In many the 1890s were the high noontide of Britain’s globe-spanning Empire. It was also when they suffered their worst naval disaster of the late nineteenth century with the sinking of HMS Victoria – and it occurred not as a dramatic outcome of some storm or foreign action, but as what amounted to an embarrassing failure to manoeuvre, for one reason or another.

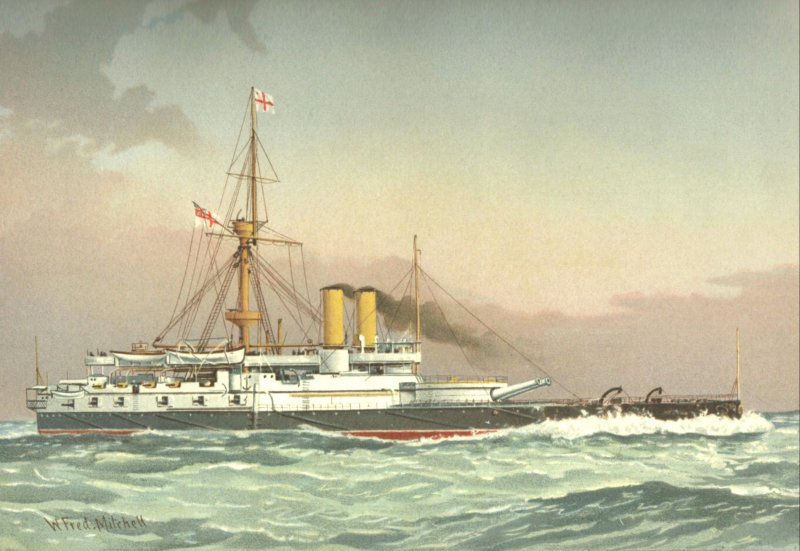

The catastrophe unfolded in June 1893 when the Mediterranean Fleet – eleven battleships and three cruisers – arrived off Tripoli in two lines. The fleet was under command of Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon, flying his flag in Victoria. This was an unusual battleship, with her sister Sans Pariel arguably one of the ugliest battleships of the period. Her origins are explored in an earlier article. Perhaps the oddest part of the design was that her two big guns were carried in a huge turret forwards, all on low freeboard.

Tryon had long chafed at the nature of Royal Navy fleet command, in which orders for particular manoeuvres came from the top and were individually acknowledged. He felt this stifled initiative. His replacement was a system he dubbed ‘TA’, in which captains followed the next ship and were expected to complete skeletal instructions.

The Mediterranean fleet was not following his TA system on that fateful June day, but Tryon’s commanders knew his mind-set, and he had generally discussed the manoeuvre he wanted with his captains. Ship-board life continued: it was ‘make and mend’ afternoon, when the crew attended to duties such as laundry or patching clothes. The day was stifling hot, and every hatch on the Victoria was open in an effort to get air flowing. As the two columns drew up to the Lebanese coast, at 3.28 pm, Tryon ordered that the two divisions turn sixteen points (180 degrees) inwards, preserving the order of the fleet.

The problem was that to do that they had to be at least 2000 yards apart, but Tryon had earlier ordered them to close up to 1000. That rendered the order nonsensical – all it would do was bring the two columns into collision. That raised eyebrows on the bridge of the battleship leading the second column, HMS Camperdown, flagship of Rear-Admiral Alfred Markham. He delayed execution; so Tryon signalled: ‘what are you waiting for?’ Markham accordingly went ahead.

The columns were moving at a little over 8 knots, and the disaster unfolded in what amounted to slow motion; it took nearly two minutes from the point where the turn began to the collision occurring. Even so, nobody reacted until a catastrophe was obvious. An order went out, just 60 seconds before the collision, to close the watertight doors.[1] Little could be done to scrub off momentum, however; and aboard Camperdown – thanks to a mix-up between bridge and engine room – the engines were only ordered to 3/4 reverse power.

The results were disastrous. Camperdown – still moving at a speed estimated by witnesses at anything between 4 and 6 knots – crashed into Victoria some 65 feet from her stem, at an angle of about 80 degrees. The DNC, William White, later calculated that the speed – based on the engine revolutions and speed loss from the turn – had to be about 6 knots.[2] Victoria was moving at 5 or 6 knots – a figure also calculated later by White – and the impact rotated her 60 feet sideways. Camperdown was stopped by the rigidity of Victoria’s armoured deck; but the damage was compounded by Camperdown‘s ram, which penetrated 9 feet, ripping a hole below Victoria‘s armoured deck that was further widened to perhaps 100 square feet as the ships rotated. They remained locked for two minutes; then Camperdown began backing away.[3]

The extent of damage was initially not obvious. However Tryon, who had been involved with design debates over Victoria when he was Permanent Secretary of the Admiralty,[4] was well aware of the citadel system and the extensive compartmentalisation designed into his vessel. He initially did not think Victoria would sink, and ordered the fleet not to lower boats. Then he instructed his flag captain, Maurice Bourke, to beach her. Meanwhile a damage control party tried to wrestle a collision mat into place – a large sheet of canvas to partially plug the underwater damage – and the crew scrabbled to close the watertight doors. That was easier said than done. All of them were manually operated and took time to individually close, and some could not be reached. Others were only half-closed before rising water sent the men fleeing for their lives. Nor could the collision mat be placed.

Later estimates suggested that the ship took on 680 tons of water in the two minutes before Camperdown pulled clear, even though Camperdown’s bow and ram partially closed the hole. This was a significant loss of buoyancy for a ship of 10,470 tons, particularly forward where the combination of heavy turret and low freeboard left little reserve. After Camperdown pulled clear, water simply poured into the ship. The rate of flooding, it transpired later, was limited by the rate at which compartments could fill through available openings, such as leaking or open watertight doors. Without the subdivision, White calculated, Victoria would have taken on 3,000 tons of water a minute.[5] The actual rate was less; but this was still largely academic. ‘Even when thus checked,’ White wrote, ‘the evidence clearly shows that a very large weight of water found its way into the interior, and passed for a considerable distance fore and aft in a very short time.’[6]

The results were devastating. After four minutes the ship was listing to starboard and the bow had dropped 10 feet, sending water through the hawse-pipes into the upper deck. Within five minutes the water was over the foredeck and had reached the turret, where it began rushing through the gun ports.[7] Flooding boundaries could not be established, and after eight minutes it was clear Victoria was sinking.

Meanwhile the fleet was thrown into chaos because they were playing follow-my-leader – and Victoria and Camperdown blocked the way. There was a scrabble to avoid a succession of collisions. HMS Nile – next in line – came close to hitting Victoria. Ships further back frantically slewed to port and starboard, propellors threshed, and the entire Mediterranean Fleet – the symbol of Britain’s naval prestige – was thrown into confusion, with Victoria sinking in the middle of the chaos.

Victoria‘s commander, John Jellicoe, was sick with a fever of 103 degrees, but went on deck to get the boats hoisted. Bourke ordered abandon ship; but just 13 minutes after impact, equipment began falling to starboard with sounds audible from HMS Nile. By now water was pouring into the starboard 6-inch gun ports amidships. Tryon climbed to the top of the chart-house and – according to the courtmartial evidence afterwards – was heard to murmur something like: ‘it was all my fault’. Witnesses varied on the actual wording.

Suddenly the Victoria lurched to starboard and rolled over. Jellicoe recalled the moment:

I said to Lieutenant [Arthur] Leveson ‘we had better go down the side of the ship as she turns over’, and we started to walk down the port side, which by that time was horizontal. I had just reached the jackstay of the torpedo nets in line with the upper deck when the ship turned bottom up…when I found myself under water [I] let go and started to rise to the surface…I felt the suction of her sinking but was not drawn down.[8]

The ship went down bow-first, her propellors still spinning, leaving survivors dotting the water. Some 358 men died; and 173 of the survivors were injured. Camperdown, too, took severe damage, and it was only through rapid work by her crew that she did not follow the flagship to the bottom. Victoria, meanwhile, descended bow-first. When the wreck was discovered in 2004 it was found to have penetrated 30 yards into the mud, standing vertically.

Inevitably there was a scrabble to find out what had happened. Victoria had been built as a ‘citadel’ ship; she wasn’t meant to sink after being holed so far forwards. Were all Britain’s battleships eggshells waiting to be taken out by French torpedo-boats? That was the worry as an enquiry opened in which both Markham’s head, and that of Bourke as the captain of the Victoria, essentially stood on the chopping block. We shall cover that in the next article.

For more on Britain’s battleships, remember to check out my book Britain’s Last Battleships.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2019

Notes

[1] William H. White, ‘Report by the Assistant Controller and Director of Naval Construction, Based Upon Minutes of Proceedings of the Court Martial Appointed to Inquire into the Loss of Her Majesty’s Ship “Victoria”’, 15 September 1893, at http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/Report_on_the_Loss_of_H.M.S._Victoria, accessed 28 August 2019

[2] William H. White, ‘Report by the Assistant Controller and Director of Naval Construction, Based Upon Minutes of Proceedings of the Court Martial Appointed to Inquire into the Loss of Her Majesty’s Ship “Victoria”’, 15 September 1893, at http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/Report_on_the_Loss_of_H.M.S._Victoria, accessed 28 August 2019.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Friedman, p. 204.

[5] William H. White, ‘Report by the Assistant Controller and Director of Naval Construction, Based Upon Minutes of Proceedings of the Court Martial Appointed to Inquire into the Loss of Her Majesty’s Ship “Victoria”’, 15 September 1893, at http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/Report_on_the_Loss_of_H.M.S._Victoria, accessed 28 August 2019.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Cited in Reginald Bacon, The Life of John Rushworth, Earl Jellicoe, Cassell & Co, London 1936, p. 65.