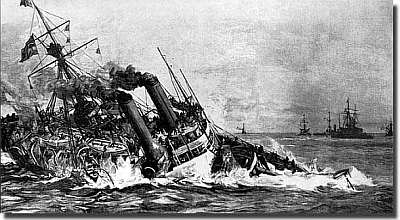

The loss of the battleship HMS Victoria to a ramming accident in June 1893 sent shock waves across the British Empire. As we saw in the last article, she went down remarkably quickly after a collision with the battleship HMS Camperdown. There was very heavy loss of life, a human tragedy that struck shock waves across Empire. In New Zealand, Parliament stood in memory of the Mediterranean Fleet’s Commander in Chief, Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon, drowned with his flagship. He had been Commander in Chief of the Australasian Squadron not long before.

The appalling human loss was the first priority for stunned officials and public alike; and the Empire mourned. However, thought soon turned to the fiscal implication. Britain had spent many millions of pounds building a battle-fleet, all to the highest engineering specifications of the day. And yet the very latest battleship – a citadel ship that was meant to be able to shake off damage at either end – had gone down less than a quarter of an hour after being rammed near her bows. Were the rest also as vulnerable?

The issue was political as much as technical, a point made clear in Britain’s House of Parliament within minutes of the disaster being announced. Former naval architect Edward Reed – now Member for Cardiff – asked for a ‘drawing of this ship’ to be ‘placed in the Library or the Tea Room’ so that ‘those that who have some acquaintance with the construction of ships may be able to form a judgment as to how it has happened that a single blow from another vessel has sent so costly a ship and so many valuable lives to the bottom?’

The Prime Minister, William Gladstone, responded that there would be a full investigation.[1] Everybody had an opinion anyway. Some blamed Tryon. ‘His brain must have failed him,’ Reginald Bacon declared.[2] Others – such as John Fisher – crucified Tryon’s second-in-command, Rear-Admiral Alfred Hastings Markham.[3] Irrespective of who was at fault, the tragedy was also a huge embarrassment for Britain, casting a shade over the design, engineering and damage-control systems of the day. Wild rumours circulated; the Los Angeles Herald even reported that Victoria had been ‘cut in two at the aft barbette’.[4] This was ridiculous. On the other side of the world, more sensibly, New Zealand’s Parliament – still thinking about the loss of life – passed a resolution of condolence.[5] Meanwhile the editor of the Fielding Star – a newspaper serving a town and rural district in New Zealand’s North Island – suggested that there had been a ‘certain amount of neglect’, given that the watertight doors had not been closed in time. More crucially, to the editor the disaster suggested that battleships were, indeed, obsolete:

This loss should go far to prove that these huge iron monsters are unfit for ocean warfare if they are so easily destroyed. The case of the Victoria is not an isolated one. Since the loss of the Captain, over 20 years ago, England has lost more warships, by accident or misadventure, than she ever lost in the same number of years in the old naval wars…[6]

This was the point: the underlying issue was the potential vulnerability of Britain’s battleships – this at a time when the argument over their obsolescence in the face of the torpedo was at its height.

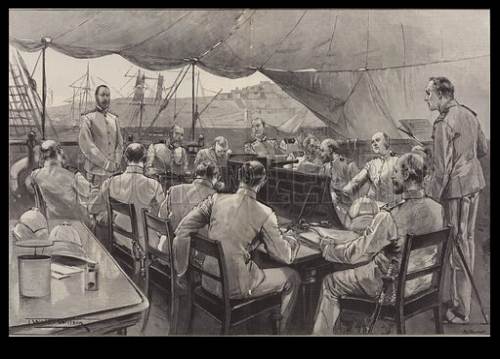

The formal enquiry took the form of a courtmartial. There were two key questions: first, how had the disaster occurred in the first place? Both ships had been manoeuvering according to a direct order from the Commander in Chief – one that, inevitably, was going to bring them into collision. What was Tryon thinking? Speculation was rife. The turning radius of each ship was well known. Had Tryon supposed the columns were further apart? Or did he envisage them wheeling past each other? All the court could conclude was that the collision was Tryon’s fault, and he had perhaps mistaken tactical radius (the distance a ship needs to turn 90 degrees) for tactical diameter (the distance to turn 180 degrees).

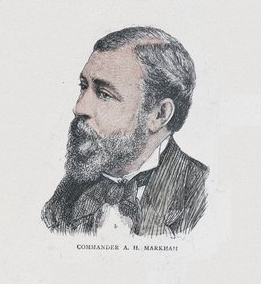

The potentially culpable officers aside from Tryon were Markham, commanding the second column of battleships from HMS Camperdown, and Victoria‘s captain, Maurice Bourke. Markham was a competent naval officer, but his enthusiasms were towards the sciences: he was, in many respects, a classic ‘gentleman scientist’ of the period. His family had emigrated to the United States, settling in Wisconsin; but he remained with the Royal Navy and was involved with the British Arctic Expedition of 1875-76. He was also an enthusiastic bird-watcher who had discovered two new species and, wearing another hat, the designer of New Zealand’s national flag in 1869.

Bourke was a career officer and competent commander. However, he had been courtmartialled for grounding Victoria in 1892; and although he kept his command, was already under a cloud. Now the ship was lost – and as captain, the default liability rested with him. He was acutely aware of the point as the ship went down. Rescuers on HMS Nile found him a broken man: ‘He did not know how to stand nor which way to look and always had his hand over his face on deck. Down below he sat all day long with his face buried in his arms and I don’t believe he ate anything at all.’[7]

In the end both men were absolved. Neither the court, nor the Board of Admiralty, were prepared to set a precedent by which an officer was convicted for obeying a senior’s command. But the disaster had its effect on Bourke, and he died just seven years later while serving as Secretary to the First Sea Lord. Markham’s subsequent career, too, stood in the shade of the disaster. He knew it, too: he asked for a further court-martial to clear his name. This was refused. He ended up on half-pay, was promoted Vice-Admiral in 1897, then was made Commander in Chief of the Nore in 1901.

From the historical perspective it seems clear the Victoria tragedy was systemic. The Royal Navy had been pre-eminent since Trafalgar – and procedures were locked in the structured formula of blind obedience that had guided the service in prior centuries. Nelson had also questioned that tradition, but his efforts essentially died with him, irrespective of the victory that his initiative and risk-taking had bought. Meanwhile, technology moved on. Late industrial-age naval technologies and the expected tactics of the 1880s and 1890s were different from what Nelson had faced, which to Tryon demanded new approaches to command. From this emerged his TA system, in which individual officers were expected to ‘follow the leader’ when the flagship hoisted the T and A flags. But he also meant that they had leeway to show initiative – a point harking back to Nelson.

The problem was that such an idea could not be properly implemented in a late nineteenth century service where heirarchical command culture was embedded. The bearing this has on the Victoria disaster is moot: Tryon explicitly signalled Markham to commit to the manoeuver, after Markham delayed executing it because it presented as nonsensical. Still, the Victoria disaster generally highlighted the gulf between Tryon’s expectations of his commanders and the reality of the tradition he was trying to modify. It was another ten years and a new century before the Royal Navy underwent some – though not all – of the cultural reforms that were needed. Even then, old habits died hard. Issues of insufficient initiative continued to dog the Royal Navy into the First World War.

The second issue facing the enquiry was the fact that a new battleship had been sunk after a collision that holed her forwards. This should not have happened; Victoria – as a citadel ship – had been designed to survive such damage. The issue was serious. Many of Britain’s battleships at the time had been designed around the same principle. Later, William White, the Director of Naval Construction, summarised the primary issues associated with the engineering, as they emerged in the courtmartial.[8]

Investigation extended to using water-tank models and revealed a number of issues. Perhaps the key point was that the force of impact had distorted the hull, damaging watertight bulkheads and apparently forcing open doors that had been closed. Other doors took more time to close than was available.[9] Another key problem was that the ship had not been closed up generally; they were coming to anchor on a hot day when the men were desperate for ventilation. Once the water reached the main deck it began to pour through open scuttles, doors and gun-ports. All this compromised the citadel. Analysis showed that water had even flowed from coal bunkers above the armoured deck into bunkers below it. The enquiry concluded that, had the ship been secured for battle, she would likely not have sunk from the damage inflicted on her by the ramming.[10]

This was small comfort to those who had lost loved ones in the disaster, but it did reassure the Admiralty of the early 1890s that their expensive battleship force was not made of eggshells and liable to sink at the first blow.

For more on Britain’s battleships, check out my book Britain’s Last Battleships.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2019

[1] Hansard 1803-2005, 23 June 1893, https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1893/jun/23/the-loss-of-hms-victoria, accessed 28 August 2019.

[2] Quoted in Richard Hough, Admirals In Collision, reprint by Periscope Publishing, Penzance, 2003, p.6.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Los Angeles Herald, 25 June 1893.

[5] New Zealand Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 79, Fourth Session of the Eleventh Parliament, 27 June 1893.

[6] Fielding Star, 27 June 1893.

[7] Quoted in http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/Maurice_Archibald_Bourke

[8] William H. White, ‘Report by the Assistant Controller and Director of Naval Construction, Based Upon Minutes of Proceedings of the Court Martial Appointed to Inquire into the Loss of Her Majesty’s Ship “Victoria”’, 15 September 1893, at http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/Report_on_the_Loss_of_H.M.S._Victoria, accessed 28 August 2019.

[9] William H. White, ‘Report by the Assistant Controller and Director of Naval Construction, Based Upon Minutes of Proceedings of the Court Martial Appointed to Inquire into the Loss of Her Majesty’s Ship “Victoria”’, 15 September 1893, at http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/Report_on_the_Loss_of_H.M.S._Victoria, accessed 28 August 2019.

[10] Norman Friedman, British Battleships of the Victorian Era, Seaforth, Barnsley, 2018, p. 204.

ich hatte Recht 🙂 mituns