As war clouds loomed over Europe in the late 1930s, Britain’s last generation of battleships were well in hand. By 1938 the five King George V class were under construction and the first two examples of their successors, the Lions, were due to be laid down in 1939.[1]

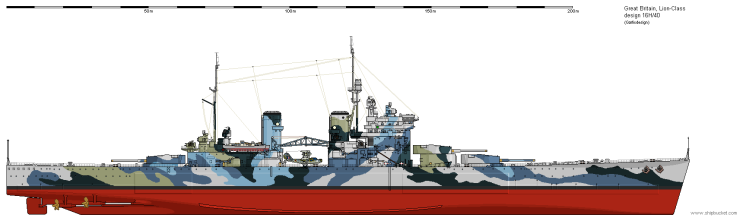

The Lion was the fastest battleship developed by Britain to that time, with a main armament of new-style 16-inch guns that were superior to the Mk I 16-inch weapons fitted to the Nelson class of the 1920s. The overall design was not as large as the equivalent US ships, the Iowa class, but was the largest Britain could both build and then support in service. The specific details of it emerged from the interaction between British industrial and infrastructure limitations and the break-down of the inter-war naval treaty system.[2] As we saw in the previous article, a protocol negotiated during 1938 increased the agreed limit on standard battleship displacement to 45,000 tons.[3] This was a step up from the 35,000 tons of the Second London Naval Treaty.[4] However, the British could not build to the new limit for financial, industrial and infrastructure reasons,[5] so the 1938 Lions were not far over 40,000 tons.[6] Despite a jump in size and fire-power, however, they were conceptually related to the preceding King George V’s. Although mounting nine Mk II 16-inch guns,[7] they had a similar protection scheme and were not radically faster.[8] This sort of relationship between successive designs was not unusual.[9]

HMS Lion, pictured if completed to the modified design 16H of 1940. Credit: Garlicdesign, via Shipbucket http://www.shipbucket.com/drawings/7659, Creative Commons 4.0 non-commercial license.

Two Lion class battleships – Lion and Temeraire – were authorised under the 1938 programme for laying down in 1939.[10] Two more – Thunderer and Conqueror – were projected for the 1939 programme, to be laid down in 1940. How they might have matched up to, for instance, Germany’s contemporary ‘H’ class battleships is difficult to say; in general terms they were lighter, but otherwise comparable. In point of fact, direct comparison with ships of other nations is difficult because the staff requirements and design philosophies of the various naval powers varied, leading to differences in engineering outcome. The British, for example, re-adopted heavy vertical side armour because – among other things – it improved reserve buoyancy, offered better protection against shell splinters passing below the system in a sea-way than sloped internal armour, and was easier to repair. However, it also carried a significant weight penalty by comparison with the sloped internal side armour used by US Navy designers. The British also had specific requirements for dimensions, draft, performance in certain water temperatures and states of hull-fouling (time out of dock), and so on, which affected the specific details of the designs. In general, though, the Lions were broadly comparable to any of the other battleships of the same generation, outside the Japanese super-battleships.

However, war intervened, and how many of this class might ultimately have been built is speculative. Up to six were projected,[11] but of the four authorised, only three were ordered and two laid down before war brought all to a halt.[12] Yard number 567, which was assigned to the fourth ship Conqueror, was used instead for Vanguard.[13]

This aside, by early 1939 the Admiralty felt the new battleships they had in hand so far were insufficient to match the projected strengths of Japan, Germany and Italy.[14] The challenge, aside from the financial constraints, was building more without the delays needed to build heavy gun mountings.[15] National annual capacity was seven triple 16-inch mountings.[16] It was possible to expand that to ten, allowing a third 16-inch ship in the 1940 programme, but to do that the old facility at the Harland and Wolff Scotstoun Ordnance Works was going to have to be refurbished.[17] However, there were other options. The idea of a new ship using four old 15-inch mountings in storage had been floated in 1937.[18] Now it resurfaced; and to add weight to the idea, additional 15-inch mountings were going to become available as the Revenge class battleships were scrapped.[19]

As projected in 1939, a 15-inch gun ship could be laid down for the 1940-41 programme without compromising the Lions.[20] There seemed potential for such a ship in the Far East,[21] and there was talk of selling her to Australia.[22] The DNC’s department prepared plans for a 40,000 ton vessel with similar protection to King George V,[23] but which was otherwise broadly a four-turret edition of the 1938 Lion, with much the same transom stern, secondary and anti-aircraft armament, aviation facilities, and similar superstructure.[24] This was unsurprising: a good deal of work had gone into optimising the Lions and there was no need to re-invent the wheel. By mid-July the DNC had three options to hand, one of which, 15C, repeated Lion’s machinery.[25]

Detail of the 5.25-inch DP guns fitted to HMS King George V, also intended for the Lions and Vanguard. They were also fitted to a series of anti-aircraft cruisers produced in two sub-classes. Public domain, via Wikipedia.

War did not take long to disrupt things. A week after war broke out the DNC’s Department was moved to Bath, a spa town well to the west of London. This was to free up office space in Whitehall for operational staff,[26] but it took the DNC out of direct contact with the Admiralty. Design work on the 15-inch battleship was disrupted. Then, on 3 October, the two Lions were suspended.[27] So too, briefly, was work on the King George V class battleship Howe,[28] although it was resumed and she was launched on 9 April 1940.[29] Work on the Lion and Temeraire also resumed, but by the time they were again halted in May 1940 only some 218 tons of steel had been assembled for Lion and 121 for Temeraire. [30]

This was not the end of the Lion class; but for a while attention focused on the war. Nobody knew how it might develop, and during late 1939 the main activity was at sea. Late that year the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill,[31] picked up the idea of using the old 15-inch mountings from a remark by the Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, Rear-Admiral Tom Phillips.[32] In early December, Churchill asked for a ship of what he called the ‘battleship-cruiser type’ using these weapons, ‘heavily armoured and absolutely proof against air attack’.[33] As a result the Admiralty continued developing the 15-inch evolution of the Lion.[34] This ship – Vanguard – was projected under the 1940 Emergency War Programme,[35] and added in March that year.[36] Further work altered the oil capacity, and new designs were approved in May.[37] The relationship with Lion, apart from armament, was very close, and the Admiralty had not lost hope of building the Lions. That was underscored in September 1940, when the Vice Chief of Naval Staff became concerned about draft in both Lion and Vanguard, which restricted harbour access. This led to ‘Design 15E/1940’ for Vanguard, with a beam of 108 feet.[38] The side armour had to be thinned, partly to offset the weight of additional deck armour needed for increased beam. However, standard displacement rose to 41,900 tons with deep load of 47,500.[39]

Vanguard was formally ordered in mid-March 1941,[40] and plans were delivered to ship-builder John Brown & Co. ten days later.[41] The Lions remained in abeyance and had lost support at political level: that week Churchill – now Prime Minister and Minister of Defence[42] – urged that the remaining King George V’s should be completed ‘at full speed’ and that Vanguard, ‘the only capital ship which can reach us in 1943 and before 1945’ was ‘most desirable’.[43] There was no place for the Lions, and Vanguard’s new plans were approved by the Board of Admiralty in mid-April 1941.[44]

Such decisions reflected war needs. However, the Admiralty had not lost hope and continued to develop the Lions, largely on the basis of work done on Vanguard, underscoring the relationship between the two designs. Churchill remained personally interested despite having to bow to the wider realities of Britain’s industrial position, urging a Nelson style (main armament forward) layout for Lion because he imagined the midships hangar made the ship vulnerable.[45] This reflected a misconception he had about the King George V’s, which had the same hangar layout. He was wrong: as the First Sea Lord, Sir Dudley Pound, pointed out, the ‘aircraft hangars in the King George V class did not weaken the citadel. This had to include protection for the machinery spaces, which was enormously increased in these ships as compared with the Nelsons’.[46] Vanguard, whose design had much the same hangar and protection scheme at the time, was implicitly included in the debate.[47]

HMS Temeraire, second of the Lion class, as she might have appeared in 1945 with wartime-style modifications. Credit: Garlicdesign, via Shipbucket http://www.shipbucket.com/drawings/7661, CC 4.0 non-commercial license.

Many of the ideas applied to Vanguard were included in revised plans for Lion approved in 1942, further underscoring how the designs and thinking around them were entwined. Design work also got under way on improved 16-inch guns, coalescing eventually around the Mk IV design, which could handle higher barrel pressures and longer shells. However, official priorities focused on light aircraft carriers, some of which were ordered for construction at the Vickers Walker facility contracted for Lion. Even if materials and labour were available, that would have delayed Lion until at least 1944.[48] Then, in April 1943, the two ships in the class still authorised – Lion and Temeraire – were formally cancelled.[49]

The result was that once HMS Howe, last of the King George V class, was completed on 20 August 1942,[50] Vanguard became the sole British battleship under construction. The Admiralty still hoped to build the Lions, and design work continued on the basis of war lessons. The rising pre-eminence of aircraft intruded on occasion, including via one option for a hybrid battleship-carrier[51] – but all construction rested on re-authorisation. By 1944-45 the Lions had evolved into a vastly heavier vessel on the basis of war lessons. The DNC, Charles Lillicrap, felt that even this was going to be vulnerable to air attack. Plans were then floated for a cut-down version with a six-gun main armament. However, although the Admiralty proposed evolved Lion-class battleships for the 1945 programme,[52] they were rejected in October that year.[53] So ended the Lion class – a long, slow and painful death for a concept that, if it had gone ahead as intended in 1938-39, would have produced the most powerful battleships ever built by Britain.

There was still a pro-battleship lobby in the Admiralty,[54] and designs for 16-inch heavy gun mountings were still being contemplated as late as March 1949.[55] Nor was the death of the Lion the last word in British battleship construction: Vanguard was actually completed, and we pick up the story of Britain’s very last battleship in the next article.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2018

Notes

[1] William H. Garzke and Robert O. Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, Jane’s Publishing Company, London 1980, p. 263.

[2] See previous article and sources.

[3] ‘Limitation of Naval Armament: protocol signed at London, June 30 1938, modifying treaty of March 25, 1936’, https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000003-0523.pdf

[4] See Naval Limitation Treaty (Second London Naval Treaty) of 25 March 1936, Part 2 Article 4 (2), see text at https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000003-0257.pdf

[5] Norman Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, Seaforth, Barnsley, 2015, p. 329.

[6] July and June respectively, see Garzke and Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, p. 263.

[7] For details see http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_16-45_mk2.php

[8] Design 30 kt (Lion) vs 28 (King George V), Ian Sturton (ed) Conway’s All The World’s Battleships, Conway Maritime Press, London 1987, pp. 93 and 98.

[9] Compare, e.g. the Orion (1909 programme), King George V (1910 programme) and Iron Duke (1911 programme) classes, see Sturton (ed), pp. 60-61, 66, 68-69.

[10] July and June respectively, see Garzke and Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, p. 263.

[11] Raven and Roberts, p. 325.

[12] H. T. Lenton, British and Empire Warships of the Second World War, Naval Institute Press, 1998,

[13] Ian Buxton and Ian Johnston, The Battleship Builders: constructing and arming British capital ships, Seaforth, Barnsley, 2013, p. 69.

[14] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 336.

[15] Ibid.

[16] The implication was that two ships used up six of the mountings, meaning a third ship could be laid down every third year using the seventh mounting built in the three consecutive prior years; but that was too slow for the war emergency, and other limitations included labour force availability and armour steel production, which by 1939 had already held up the King George V class.

[17] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 407, n. 25.

[18] Ibid, p. 336.

[19] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 336. The official class name was Revenge, not Royal Sovereign, Sturton (ed) p. 77.

[20] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 336.

[21] Britain’s ‘Far Eastern’ ships, since the late nineteenth century, had always been lesser editions of the ships thought necessary for European waters; see part 3 of this article for further discussion.

[22] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 336.

[23] Against the 16-inch guns of the Nelson class the immunity zone was calculated as between 16,500 to 33,250 yards. Garzke and Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, p. 231.

[24] Reproduced in Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 337.

[25] Ibid.

[26] R. J. Daniel, The End of an Era, Periscope Publishing, Penzance, 2003, p. 10.

[27] Sturton (ed), p. 98.

[28] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 407, n.27.

[29] Garzke and Dulin, p. 224.

[30] Sturton (ed), p. 98.

[31] https://www.winstonchurchill.org/resources/reference/churchills-political-offices-1906-1955/

[32] http://www.naval-history.net/xGW-RNOrganisation1939-45.htm#12 – note that Phillips drowned when Prince of Wales was sunk in December 1941.

[33] First Lord to Controller and others, 3 December 1939, in Winston Churchill, The Second World War, I: The Gathering Storm, Cassell & Co, London, 1948, p. 592.

[34] Mountings, not guns; see Part 2 for discussion and sources.

[35] Winston Churchill, The Second World War, I: The Gathering Storm, Cassell & Co, London, 1948, p. 555.

[36] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 338.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid, p. 329.

[39] Ibid, p. 338.

[40] Fry, p. 16.

[41] Alan Raven and John Roberts, British Battleships of World War Two: The Development and Technical History of the Royal Navy’s Battleships and Battlecruisers from 1911 to 1946, Arms & Armour Press, London 1976, p. 322.

[42] https://www.winstonchurchill.org/resources/reference/churchills-political-offices-1906-1955/

[43] Winston Churchill, The Second World War, III, The Grand Alliance, Cassell & Co, London 1950, p. 113.

[44] Raven and Roberts, p. 322.

[45] Winston Churchill, The Second World War, III, The Grand Alliance, p. 781.

[46] Ibid.

[47] For conclusion to this debate and sources, see Part 2.

[48] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 335.

[49] Ibid, p. 336.

[50] Garzke and Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, p. 224.

[51] See, e.g. ibid, pp. 365-366.

[52] D. K. Brown Rebuilding the Royal Navy:Warship design since 1945, Seaforth, Barnsley, 2012, p. 19.

[53] G. C. Peden, Arms, Economics and British Strategy: from dreadnoughts to hydrogen bombs, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007, p. 241.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 367. Brown, p. 19, states 1948.

Recent Comments