The Battle of the River Plate is one of the best known encounters of the Second World War. It was the first major sea battle of that conflict, and it came on 13 December 1939, a time when the so-called ‘phony war’ was in full swing – the brief period when the Second World War seemed not to be turning into a serious ground conflict. Involving the famous armoured cruiser Graf Spee , this engagement shared many similarities to the pursuit of the Goeben , a German battlecruiser from the First World War.

The Battle of the River Plate threw the focus on the war at sea, where the Panzerschiffe (Armoured ship) Admiral Graf Spee had been despatched to raid merchant shipping. All went well for them until her commander, Hans Langsdorff, decided to strike the trade around the River Plate and was caught by a small British squadron under Commodore Henry Harwood that consisted of two light cruisers – including one from the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy – and the ‘B’-type heavy cruiser Exeter. Although all three were faster than Graf Spee, the German 11.1-inch guns outranged theirs and could easily penetrate the British armour at expected battle ranges, whereas only the six 8-inch guns of Exeter were likely to be effective against the German ship’s vitals.

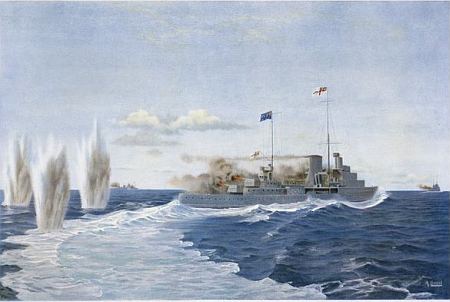

HMS Achilles of the New Zealand Naval Division at the Battle of River Plate, 13 December 1939. Artwork by John Lloyd. Lloyd, Arthur John, b 1884. Lloyd, Arthur John, b. 1884 :New Zealand’s flag flies in the first naval battle of the war; H M S Achilles by skilful handling evades the shells of the Admiral Graf Spee [Auckland; 1940]. Ref: C-055-004. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23233527

In the struggle that followed Exeter was severely mauled and the light cruisers damaged. Damage done to Graf Spee included the loss of her fuel processing system, desalinator and galley facilities – serious enough to cause Langsdorff to make for a harbour. He chose Montevideo, in Uruguay, as opposed to Mar del Plata in Argentina.

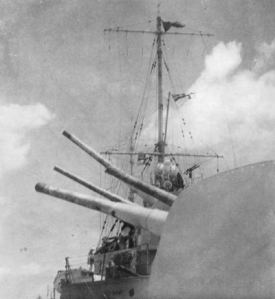

Achilles’ aft turrets after the battle, with blistered paint from the heat of firing. I’ve put my hand on Y-turret, foreground – it’s preserved at the Devonport naval base. Public domain, New Zealand Electronic Text Centre http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/WH2-1Epi-fig-WH2-1Epi-b013a.html

Exeter limped back to the Falklands while the two light cruisers waited offshore. Uruguay was neutral and, by international law, belligerents were meant to stay no more than 24 hours. Langsdorff insisted he needed two weeks to make repairs, but in an atmosphere of increasing diplomatic tension and subterfuge was given just 72 hours. The only reinforcement Harwood could get in that time was the heavy cruiser Cumberland; heavier forces were days off, suggesting that a repeat of the earlier battle might follow. In the event, Langsdorff put to sea and – as soon as he was in international waters – scuttled his ship.

The real question is why Harwood attacked in the first place. Graf Spee had, in theory, been designed to defeat any cruiser and on paper the odds were against his squadron. He could have ‘shadowed’ the Germans until heavier British forces arrived. Part of his motive was the long tradition of the Royal Navy – a service buoyed on Nelson-era tradition whose commanders didn’t hesitate to seek out the enemy, whatever the odds. From the tactical viewpoint, he did not have to sink Graf Spee; all he had to do was damage her enough to require dockyard repair, which was not going to be easy for the Germans to achieve in the South Atlantic. And even if Graf Spee sank his entire squadron, the loss of three cruisers was not going to destroy Royal Navy superiority at sea, whereas the proportionate loss to Germany of the Graf Spee as a raider – even if only damaged – was much greater.

However, another reason harked back to similar circumstance at the beginning of the previous war. In early August 1914, the German battlecruiser Goeben and light cruiser Breslau were in the Mediterranean as war clouds loomed. British forces included two battlecruisers, along with a squadron of four armoured cruisers – Defence, Warrior, Black Prince and Duke of Edinburgh – under Rear-Admiral Ernest Troubridge (1862-1926). The battlecruisers ran into the German squadron heading east, but could do nothing because war hadn’t yet been declared. However, Indomitable wrongly reported that the German force was moving at 26-27 knots. Both British battlecruisers had foul hulls and their peace-time complement of stokers, meaning they were not able to develop full speed.

When war broke out, only Troubridge’s force was in a position to intercept, and the problem was that although he had Britain’s four most powerful armoured cruisers, two light cruisers and several destroyers, Goeben was a battlecruiser with ten 11.1-inch guns, out-ranging his own 9.2 and 7.5-inch pieces, and able to penetrate the British armour. Goeben was also faster on paper, a speed that Indomitable‘s report seemed to endorse. In fact, Goeben had aborted boiler repairs in Austria when war clouds loomed – and had averaged just 22.5 knots in previous hours, possibly peaking at 24.

HMS Minotaur (1906) with her original short funnels. Public domain.

Troubridge still intended to engage, hoping for a night action where he might get within range of his own guns without being too badly hit on the way in. However, this was not possible, and around 3.30 am on 7 August was apparently persuaded by his Flag Captain, Fawcet Wray, not to engage in daylight. Goeben and Breslau escaped to Turkey. A Court of Enquiry, convened in September, decided to courtmartial Troubridge. Among other things, it turned out that the Admiralty had ordered Berkleley Milne, Commander in Chief of British naval forces in the Mediterranean, to decline engagement with superior forces until reinforcements could be sent from Britain. Troubridge had also been tasked with enforcing the blockade of the Adriatic. Although there was some thought that the ‘superior forces’ referred to the Austrian fleet, both orders gave Troubridge an out.

However, the defence also revolved around whether a battlecruiser – specifically designed to overwhelm armoured cruisers – could have been engaged by four such ships and still won. The consensus was that Goeben would have prevailed. Troubridge was honourably acquitted; but there was disagreement with that verdict in the service and the incident effectively brought an end to his career. He was reduced to half-pay and in 1916 sent as liaison officer to Serbia. Testimony in 1919 confirmed that his reputation had, basically, been destroyed.

That was well known to Harwood as he led his own cruisers towards Graf Spee 25 years later. And everybody knew what his decision to engage meant within the service. Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, the First Sea Lord, told Harwood that ‘even if all our ships had been sunk, you would have done the right thing. Your action has reversed the findings of the Troubridge courtmartial and shows how wrong it was’.

For the full tale of Achilles’ remarkable experience during the Battle of the River Plate, check out my book Blue Water Kiwis, available on Amazon. Click to buy.

You can also read more of my articles:

Is the Submarine the Perfect Stealth Warship?

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2018

Recent Comments