In the previous article we looked at HMS Vanguard, Britain’s last battleship. She was completed too late for the Second World War.[1] But what if she had been able to join that conflict, as originally intended when she was first planned in 1939? Could we have had a Vanguard vs. Tirpitz showdown? As completed, Vanguard corrected many of the deficiencies of the King George V class. Her underwater protection was designed to resist a 1300lb TNT charge at optimal position, better than any previous British battleship.[2] Vanguard was fast by British standards; she made 31.57 knots on trial.[3] Her armament, as we saw in the last article, was adequate to the envisaged tasks.[4]

Vanguard was also an excellent sea-boat. Apparently her ‘gentle roll’ in calm waters provoked sea-sickness in some; but her performance showed itself when a storm swept over Exercise Mariner in 1953, and she maintained 26 knots with a roll of 12 degrees[5] – better than USS Iowa could manage, although the latter had higher maximum speed.[6] This was a function of the fact that Vanguard (despite her intended Pacific role) was well suited for Atlantic waters with the flared bow.[7]

Vanguard‘s sea-keeping in part reflected the British design approach, which optimised the hull form to accommodate armament and internal systems, to some extent relying on power rather than a streamlined forward section – Iowa-style – to develop higher speeds.[8] Observers aboard Vanguard described the ‘spray flying out from either bow’ of their ship during the storm as a ‘magnificent sight’.[9] Even so, the ship’s speed/horsepower calculation makes clear she had been well optimised in terms of underwater design.

Crew habitability standards were higher than previous British ships, including a ‘superb laundry’ and dining spaces.[10] Such matters are relevant, for warships are more than lists of engineering specifications; they are homes to the crews who have to fight them.

For all that, Vanguard was not perfect. Late in the war R. J. Daniel was sent to the Bath offices of the Department of Naval Construction to calculate the effects on Vanguard of torpedo hits and was dismayed to find the ‘message that we younger officers had tried to put over in 1942/43’ in regard to asymmetric flooding had not been taken up.[11] As US naval architects William Garzke and R. O. Dulin observe, her propulsion plant employed modest steam conditions by comparison with US systems.[12] While post-war firing tests showed that British armour was better than US Class ‘A’ armour, to their analysis Vanguard’s overall protection was not as good as might be expected on a ship of that size.[13] She did, however, have a good anti-aircraft battery for the day.[14]

Vanguard came close to seeing combat. Had the Pacific war continued into late 1946, as the Allies expected, she would have joined the British Pacific Fleet, bolstered fleet air defence and participated in shore bombardments against Japanese coastal industries.

However, the only way Vanguard might have fought Axis battleships would have been if she was laid down in early 1940 and completed by late 1943, as proposed in mid-1939. It never happened, but the scenario implies that she would have been built to the mid-1939 design, ’15C’,[15] which proposed similar protection to King George V and had a fair immunity zone against 16-inch fire.[16] This version of Vanguard was otherwise a four-turret edition of the 1938 Lion, with the same propulsion plant, transom stern, secondary and anti-aircraft armament, aviation facilities, and style of superstructure.[17] Admiralty thinking in 1939 was that such a ship could have been ordered by early 1940, laid down in December, and been ready for sea trials by September-October 1943.[18] Service entry would follow in early 1944. Or – if significant resources were diverted to her construction – she might have been built to the slightly different 1940 design actually laid down,[19] and still completed in late 1943, as Churchill hoped.

Either way, her fortunes in war would likely not have devolved to a ship-to-ship slug-out with another specific battleship. Ships usually operated in task forces; ‘single ship duels’ were rare, and particular vessels did not seek out specific others in a kind of macho show-down. Vanguard – and any putative sister ships – would have been operating in conjunction with other modern battleships such as the King George V class or any of the new US battleship generation, along with smaller supporting forces. Over all would have stood the growing power and capability of aircraft as the emerging dominant weapon at sea.

Vanguard had adequate fire power in terms of the Pacific role the British envisaged in 1939-40.[20] Although armed with second-hand guns from the First World War, as we saw in the last article, a modified Mk I 15-inch/42 was not far below Second World War standards. It was adequate against Japanese heavy cruisers, rumoured ‘super-cruisers’,[21] and the IJN’s older capital ships.[22] We also have to factor in radar-assisted fire-control, detailed below. The Japanese – although equipped for night-fighting under visual conditions – lacked radar to the same sophistication. Their Type 22 could be used for fire control, but was not in the same league as the British systems, nor built in quantity.[23]

The calculation against Japan’s super-battleships, Yamato and larger designs such as A-150, all well over 60,000 tons standard, was different.[24] Here, neither Vanguard‘s armament nor armour was really adequate, although the particulars of the new Japanese vessels were not known to the Admiralty in 1939-40. While Japan was known to be building large battleships, and there was some talk that they might have 18-inch guns, the Admiralty presumed them to be 16-inch gunned vessels of about 43,000 tons, where Vanguard would have not been at a major disadvantage.

In European waters, potential opponents included the older Italian battleships – where Vanguard was clearly superior; their newer vessels – where Vanguard was broadly on par; and Germany’s new construction. Here, both the ’15C’ Vanguard and King George V were superior to the Scharnhorst class, similar to the Bismarck class, and – although with a fair immunity zone against 16-inch shells – likely to be less capable against the ‘H’ class battleships that formed the centrepiece of Hitler’s ‘Z’ plan.[25] However, Germany’s planned ‘O’ class battlecruisers, though very fast, were vulnerable to Vanguard’s guns, and Vanguard had a good immunity zone against the 38 cm SK C/34 weapons with which they were going to be armed.[26]

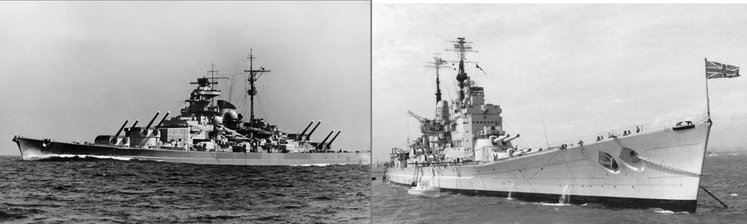

The match of interest is the Bismarck class, which had similar main armament to Vanguard, though a generation newer and with a higher rate of fire on paper.[27] The mid-1939 Vanguard design had similar armour to King George V, although there is little data on how this might have performed. During the battle of the Denmark Strait in May 1941, Prince of Wales was hit by Bismarck, but the engagement was brief and the armour system not really tested. Conversely, Vanguard’s guns were comparable (inferior in some ways, mildly superior in others) to the 14-inch weapons of the King George V class at similar ranges. As an example, while data varies with source, the Mk VII 14-inch was theoretically able to penetrate about 13 inches of side armour at 15,800 yards;[28] and the Mk I 15-inch could theoretically penetrate about 12 inches of side armour at 14,853 yards.[29] This, however, is paper specification, and the more informative data comes from practical results in action.

During the battle between Bismarck and the British Home Fleet on 27 May 1941, King George V scored up to five hits forward at about 9.12 am,[30] penetrating the armour of Bismarck’s conning tower multiple times and damaging B (‘Bruno’) main armament barbette.[31] This, coupled with two simultaneous 16-inch hits from Rodney in the same area, took out both the primary fire-control directors, the personnel on the bridge and, largely, the conning tower.[32] At 9.13 am King George V scored a hit on Bismarck’s aft fire-control director, destroying it and forcing the aft guns to local control.[33] Another series of 14-inch hits at 9.27 am, observed by HMS Norfolk, struck on or near A (‘Anton’) turret and left its guns at maximum depression. Around 10.00 am, another shell from King George V penetrated the upper citadel belt and exploded in Bismarck‘s after canteen, unfortunately killing around 100 men assembled inside.[34] While King George V’s fire was hampered by break-downs, and the specifics of hits recorded by observers at the time are debatable, the point is that these effects show what guns of this general power could do.

This gives a ‘Vanguard vs Tirpitz’ scenario, likely fought in northern waters at night or in poor visibility between Tirpitz and a British force of at least two battleships from the Home Fleet. To deploy such forces was standard tactics and not an admission by the British that their ships were weaker: Royal Navy doctrine was that, if ships were available, they should be deployed in decisive force. In such a battle the British would have had fire-control assistance from their radar. During the Battle of North Cape on 26 December 1943, radar on board HMS Duke of York – first the Type 273 surface-search system, then the Type 284P fire-control radar – enabled the British battleship to find and repeatedly hit Scharnhorst despite appalling visibility and weather.[35] Vanguard, if completed in late 1943, would have been equipped with the same system, with the Mk IX Admiralty Fire Control Table that was standard on the King George V class. As completed for real in 1946, Vanguard had the next type of main armament fire-control radar altogether, the Type 274, backed by a later-model fire-control computer, the ACFT Mk X. Conversely, although German radar was generally less advanced than the British, Tirpitz nonetheless had the most sophisticated gunnery radar fitted to a heavy German warship during the war, a Funkmess-Ortung (FuMO) 27 system.[36]

What emerges is a scenario of early 1944 in which the Admiralty receive decrypted German cypher traffic revealing that, despite the loss of Scharnhorst just a few weeks earlier, the Germans intend to sortie Tirpitz against Arctic convoy JW-56B, which departed Liverpool on 22 January and is expected at Kola on 1 February. In this scenario, Tirpitz hasn’t been damaged by X-craft in late 1943 and is fully operational. Two British battleships from the Home Fleet – the brand new Vanguard, just worked up, and a King George V class which in real life would have been HMS Duke of York, but which we shall name for this imaginary scenario after Winston Churchill’s favourite fictional naval hero, Horatio Hornblower – are despatched with supporting cruisers and destroyers to intercept.[37] In filthy weather and half-darkness they engage Tirpitz. In the engagement, Tirpitz‘ fire is effective; but Vanguard’s 15-inch shells, and the 14-inch shells of Hornblower, devastate the German battleship before she can damage the two British vessels fast enough to reduce their own fighting power.

The word ‘probably’ applies throughout. In real warfare chance plays as a part. So do people; as experience through naval history shows, a crew that has been thoroughly trained will be more effective in fighting a ship than those who are poorly trained or despondent. In engineering terms, as analysts William Garzke and Robert Dulin have pointed out, Bismarck-class armour was optimised for short range and they classified the design as ‘very vulnerable’ at longer ranges.[38] Bismarck’s final battle – pushed to point-blank – did not test the weaknesses. During the Battle of North Cape, Duke of York‘s shells defeated Scharnhorst‘s similar but heavier armour system at longer range than Bismarck was engaged. So in our hypothetical engagement it is possible Vanguard and the putative HMS Hornblower might have scored decisive hits at long range. Or maybe Tirpitz might have scored decisive hits first. Who can say?

In reality, by the time Vanguard was completed in 1946, the age of battleships was over. The only likely battleship opponents were operated by the Soviet Union – the ex-British battleship Royal Sovereign, on loan until 1949 when she was replaced in Red Navy service by the updated First World War-era Italian battleship Giulio Cesare, which sank in 1955. Neither offered a threat to Vanguard, not least because – despite having the same main armament as Vanguard, unmodified – Royal Sovereign was apparently so poorly maintained that her turrets could not rotate by the time she was returned.[39]

The only other serious gun opponents of the 1950s were the pre-war and wartime light cruisers that the Red Navy kept in service, supplemented by new-build Sverdlov class cruisers.[40] None, again, were a particular threat to Vanguard. The Soviets had plans to build up to three ‘Project 82/Stalingrad’ class battlecruisers, broadly similar to the US Alaska class; but the project died with Stalin in 1953 and these ships, in any event, were inferior to Vanguard. Again, pursuing the counter-factual, one can imagine a late-1950s Cold War-gone-hot scenario in which such ships came up against a NATO task force that included Vanguard. Such a task force could also have included one or more Iowas, making swift NATO victory certain and, of course, eliminating any chance of the Soviets actively seeking a fight. Even so, air power was a key factor at sea by this time, reducing the chance of a surface engagement.

Ultimately all these speculations offer a counterpoint to the reality of Vanguard’s truncated career, where her operational capability and life-span fell victim to changing technology and funding cuts. And what we must remember is that the ship was also home to her crew; and the capability, enthusiasm, morale and ability of that crew always makes a ship more than steel, more than just a collection of numbers and statistics.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2019

Notes

[1] http://battleshiphmsvanguard2.homestead.com/index.html, accessed 23 August 2018.

[2] Sturton (ed) p. 99, noting that design specification and real-world performance often differed.

[3] Compare speeds cited in ibid pp 50-98.

[4] The 1951 plan reflected Britain’s role protecting North Atlantic trade and military routes against Soviet interdiction.

[5] Fry, p. 19.

[6] http://battleshiphmsvanguard.homestead.com/19534.html.

[7] For discusson see http://www.worldnavalships.com/forums/archive/index.php/t-711-p-2.html

[8] Friedman The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 407, n. 20.

[9] Quoted in Fry, p. 19.

[10] http://www.worldnavalships.com/forums/archive/index.php/t-711-p-2.html

[11] R. J. Daniel, End of an Era, P. 72.

[12] Garzke and Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, p. 355.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid, pp. 354-355.

[15] For details see Ian Buxton and Ian Johnston, The Battleship Builders, pp. 49-50.

[16] Garzke and Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, p. 231.

[17] Reproduced in Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 337.

[18] Buxton and Johnston, p. 49.

[19] Norman Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, Seaforth, Barnsley, 2015, p. 329.

[20] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 336.

[21] See, e.g. http://battleshiphmsvanguard.homestead.com/Specifications.html

[22] Many were First World War vintage, see Sturton (ed) pp. 112-125.

[23] For details see, e.g. http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/T/y/Type_22_general_purpose_radar.htm, accessed 22 August 2018.

[24] For discussion of Yamato design and class see William H. Garzke and Robert O. Dulin, Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War 2, Jane’s London 1986, pp.43-126.

[25] For discussion of the ‘H’ class see, ibid, pp.311-350.

[26] For O-class armour specification see ibid, pp. 358-359.

[27] See http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNGER_15-52_skc34.php for counter-suggestion, accessed 23 August 2018.

[28] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_15-42_mk1.php, accessed 22 August 2018.

[29] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_15-42_mk1.php, accessed 22 August 2018.

[30] http://www.navweaps.com/index_tech/tech-016.php, accessed 23 August 2018.

[31] http://www.navweaps.com/index_inro/INRO_Bismarck.php, accessed 23 August 2018.

[32] Garzke and Dulin, pp. 240-241.

[33] https://www.bismarck-class.dk/bismarck/history/bisfinalbattle.html, accessed 22 August 2018.

[34] http://www.navweaps.com/index_inro/INRO_Bismarck.php, accessed 23 August 2018.

[35] Antony J. Watts, Loss of the Scharnhorst, Ian Allan, London 1972, p. 46.

[36] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNGER_Radar.php, accessed 23 August 2018.

[37] Admiral Sir Richard Howe, namesake of HMS Howe (1942), flourished only half a generation before of C. S. Forester’s fictional Admiral.

[38] http://www.navweaps.com/index_inro/INRO_Bismarck.php#XIII._Conclusions, accessed 23 August 2018.

[39] Robert M. Farley, The Battleship Book, Wildside Press, Rockville, 2015, p. 204.

[40] https://globalmaritimehistory.com/sverdlov_class_rn_response/, accessed 23 August 2018.

Recent Comments