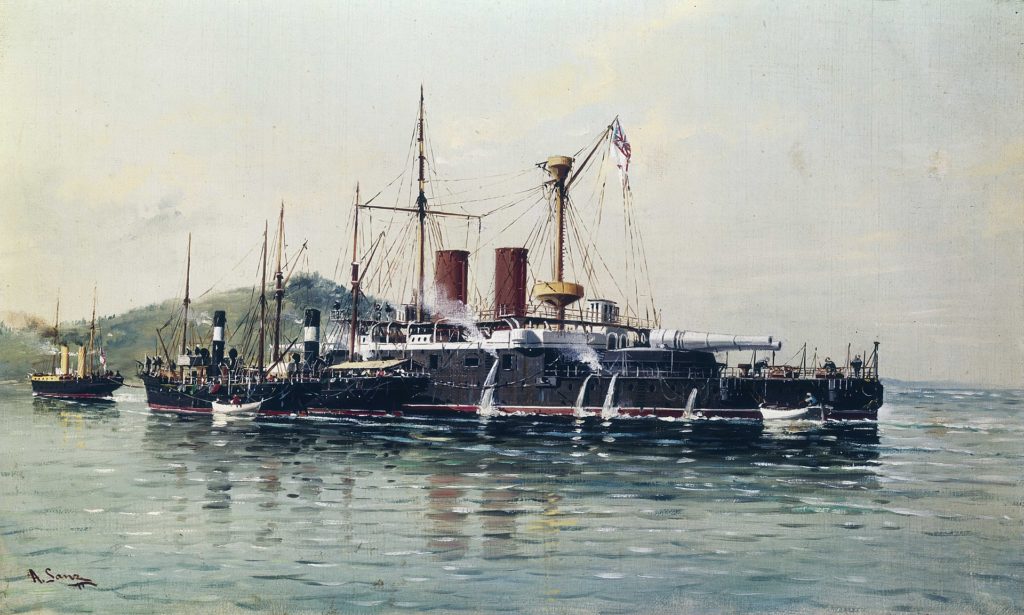

In an earlier article we explored the story of HMS Collingwood, a British battleship that the Royal Navy’s Director of Naval Construction, Nathaniel Barbaby, sketched in 1880 and which was detailed by his assistant, William White.[1] Collingwood was soon followed by five similar ships. These warships, the Admirals, are often considered Britain’s first class of battleships after decades of building one-offs and pairs.[2]

This point is not merely because the term itself – ‘battleship’ – was officially adopted by the Royal Navy in 1887 and retroactively applied. The issue is whether the ‘Admirals’ were a true ‘class’ in the sense of later classes? The fact that many reference works usually list four of the six ‘Admirals’ as a class[3] does not reduce the fact that they were never planned as such – and the design of each was subject to extensive debate. If we look more closely, we find that one of the reasons why they are often called a ‘class’ today flows from the way they were treated by the first naval historians to look at this period, writing in the early-mid twentieth century. To these historians, the ‘Admirals’ – which contained many of the characteristics of subsequent battleships – helped end the Royal Navy’s so-called ‘dark ages’.[4]

However, history is never static: the way we understand the data often changes as new questions are posed or new information is uncovered. As we saw in the previous article, while this notion of a ‘dark age’ preceding the ‘Admirals’ emerged among historians such as Oscar Parkes during the mid-twentieth century, that has been shown by later historians to be a view of hindsight, and something of a myth.[5]

The point is made clear if we explore the rather convoluted origins of each ship in the class. In 1880, Collingwood was seen as just another one-off build, and what the Royal Navy needed next was up for debate. The Board began discussing that late in the year, a few months after Collingwood had been laid down at Pembroke. Money was tight, and the First Lord, Thomas Brassey, thought construction should focus on belted cruisers. The Board wanted a counter to the Italian battleship Lepanto, which carried four 17-inch guns in echelon-mounted barbettes, had no side armour, and a speed of 18 knots.[6]

In April 1881 Barnaby came up with four options, including an echelon turret ship – a gun arrangement where the main armament was amidships and the turrets offset to port and starboard. He also produced a sketch for a barbette ship in ‘lozenge’ arrangement – one heavy gun mount forward, one aft and two on the midships beams. The possibility of a repeat Collingwood did not enter the picture, although in July, Brassey proposed an improved version.[7] Other options with turrets were also considered. Debate was further fuelled by Edward Reed – former Constructor, Barnaby’s brother-in-law, and now professional rival[8] – criticising Collingwood’s armour scheme.

What to build as the next heavy ship was clearly still a matter for debate. A key issue flowed around the problem of barbettes versus turrets. Collingwood was a barbette ship, meaning her heavy guns were set in the open on a revolving platform, atop a short and fixed armoured cylinder. This was a much lighter arrangement than the turrets of the day, which were essentially massive pill-boxes requiring comparatively heavy equipment to turn them. However, the barbette system left gun crews at least partially exposed to enemy fire; and in absence of any combat experience, the theoretical arguments for and against seemed balanced.

Another issue was the pressure to increase the weight of main armament, following the Italian lead. This was finally settled in August 1881, when the Board agreed to build two modified Collingwoods, this time armed with Mk I 13.5-inch/30 calibre guns.[9] As it happened only one – Rodney – was authorised under the 1881-82 programme. The other, Howe, was deferred. Rodney was of identical dimensions to Collingwood, but displaced just over 10,300 tons.[10] The added weight increased the draft to 26’3” forward, 27’3” aft. Barnaby thought that could be restored in peacetime by reducing the ammunition.[11]

Even then, Barnaby tinkered with other designs for the 1882-83 programme, and there were calls for more heavily armed variants of the ‘Admirals’, including one with eight 8-inch guns supplementing the 13.5-inch, or another with 9.2-inch guns instead of some of the 6-inch.[12] Other voices chipped in with more radical ideas. The gun-maker and entrepreneur Sir William Armstrong believed guns had bested armour altogether, and it was better to put scarce naval money into cheaper ships with no armour and the heaviest guns. Such thinking amplified Italian practise, pushed by their naval architect Bendetto Brin, and typified by his radical Lepanto. This conceptual prelude to the Fisherian concept of the battlecruiser was debated by the Royal Institution of Naval Architects in March 1882.[13]

The problem was that there was no practical experience of how the latest technology would fare in combat. But answers had to be found to obtain political buy-in. And so debate continued, fuelled by reason, science and logic, but uninformed by experience, and given a wild-card dynamic by the speed with which technology kept changing the ground rules.[14] In part this debate was facilitated by the fact that naval budgets were constrained, allowing only one or two heavy ships a year. That made it possible for the Admiralty to keep experimenting. Into that flowed a tight budgetary position, which put pressure on decision-makers at a time when no certain direction was clear – encouraging variations. Matters were not helped by the fact that there was no naval staff; individual opinions on the Board could carry significant weight, however eccentric the idea happened to be.

For all that, funding still worked to a specific timetable. In the end the Board agreed to authorise two further ‘Admirals’ for 1882-83, making three heavy ships that year – the deferred Howe, now joined by Benbow and Camperdown. The two new ships, however, offered further variations. In an effort to restore buoyancy, Benbow and Camperdown were 330 feet long,[15] not 325 like Rodney, Howe and Collingwood.[16] Even then, their armament was left open for later decision. In the end Benbow was given the new Elswick Mk I 16.25-inch/30 calibre gun.[17] Weight was available for only two, one forward and one aft, and she was usually considered a sub-class on her own.[18] The three ships that year, in short, were all different in various ways. Nor was the Benbow experiment repeated; the battleship ordered under the 1883-84 programme, Anson, was essentially a repeat Camperdown.[19]

The way a six-strong ‘class’ emerged, then, was by one-off decisions swathed in debate. And despite riffing off a theme, they came out as variants that mixed-and-matched two hull sizes and three types of main armament. Camperdown had a 325-foot hull and 12-inch guns. Rodney and Howe had the same hull but 13.5-inch guns. Camperdown and Anson had a 330-foot hull and 13.5-inch guns, and Benbow had the same hull with 16.25-inch guns and additional 6-inch.[20] Despite a common theme, this pattern of two discrete one-offs and two pairs was little different from what had gone before. When we include the nature of the debate surrounding them, it is arguable that the ‘Admirals’ were closer to the fleet of ‘samples’ than a class of sister ships intentionally authorised to one design. Thinking was stabilising, but the jury was still out. The point is given weight by the fact that the ‘Admirals’ successors, the Victoria and Sans Pariel, were different again.[21]

All the ‘Admirals’ took years to build. Collingwood, laid down in July 1880, was not commissioned until July 1887.[22] There were major delays completing their armament, and neither Howe nor Camperdown were ready for sea until August 1889.[23] By this time they had been formally classified as ‘first class battleships’. And yet, like so many of their predecessors, the six were already obsolescent; by late 1889, William White’s Royal Sovereigns were already in development.[24]

The ‘Admirals’ primarily served with the Mediterranean Fleet. Later they were used as guard-ships. They also suffered some major incidents during their active careers. Howe ran aground on Ferrol Rock in November 1892,[25] suffering damage that would likely have sunk her had she been in deep water.[26] She was eventually re-floated, but for a while there was doubt as to whether she was worth repairing. Some months later, Camperdown rammed and sank Victoria off Tripoli, nearly also sinking in the process. Rodney and Camperdown variously served in the International Squadron formed to intervene off Crete in 1897. On 26 March that year, Camperdown fired her guns in anger at Cretan insurgents, including four 13.5-inch rounds.[27]

All the ‘Admirals’ were scrapped in the early years of the twentieth century,[28] ending the story of some of Britain’s first battleships. For details of some of Britain’s last, check out my short book Britain’s Last Battleships.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2019

[1] Norman Friedman, British Battleships of the Victorian Era, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2018 , p. 183.

[2] Summarised in ibid, pp. 375-380.

[3] See, e.g. Roger Chesneau and Eugene M. Kolesnik (eds), Conway’s All The World’s Fighting Ships 1860-1905, Conway Maritime Press, London 1979, p. 29; also Gibbons pp. 114-15.

[4] For discussion see John Francis Beeler, British Naval Policy in the Gladstone-Disraeli Era, 1866-1880, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1997, pp. 191, 202-205, 208-209.

[5] For the historiography see Steven Gray, ‘Black Diamonds: Coal, the Royal Navy and British Imperial Coaling Stations circa 1870-1914, PhD Thesis, University of Warwick, March 2014, pp. 33-35.

[6] Details in Gibbons pp. 106-107.

[7] Friedman pp. 190-191.

[8] For biography see https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Edward_James_Reed, accessed 5 August 2019.

[9] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_135-30_mk1.php, accessed 28 July 2019.

[10] Chesneau and Kolesnik (eds), p. 29; Tony Gibbons, The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers, Lansdowne Press, London 1983, p. 114.

[11] Friedman, p. 194.

[12] Friedman, p. 194.

[13] J. D’A Samuda, ‘Armoured ships and modern guns’, Transactions of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects, Vol. 23, London 1882, pp. 1-12.

[14] Of the style recounted in Friedman, pp. 195-196.

[15] Chesneau and Kolesnik (eds), p. 29.

[16] Friedman, p. 194.

[17] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_162-30_mk1.php, accessed 28 July 2019.

[18] See, e.g. Chesneau and Kolesnik (eds), p. 29.

[19] Friedman, p. 194.

[20] Per figures in Friedman, p. 381; Gibbons pp. 110-11, 114-15; and Chesneau and Kolesnik (eds), pp. 29-30.

[21] Chesneau and Kolesnik (eds), pp. 30-31.

[22] Friedman, p. 395.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Burt, p. 73.

[25] Chesneau and Kolesnik, p. 29.

[26] Ernest W. Toy ‘They all got off except the ship: Captain Hastings and the Howe’, Mariner’s Mirror, Vol. 87, No. 2, pp. 180-195.

[27] https://britishinterventionincrete.wordpress.com/category/cretan-rebels/page/2/

[28] Friedman, p. 385.