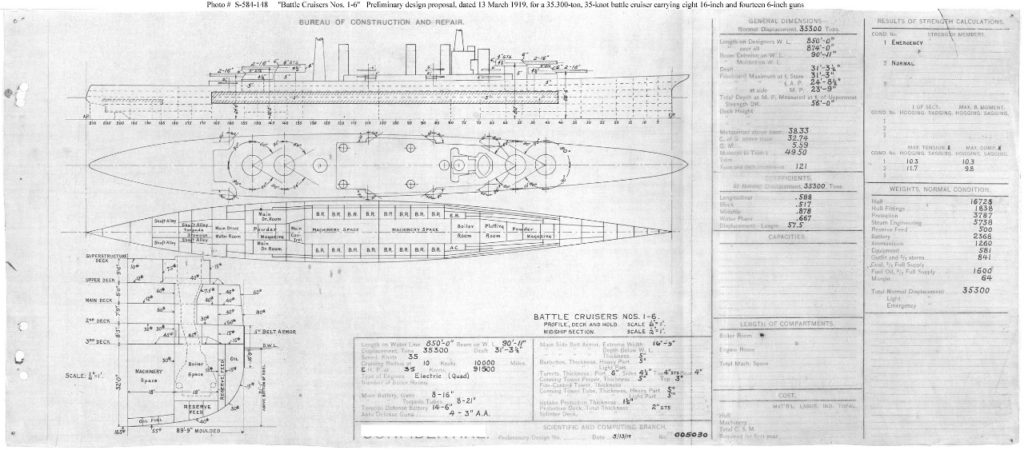

The work was not wasted, however, because this style of thinking then fed into final revisions of the Lexington design. This was produced during 1919, expanding from one of Goodall’s drafts.[21] As Ferreiro argues, the general concept was thus effectively Goodall’s.[22] Some detail was, it seems, also provided by a plan the BC&R drew up around this time for Hood, [23] on the basis of the data provided locally in Washington by Goodall, and from London by McBride.[24] However, in other aspects the final Lexington design was quintessentially American, including the turbo-electric drive.[25] This underscored the way that trans-Atlantic information-exchange shaped, informed, and inspired – but did not wholly overwhelm – thinking in Washington.

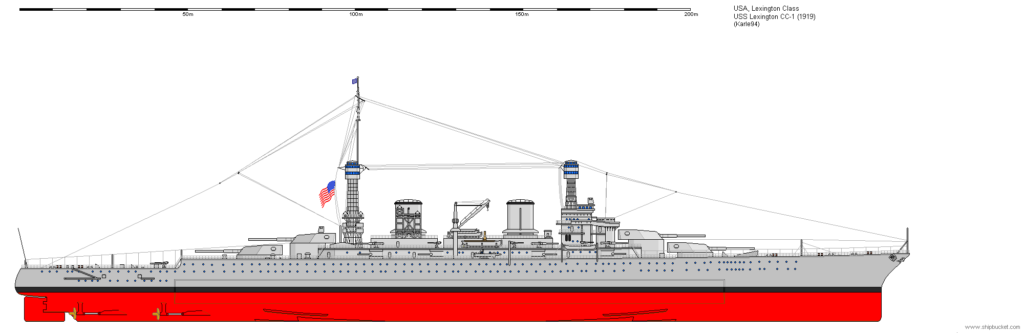

The final Lexington design retained the main battery of eight 16-inch guns,[26] but featured improved and sloped belt armour – an innovation taken directly from Hood – with all boilers beneath a thicker armoured deck, two funnels, and an estimated full-load displacement of over 44,500 tons.[27] Armour now accounted for 28.5 percent of displacement, just 4.5 percent less than Hood.[28] The 180,000 horsepower propulsion plant gave a theoretical design speed of 33.5 knots.[29] Underwater hydrodynamics were assisted by a bulbous bow thought likely to reduce drag by up to 6 percent over 25 knots.[30] Had the battlecruisers been completed, maximum speed could have been higher; the two Lexingtons built as aircraft carriers could reach overload figures of over 210,000 hp.[31]

The Lexingtons finally emerged, in short, as powerful warships with excellent fire-power, outstanding speed, and armour that – although still not up to what the British now believed necessary – was better than in earlier incarnations of the design, and significantly so at specific ranges.

However, despite being authorised by law, nothing could be done with these designs until funding was confirmed. In late 1918 the General Board proposed a further 28 capital ships.[32] Wilson slashed the proposal to 16, but evidently saw them as combining with the 1916 plan to create a bargaining tool against Britain, urging Congress to provide money for the 1916 programme and to accept the 1918 extension.[33] Congress declined the 1918 proposal, but the 1916 programme with its 10 battleships and 6 battlecruisers as the centrepieces remained alive, and there were clashes during talks in Paris early in 1919 when British diplomats demanded to know why the United States wanted such a large navy. The dispute became so heated that Josephus Daniels, Secretary of the Navy, called it the ‘Naval Battle of Paris’.[34] It might have turned into a significant rift. However, after talks between Lord Robert Cecil and Wilson’s aides, the British agreed to support US calls for the Monroe Doctrine to be part of the League of Nations covenant, in exchange for the US postponing work on some of the ships authorised in 1916.[35]

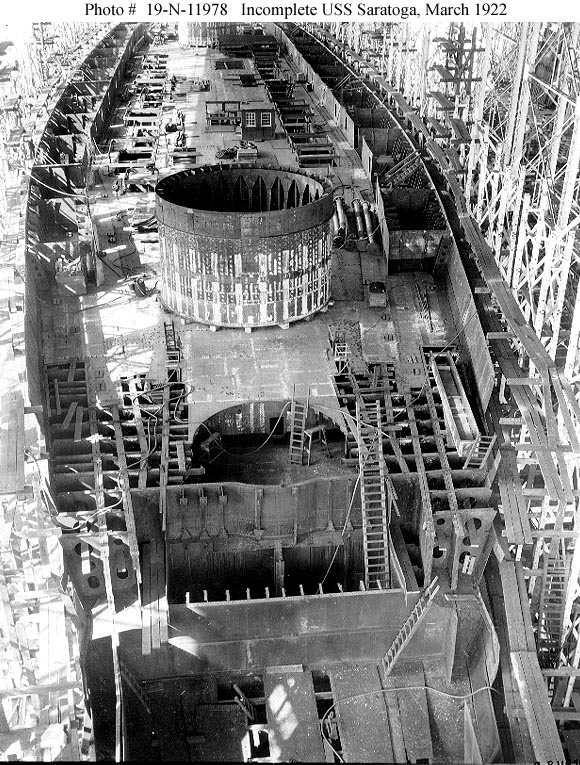

The battlecruisers were finally given start funding in fiscal year 1920. Constellation (CC 2) was laid down in August and the rest followed over the next months into 1921.[36] However, their future was threatened by a sharp recession that struck the US economy from 1920.[37] In November 1920 a new President, Warren Harding, was elected on a platform of spending cuts and reduced foreign policy intervention.[38] His thinking was supported within the Senate, notably by William Borah, whose calls for global cuts in naval spending – including American – struck a domestic political chord.[39]

That idea also fell on receptive ears in Britain, where the coalition government of David Lloyd-George was opposed to major naval construction for financial reasons.[40] Indeed, the British had been anticipating an international naval-limitation agreement since 1919. When Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Jellicoe wrote to the Admiralty in June that year, asking for details of future building programmes,[41] he was brusquely informed that these depended ‘on negotiations for limitations of armaments’, and that construction until then was ‘confined…to completion of ships in an advanced stage’.[42]

Now, in 1921, such a conference seemed on the cards. Harding’s administration took some months to shake down but – on 8 July – issued formal invitations to the major nations for an international conference in November.[43] As we will explore in a separate article (forthcoming), this conference, considered likely even during its proposal phase in early 1921, was one of several reasons why Lloyd-George’s government relented and authorised a significant British capital ship programme that year, as a bargaining tool.

However, the conference was always going to be about more than just naval arms limitation. It was also a reflection of the the general re-balancing of world politics, economies, and global power in wake of the First World War. Global problems included general US-British relations, western influence in Asia, and Britain’s need to end or renew the Anglo-Japanese Alliance,[44] all of which were inter-related with the new naval arms race.[45] Other European nations such as France and Italy were interested in a general conference covering wide-ranging diplomatic matters – including naval. The Japanese, too came to the bargaining table on the hard reality that international power-balances were changing; and their own naval schemes were unaffordable.[46] This last was underscored by the point that, in 1921, naval expenditure absorbed 31 percent of Japan’s entire fiscal budget.[47]

A multi-national conference on all these matters was held from 12 November 1921 in Washington,[48] including plenary sessions in the Continental Memorial Hall on Seventeenth Street.[49] The result was a series of eight multi-party treaties covering all the major post-war international issues.[50] Of these, three were closely connected: the ‘Nine Power Treaty’ that dealt with western influence in China; the ‘Four Power Treaty’ that covered Pacific fortifications – an issue with clear implication for naval power – and the ‘Five Power Treaty’ on naval disarmament.[51] Although it was only one of the arrangements concluded in Washington, the ‘Five Power Treaty’ defined an immediate set of naval limitations, framed subsequent naval arrangements that dominated the inter-war period; and became generally known by the metonym ‘Washington Treaty’.[52]

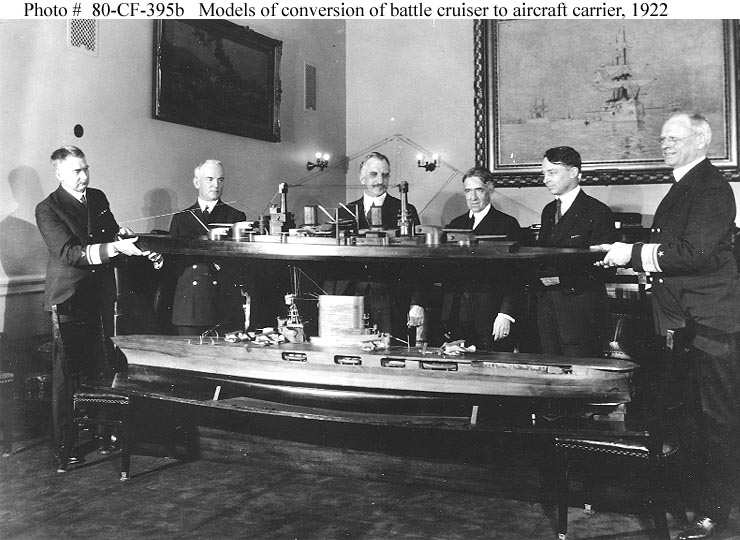

The result of the ‘Five Power Treaty’ for the United States was that much of the 1916 programme was cancelled, including the battlecruisers. Four of the Lexingtons, variously between 4 and 22.7 percent complete, were broken up on the stocks.[53] The remaining two were completed as aircraft carriers.[54] Yet here, too, as Ferreiro explained in his 2006 paper, Goodall had a significant influence on the aviation design.[55]

So the story of the American battlecruiser essentially came to an end. The next US Navy foray into fast but relatively lightly armoured heavy ships came in another war, with ships never formally classified as ‘battlecruisers’.[56] But that is another tale.

Meanwhile, for more on battlecruisers, check out my book The Battlecruiser New Zealand: A Gift to Empire. Click to buy.

About the author: Matthew Wright is a professional historian who has been extensively published by Penguin Random House, among others, has written many academic papers, and is best known for his international contribution to the study of military and naval history. Many of his books have been used as university texts. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society at University College, London. Visit him online at www.matthewwright.net

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2020

[1] Tony Gibbons, The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers, Salamander, London 1983, p.234.

[2] http://www.shipscribe.com/styles/S-584/images/s-file/s584102c.htm

[3] Ryan Peeks, ‘Battlecruisers in the United States and the United Kingdom 1902-1922’, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/b/battlecruisers-in-the-united-states-and-the-united-kingdom-1902-1922.html

[4] He was appointed Temporary Rear Admiral on 23 March and Temporary Vice-Admiral on 25 May 1917;

[5] The basis for development was ‘Design 169’, http://www.shipscribe.com/styles/S-584/images/s-file/s584102c.htm

[6] Ryan Alexander Peeks, ‘The Cavalry of the Fleet: Organisation, doctrine and battlecruisers in the United States and the United Kingdom, 1904-22, PhD thesis, University of North Carolina, 2015, p. 341

[7] Ibid, pp. 341-342.

[8] Larrie D. Ferreiro, ‘Goodall in America: the exchange engineer as vector in international technology transfer’, Comparative Technology Transfer and Society, Vol. , No. 2, August 2006, p. 179. See also D. K. Brown, Nelson to Vanguard: Warship Design and Development 1923 1945, Seaforth, Barnsley 2009, p. 9.

[9] http://www.shipscribe.com/styles/S-584/images/s-file/s584138c.htm

[10] Ferreiro, p. 180.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid, p. 179.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Peeks, p. 343.

[16] Ferreiro , p. 181.

[17] https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/s-file/S-584-137.html

[18] https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/s-file/S-584-135.html

[19] For tabular summary, see Peeks p. 345.

[20] Cited in Peeks, p. 347.

[21] Ferreiro, p. 183.

[22] Ibid.

[23] http://www.shipscribe.com/styles/S-584/images/s-file/s584145.jpg

[24] http://www.shipscribe.com/styles/S-584/images/s-file/s584145c.htm

[25] Sturton (ed), p. 177.

[26] Ibid.

[27] See, e.g. Gibbons, p. 234.

[28] Antony Preston, The World’s Worst Warships, Conway Maritime Press, London 2002, p. 97

[29] Gibbons, p. 234.

[30] J. David Rogers, ‘Development of the world’s fastest battleships’, https://web.mst.edu/~rogersda/american&military_history/World%27s%20Fastest%20Battleships.pdf p.2.

[31] Ibid, p.6

[32] Peeks, pp. 348-349.

[33] Robert C. Stern, The Battleship Holiday, Seaforth, Barnsley 2017, p. 87.

[34] Norman Friedman ‘How promise turned to disappointment’, Naval History Magazine, Vol. 30, No. 4, August 2016.

[35] Eugene Edward Beiriger, ‘Building a navy “Second to None”: the US Naval Act of 1916, American attitudes towards Great Britain, and the First World War’, British Journal for Military History, Vol. 3, Issue 3, June 2017, p. 27-28.

[36] Paul H. Silverstone, The New Navy 1883-1922, Routledge, New York 2006, p. 16.

[37] https://mises.org/library/forgotten-depression-1920

[38] Stern, p. 99.

[39] Ibid, pp. 98-99.

[40] NA CAB/23/23, ‘Cabinet 67(20), Conclusions of a meeting of the Cabinet, held at 10 Downing Street, S.W., on Wednesday, 8th December 1920, at 11.30 a.m.’.

[41] ADM 116/1831, Jellicoe to Admiralty, 26 June 1919

[42] Ibid, D of P to Jellicoe, 9 July 1919.

[43] Stern, p. 99.

[44] For discussion see Ira Klein, ‘Whitehall, Washington, and the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1919-1921’, Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 41, No. 4, 1972.

[45] Gordon Daniels, Janet Hunter, David Steeds and Ian Nish, ‘Studies in the Anglo-Japanese Alliance’ (1902-1923), London School of Economics Discussion Paper IS/03/443, London, 2003.

[46] Stern, p. 84.

[47] Justin Rohrer, ‘Arms control in dynamic situations: a study of the Washington Treaty system’, The Orator, Vol. 5, University of Washington 2010, p. 57.

[48] Quincy Wright, ‘The Washington Conference’ (1922), Minnesota Law Review, 2102.

[49] Quincy Wright, ‘Notes on International Affairs: the Washington Conference’, The American Political Science Review, Vol. 16, No. 2, May 1922, p. 285.

[50] Stern, p. 107

[51] Noted in Thomas G. Mitchell ‘New Washington Naval Conference could prevent a deadly South China Sea showdown’, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/new-washington-naval-conference-could-prevent-deadly-south-19757

[52] https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000002-0351.pdf Various qualifying sub-titles were also given at the time, associated with naval disarmament, by the different signatories in their official documentation reporting the treaty.

[53] Silverstone, p. 23.

[54] Stern, p. 107.

[55] Larrie D. Ferreiro , ‘Goodall in America: the exchange engineer as vector in international technology transfer’, Comparative Technology Transfer and Society, Vol. 4, No. 2, August 2006, pp. 187-188.

[56] Sturton (ed), p. 184.

Recent Comments