During my years at school, (sadly now too many years ago to be comforting), I

discovered the fascination of a naval world before the onset of submersibles and air

machines complicated it. Those brief months of 1914, when the war at sea had a set

of rules the ‘gentleman’ officers stood to.

I also discovered that Germany briefly held a Pacific empire, and of a ‘concession’, or

colony, on the Chinese mainland, Tsingtao. With those revelations, I first heard of a

legendary admiral and his awe-inspiring squadron of ships consisting of the armoured cruisers

Scharnhorst and Gneisenau as well as the light cruisers Leipzig, Nürnberg, Dresden, and Emden.

Each one is well known to us naval ‘geeks’. There were others, destroyers, Chinese gun

boats, survey ships, yachts … But the cruisers were the legend. This small ‘fleet’

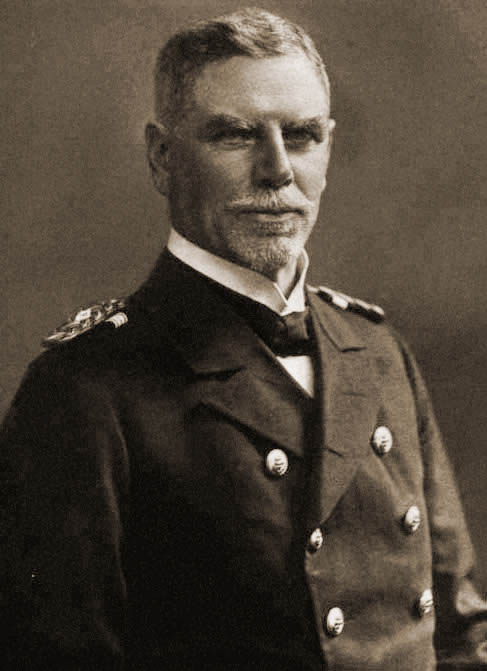

was commanded by one man at the onset of war. Vizeadmiral Maximilian von Spee.

I will confess here for the sake of clarity, I am a fan of both the man, his ‘fleet’ and

its achievements. I think he got 99% of his campaign right. It was that 1% that

brought about his eventual downfall in those cold waters off the Falkland Islands.

But as I discovered the path that was to lead him via the Chilean coast to the

Falklands, a question grew in my mind. As I read of the weeks leading up to his

victory off the Chilean port of Coronel, of his success there, and subsequently his

crushing defeat in the South Atlantic, that question grew. As I read those accounts,

the question crystallised in my mind. Why?’

Why would an admiral in his position (geographically and strategically) risk so

much on a hit and run of the Falkland Islands’ capital? What could he realistically

hope to achieve by such a risky action for his squadron, as it lay midway in its

marathon from China to the safety of home waters in Germany? I never understood

the reasoning behind the planned attack on the Falklands’ capital, Port Stanley.

The path to the Falklands’ decision commenced with the outbreak of war in August 1914, as the European situation deteriorated in July, two-thirds of von Spee’s squadron lay quietly at the then German colony of Ponape in the Carolines. He knew that should Germany become embroiled in a Franco-Russian war, return to

his Chinese home port of Tsingtao and dominance of Chinese waters by his squadron

was achievable.

Even if Britain were to take up arms, the squadron’s home waters could remain

tenable, for a time. Only the Battle-cruiser Australia posed a significant threat and

she was in distant Australasian waters. But should Japan decide to join the

fight, he would have no choice but to abandon the squadron’s home port, Tsingtao

and steam to distant waters and maybe ultimately, try to reach Germany.

Tsingtao lay on the Chinese mainland and had been seized by German machinations

in 1897. In the succeeding 17 years, the ‘colonists’ had created the facilities that to a

degree rivalled Britain’s Hong Kong? The 99-year ‘concession’ (let’s call it what it was, a colony) had grown into a symbol

of Germanic colonial ambition, of Teutonic strength on the world stage and the start

of a dream for a world empire.

In 1912, Von Spee took up naval command of Germany’s Pacific empire. After fifteen

years, Tsingtao had become a gem in the Kaiser’s crown. The East Asiatic Squadron

was probably the best posting a member of the German Navy could wish for. It was

a superb port and a favourite holiday site for the elite and the ship’s crews. People

from all the other western colonies would travel to Tsingtao for their holidays.

The parties were famous and the weather was stunning. There was even a grand race

course for the elite, where they could look down on the not-so-elite so elite stood in the

stalls! Amongst the Europeans in China, Tsingtao was the place to enjoy oneself.

In addition to sampling the offerings of Tsingtao, the Squadron visited Japan,

Singapore, Indian and Pacific waters. The colonies were a piece of paradise, a

world away from the fleet’s main base, Wilhelmshaven on Germany’s North Sea

coast.

By July 1914, Tsingtao had grown beyond the small Chinese village it had once

been and was the pride of the burgeoning Germanic empire. The Vizeadmiral must

surely have been proud of his standing within the colony, of his squadron’s

reputation & their skills.

With the outbreak of hostilities by Britain and her ally Japan, von Spee knew he

now must abandon any hope of returning to the colony. He could now only head

east to Cape Horn. All other waters only offered the prospect of a certain defeat.

Maybe not tomorrow, maybe not in the immediate weeks, but by the conclusion of

1914. Cape Horn offered him the hope of the vast remoteness of Atlantic waters and, just

maybe, ultimately a route home to Germany?

Von Spee agreed to Emden’s captain, von Müllers, plan to detach the lone cruiser into

the Indian Ocean. The admiral could then turn the remainder of his squadron

eastwards to those distant South American waters. His progress across the 8,599

Miles of waters from Ponape to Coronel was to be a flawless stratagem and his

ships’ disappearance into the empty Pacific infuriated the frustrated Entente, or allied

navies.

His arrival off the Chilean coast was to inflict the unimaginable on the mighty Royal

Navy, Its first defeat in 102 years. Not since the Battle of Lake Champlain in the War

of 1812, had the Royal Navy known defeat.

The Battle of Coronel was for his Pacific odyssey, the crowning achievement. But as

with all things military, there was a cost. We know from sources that at the battle’s

conclusion, both Scharnhorst and Gneisenau’s magazines were depleted by 60%,

which (given each gun had started with a supply of 85 shells), equated to 35 shells

remaining per gun. Offering less than ten minutes of rapid firing. (At the end of her

hard-fought Falkland battle, just before she finally succumbed, Gneisenau’s crew

were reduced to firing training shells, or blanks, at her tormentors). He also knew

the Royal Navy would be seeking revenge for the humiliating loss he’d inflicted on

them.

Given his precarious situation, why would he even consider announcing his ships

entry into the Atlantic, to attack the Falklands? Why not take the more sensible and

strategic option and slip past the islands unobserved and vanish once more, this

time into the Atlantic’s waters?

Hunger for coal is the most spoken of reason. But the light cruiser Karlsrühe had

during her brief commerce campaign in the Atlantic amassed mountains of coal

through its captures of colliers, including:

- Cornish city 5,500 tons

- Farn 6,000 tons

- Glanton 3,300 tons

- Indrani 6,700 tons

- Rio Iguassu 4,800 tons

- Strathroy 6,600 tons.

While some of that coal had been used by the lone cruiser, or rested in wrecks on

the seabed, a huge amount was potentially still available for the squadron.

Karlsrühe had been (before her cataclysmic self-destruction) in contact with Berlin by

wireless through the embassy in Rio De Janeiro. Similarly, von Spee was in contact

with Berlin through the port of Coronel. Did he know Karlsrühe captain Fritz Lüdecke

had more coal than his tiny cruiser could use waiting for him in the central Atlantic?

Whilst anchored in the Chilean Gulf of Penas, the Squadron had access to 17,000 tons

in a collier. In addition, a speculative 25,000 tons of coal awaited its shipping out to

sea from Brazil’s port of Pernambuco. An additional 15,000 tons was being organised

by Germany’s New York agents. To add to this, 30,000 tons of coal was the

Karlshure’s treasure trove.

This offered von Spee a theoretical Himalayan mountain of 89,900 tons of coal. Each

time his ships replenished their bunkers (the two armoured cruisers could carry

2,000 tons in an emergency), 3,250 tons of black gold was required. The 30,000

tons of Brazilian & American coal would permit nine complete re-coals and a

theoretical 32,500-mile range for the most coal-hungry ship in the squadron,

Dresden.

Ships

Scharnhorst

Gneisenau

Dresden

Liepzig

Nurnberg

Total

Coal Capacity

800 t *Standard Capacity*

800 t *Standard Capacity*

860 t

400 t

390 t

3,250 t

Maximum Range

4,800nmi @15kts

4,800nmi @15kts

3,600nmi @ 14 knots

4,130nmi @ 12 knots

4,130nmi @ 12 knots

Then there is the question of what von Spee expected to achieve during his ‘hit &

run’. The island’s capital had a population of 2,000 in 1914, plus the FIDF (Falklands

Island Defence Force) estimated to be 8 Officers & 267 Other Ranks. They formed

units of Coastal Artillery, foot and Mounted Infantry.

Given the war’s patriotic fervour at the time (islanders would go on to enlist to fight

in France), the FIDF would make a fight of it and boasted coastal guns. We know that on

the 12th of November, there was a sighting of an unexpected warship heading for Stanley, alarm

bells were rung in both the Cathedral and Dockyard, and the Volunteers were

mustered. On this occasion, it was the pre-dreadnought HMS Canopus, fleeing the

Coronel debacle.

On his squadron’s approach to the islands on the morning of the 8th December, both

Gneisenau & Nürnberg were sent ahead to silence the wireless station with their

guns. As they drew closer, smoke was detected within the port, and the Germans

assumed the British were burning the coal stocks to render them of no use to the

enemy. It was, in fact, two battlecruisers raising steam. But my point is, even with the

‘evidence’, he would not secure the coal, he still pressed on with the attack. Only the

beached Canopus 12-inch shell splashes finally dissuaded him. So coal was not the

burning reason (pun intended) for the raid?

If he had undertaken the assault, I doubt the squadron had sufficient armed landing

parties to dissuade 2,000 annoyed islanders and 275 FIDF troops. It’s not a brawl

he’d want to get into.

I believe his plan was a hit-and-run demonstration of German power and little else.

With the voyage north ahead of him, the last thing von Spee required was a random

hit, rendering one of his vessels into a lame duck. As would happen in the same

theatre in 1940 with the ’pocket battle ship’ Admiral Graf von Spee. Plus, there was

the expenditure of his irreplaceable ammunition.

We also know that while his squadron briefly paused in the waters of Picton Island in

Cape Horn, his captains tried to dissuade him from his plan to attack the Falklands.

Why advertise his presence or entry into Atlantic waters? Nearly all his captains

argued against the Falkland plan. Only Von Schönberg of Nürnberg and Von Spee’s

chief of staff supported the admiral. But something made the Admiral ignore sage

advice.

I think (and this is a personal theory) the answer lies in the events of the 7th

November 1914.

After 2 months, 1 week, and 4 days, the garrison of Tsingtao had finally expended their

big gun ammunition and laid down their arms. The besieging Anglo-Japanese forces

took possession of the prized colony. For an admiral who had spent two years with

his life centred on the port, who had made friends and had watched Germany’s

premier colony grow, the surrender, whilst inevitable, must have been a humiliation.

Maybe expected, but still humiliating.

He had defeated and humbled the British Empire’s mighty Royal Navy off Coronel,

but had been forced to abandon his Tsingtao friends and colleagues in arms.

I believe Von Spee was an honourable man. A man of a time in history who had only

months to live. The barbarity of war would, in 1915, bring the notion of Gentlemanly

rules at sea to an end. Von Spee seems to be a man of those diminishing times and

the Gentlemanly rules of war. He was proud of his squadron and its home port.

I have no evidence, so it’s merely supposition on my part, but I feel the loss of

Tsingtao made the admiral wish to return some portion of the favour on the British

Empire. The Falklands were both a prestigious and a juicy target thousands of miles

from any other substantial colony and support. He had already crossed the Pacific

keeping his squadron invisible until Coronel. He had then obliterated the Royal

Navy’s South Atlantic squadron, and now felt a hit and run in the Falklands was

achievable. As a result, he had no fear of encountering resistance of any substance.

With 60% of his irreplaceable ammunition expended at Colonel, he would not risk

another battle. He believed he could get in, shell the port, humiliate the British again

and then vanish into the vast waters of the South Atlantic. He could even have

spared his depleted main ammunition and relied on his secondary guns to shell the

island?

I believe the hit and run on Port Stanley was a limited payback for Tsingtao. Why

else ignore his senior officer’s advice? Why else advertise his transition from Pacific

to Atlantic waters and tell the vengeful Royal Navy his squadron’s course? Von Spee

was no fool, but in this matter, he let his heart rule his strategic decisions.

But the incident that demonstrates to me that he was a remarkable man was his

last signal as his squadron was destroyed around him. He knew he’d got it wrong.

That last signal was to his close friend & fellow ornithologist, Maerker, captain of

Gneisenau and in it he admitted that he’d got it wrong and his friend was right. He

signalled Maerker, “You were right after all”. How many admirals would admit

publicly they had screwed up?

Recent Comments