Mention HMS Hood and just one ship usually springs to mind. However, there was another HMS Hood, a battleship laid down for the Royal Navy in August 1889, which survived long enough to be given one last – and decisively final – role a few months after the outbreak of the First World War.[1]

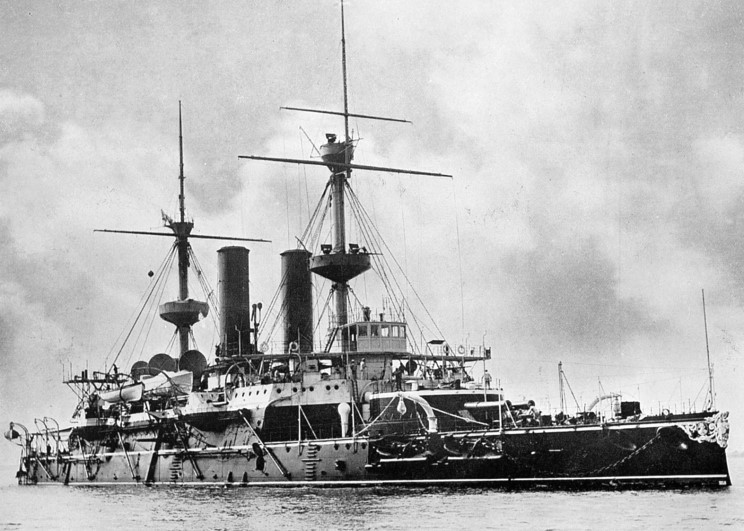

This earlier Hood was a curious mix of the old and new of her day. She was Britain’s last old-style turret ship and the Royal Navy’s last low-freeboard battleship. But in other ways she looked forward, incorporating engineering features that became standard in British battleships over the next decade,[2] largely developed by the Royal Navy’s talented Director of Naval Construction, Sir William Henry White (1845-1913).[3] He had, literally, written the book on naval design; his A Manual of Naval Architecture was over 600 pages long.[4]

By quirk of nomenclature, Hood was technically only Britain’s second new-build battleship. As we saw in an earlier article, the term derived from the age of sail and was in general use during the later nineteenth century to describe the largest warships. But it was not adopted by the Royal Navy as a formal classification until 1887,[5] when it was retroactively applied in three ‘classes’ to older armoured ships, and to the low-freeboard ships under construction.[6] The first new-build ‘first class’ battleship ordered under this classification system was the barbette-equipped Royal Sovereign. The second was the turret-equipped Hood.[7]

The reasons why Britain went for both a barbette and a turret design can be traced to the technical debates of the 1880s and tell us a good deal about period power-balances, both within the British Admiralty,[8] and outside it.[9] British battleships laid down from the late 1870s were limited to about 10,000 tons displacement for largely financial reasons.[10] That was problematic; gun sizes and weights were spiralling up, and so was the thickness of the armour needed to protect against such shells. One way of saving weight was to slash the freeboard, largely because it required less area of armour. By this time there were also two main ways of mounting the main armament. Barbettes mounted the guns on an open revolving platform atop a fixed armoured cylinder, were lighter than turrets, and could therefore be raised higher, partially compensating for low freeboard with its inevitable problems in heavier seas.[11] Conversely, turrets offered protection for the guns and their crews, but at the cost of top-weight.

The problem was that there was no recent battle experience, and the arguments otherwise seemed balanced. As a result, Britain’s 1880s-era battleships oscillated between both systems. The six low-freeboard ‘Admirals’ laid down between 1880 and 1883 were barbette ships. However, Britain’s 1884-85 program, the two Victoria class, were given two 16.25-inch breech loaders in a single massive turret forwards,[12] wedged into 10,470 tons.[13] More money was available for their successors under the 1886-87 program, the two Trafalgars. These reverted to a fore-and-aft turret layout on around 12,000 tons.[14] Low freeboard forced all these ships to slow in heavy seas and affected their ability to fight.[15] Increasing the freeboard required bigger ships, demanding political buy-in at a time when defence spending was limited, and when the threat of torpedo boats was used as an argument against funding heavier vessels.

The debate over turrets versus barbettes was not resolved in early 1888 when the lack of naval spending provoked intense public debate, another of the periodic ‘naval scares’ that marked the popular British response to the era when its Empire was at the zenith of its economic and political power. The outcome of this particular agitation has been subject of a good deal of discussion between historians, but recent work suggests that Britain’s Prime Minister, the Marquess of Salisbury, was essentially compelled to accept calls for increased budgets.[16]

The Naval Defence Act that followed in May 1889 initiated the ‘two power’ standard, by which the Royal Navy was equal to the next two strongest naval powers. This demanded a massive building program, including eight first-class and two second-class battleships.[17] The act also allocated funding equating to more money per ship. That made it possible to construct high-freeboard barbette ships, able to maintain speed and fight in most sea states. But a turret ship would still have to be low freeboard.[18] Like all such legislation the Act was developed over many months prior to it being passed, with advice from the Admiralty. A lengthy Board of Admiralty meeting at Devonport dockyard in August 1888 – as the legislation was under consideration – ended by specifying the main parameters of the first-class battleships.[19] Among other things, they were required to have four 13.5-inch/30 calibre guns[20] in two mountings, fore and aft, backed by 6-inch weapons.

White got the job of developing a ship to fit these particulars. He favoured high-freeboard barbette ships, but asked his team to produce various options with barbettes, turrets, armour schemes, speed, range and other characteristics.[21] In November the sketch designs were evaluated by a Committee comprising the Board of Admiralty and other officers. The First Naval Lord,[22] Admiral Sir Arthur Hood (1824-1901),[23] favoured turret ships; but the rest of the Committee were swung towards high-freeboard barbette ships by the ‘Report of the 1888 Manoeuvres Committee’, which highlighted the difficulties low-freeboard battleships had in a seaway.[24] The upshot was an agreement that one of the first three first-class battleships would be a turret ship. This eventually emerged as HMS Hood.

A good deal of mythology has since sprung up around Hood. One otherwise authoritative reference work states that she was named after the First Naval Lord who had pushed her.[25] This is not strictly so;[26] she formally commemorated his ancestor Admiral Sir Samuel Hood (1724-1816).[27] However, the name was still an obvious reference to Arthur Hood, and this link was unlikely to have been lost on the Board.[28] Royal approval was required for any ship name;[29] and we could speculate that Queen Victoria might have been suitably amused by the connection.

More crucially, various reference books also refer to Hood as a modified Royal Sovereign design, cut down a deck to compensate for the turrets. In fact the two were different designs. The starting point for what eventually became Royal Sovereign was an improved ‘Admiral’, while what emerged as Hood began originally as an improved Trafalgar.[30] These were the springboards for the multiple sketch designs for possible barbette and turret ships noted earlier. And the two sketches selected for construction by the Committee in November 1888 were distinct: a 13,650 ton low-freeboard turret ship dubbed ‘C’; and an 11,600 ton high-freeboard barbette design dubbed ‘c’.[31]

White handed the barbette ship for development to his assistant Beaton, and the turret ship to W. H. Whiting, the Constructor, with instructions that they should work closely together.[32] He had direct personal oversight of both. The result was that the final designs had much in common. Their propulsion plants were virtually identical, and so were many elements of detail, equipment and general design. At the urging of Captain John Fisher, the Director of Naval Ordnance,[33] the secondary armament for both was switched to new-design quick-firing 6-inch/40 calibre guns, though these were still under development.[34]

For all that, Hood and Royal Sovereign were still separate designs, prepared in parallel, and with features of their own. Things could not be otherwise. Stability considerations alone meant their weight distributions had to be separately calculated. Final design displacement differed substantially: Royal Sovereign’s legend displacement as built was 14,150 tons and Hood’s 14,780.[35] The later Royal Sovereigns were heavier, but still not as heavy as Hood.[36] One variation was in the armour systems. White was concerned that Hood’s ship-movement characteristics might leave her main armament vulnerable to deck hits during a roll – not usually a problem at the expected battle ranges and shell descent angles of the late 1880s. He developed answers unique to that issue.[37]

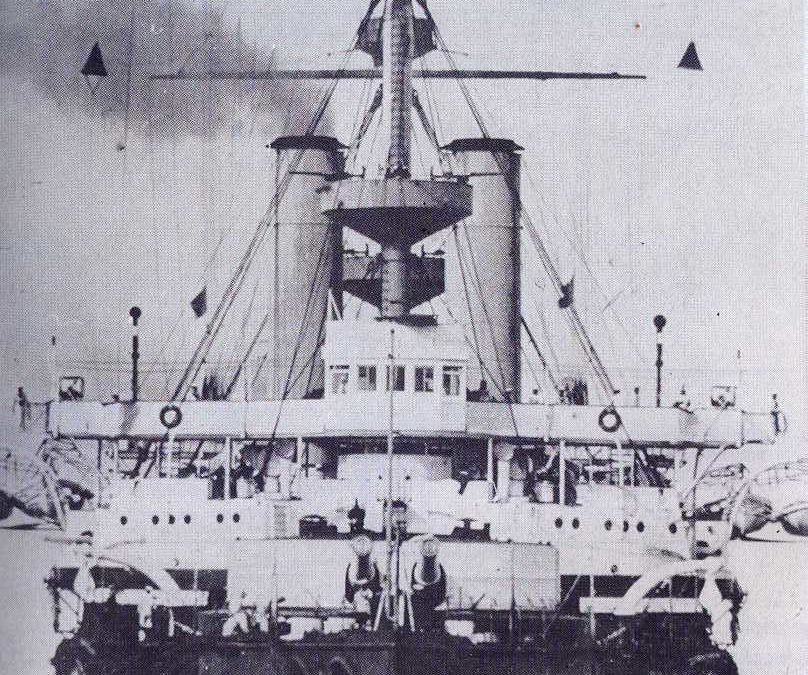

Hood was laid down at Chatham dockyard in August 1889 and launched in July 1891, completing in June 1893, for a cost of £849,242.[38] She was already obsolescent; apart from anything else, the turret-versus-barbette debate in Britain was resolved during the years Hood took to build. Harvey-process face-hardened armour offered the same protection as older compound armour on lower weight, and was introduced in limited quantities in the two second-class battleships authorised in the 1889 Act. The pair were also fitted with backless shields over their barbette-mounted main armament.[39]

Harvey armour was more extensively used in the second-class battleship HMS Renown, designed during 1892,[40] and in the nine first-class battleships of the 1893-94 programme. This released weight that could be devoted to armoured gun-houses atop the barbettes, lighter than old-style turrets but offering similar protection, all without pushing the scale of the ships beyond what could be first financed and then supported with available infrastructure, notably docks. These new-style mountings were soon called ‘turrets’, although they were quite different from the older variety fitted to Hood.[41]

These developments were well under way by June 1893 as Hood made her first deployment to the Mediterranean.[42] She served with the Mediterranean Fleet until April 1900, then returned to Chatham where she paid off into reserve. She was back in the Mediterranean fleet by the end of 1901.

Thanks to her low freeboard, Hood was not as a good a sea-boat as the Royal Sovereigns and could not maintain speed in a seaway.[43] Plans floated in 1902 to update her with modern 12-inch guns foundered on the cost of some £208,000,[44] over a fifth of that needed for a new battleship. Hood instead commissioned into the Home Fleet in 1903, and entered the reserves in 1905. She was put on the disposal list in 1911, but had yet to be offered for scrap when, in 1913-14, she was used as a test bed for anti-torpedo bulges, then a closely guarded secret.[45]

Hood was finally offered for sale to the breakers in August 1914. But she remained to be sold in November, when she was given a final duty, scuttled to block the entrance to Portland Harbour’s South Channel, as a hedge against U-boat attack. The effort did not go well. Hood took a while to go down from the effects of opened seacocks alone, and explosives had to be used to sink her before the tide dragged her too far. As a result she rolled to port and sank upside down.[46] She was subsequently nicknamed the ‘old hole in the wall’[47] and later became a diving attraction.

There is post-script. Hood’s ship’s bell was removed before the scuttling, and in 1918 the widow of Rear-Admiral Sir Horace Hood, who died in the Battle of Jutland, gave the bell to the battlecruiser HMS Hood, under construction. It went down with that ship on 24 May 1941. In August 2015 the bell was retrieved from the wreck,[48] and placed in the National Museum of the Royal Navy as a memorial to those lost on the battlecruiser.[49]

This was the story of one of Britain’s first officially-classified battleships. For the politics and engineering behind their last battleships, check out Britain’s Last Battleships. Click to buy.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2019

Notes

[1] R. A. Burt, British Battleships 1889-1904, New Revised Edition, Seaforth 2013, p. 103.

[2] Noted in Eric Grove, ‘The battleship Dreadnought: technological, economic and strategic contexts’, in Robert J. Blyth, Andrew Lambert and Jan Ruger (eds), The Dreadnought and the Edwardian Age, National Maritime Museum, Surrey 2011, p. 167.

[3] Fred M. Walker, Ships and shipbuilders: pioneers of design and construction, Seaforth, Barnsley, 2010, pp. 164-165.

[4] William Henry White, A Manual of Naval Architecture, John Murray, London 1877.

[5] Grove, p. 166.

[6] Victoria, Sans Pariel, Trafalgar and Nile.

[7] Burt, p. 90 gives timing for Royal Sovereign.

[8] For discussion of the political aspects of White’s career, see Don Leggett, ‘Naval architecture, expertise and navigating authority in the British Admiralty, c.1885-1906, Journal for Maritime Research, 16:1, pp. 73-88, May 2014, esp. pp. 78-79.

[9] For details see Robert E. Mullins (ed John Beeler), The Transformation of British and American Naval Policy in the pre-Dreadnought Era, Palgrave Macmillan, Chevy Chase, 2016.

[10] Norman Friedman, British Battleships of the Victorian Era, Seaforth, Barnsley 2018, p. 191.

[11] For period discussion see Thomas Brassey, The British Navy, Its Strength, Resources and Administration, Vol 1, Longmans, Green & Co, London 1882, p. 284.

[12] Friedman, pp. 198-204.

[13] Figure from Tony Gibbons, The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers, Lansdowne Press, London 1983, p. 120.

[14] Friedman, pp. 204-209.

[15] Burt, p. 70.

[16] Mullins, pp. 69-70.

[17] There is a summary in Eric J. Grove, The Royal Navy since 1815: a new short history, Palgrave MacMillan, Basingstoke 2005, pp 74-78.

[18] Noted in Burt, p. 69.

[19] Burt, p. 68.

[20] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_135-30_mk1.php

[21] Burt, p. 68.

[22] This post was shortly redubbed ‘First Sea Lord’.

[23] https://www.geni.com/people/Arthur-Hood-1st-Baron-Hood-of-Avalon/6000000016445437650

[24] Burt, p. 70; Friedman, p. 232.

[25] Burt, p. 101, states that the ship was named after Sir Arthur Hood.

[26] Friedman, p. 234.

[27] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Samuel-Hood-1st-Viscount-Hood

[28] Implicitly noted by Friedman, p. 234.

[29] This was usually a formality, however King George V declined names proposed by Winston Churchill in 1912.

[30] Friedman, p. 228, 234.

[31] Roll issues noted in Burt, p. 69.

[32] Ibid, pp. 70-71.

[33] Ruddock F. Mackay, Fisher of Kilverstone, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1973, p. 193.

[34] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_135-30_mk1.php

[35] Burt, pp. 73, 103.

[36] Ibid, p. 73.

[37] Friedman, p. 234.

[38] Burt, p. 103.

[39] Ibid, p. 114.

[40] Friedman, p. 250. She was completed in 1895.

[41] Noted in Burt, p. 102.

[42] Summarised here: https://navalinstitute.com.au/22-june-1893-tryon-and-hms-victoria-collision-with-hms-camperdown/

[43] Burt, p. 103.

[44] Friedman, p. 239.

[45] Burt, p. 108.

[46] Noted in https://www.bevs.org/diving/wkhood.htm

[47] Burt, p. 108.

[48] https://newatlas.com/paul-allen-bell-hms-hood/38837/

[49] https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3607165/Remembering-HMS-Hood-Bell-battlecruiser-sunk-75-years-ago-Royal-Navy-s-biggest-disaster-retrieved-seabed-Microsoft-founder-Paul-Allen-formally-unveiled-Princess-Royal.html

Recent Comments