‘WHAT-IF?’

The winter of 1918/19 was finally loosening its grip on the cold waters of the North Sea, and then after a long season, the dawn of a new spring was finally in the offering to the war weary continent. It would be the fifth year of The Great War, (the “War to End all Wars”) as it dragged on into another year. Yet after the long and bloody years of war, the battle at sea was still to be decided.

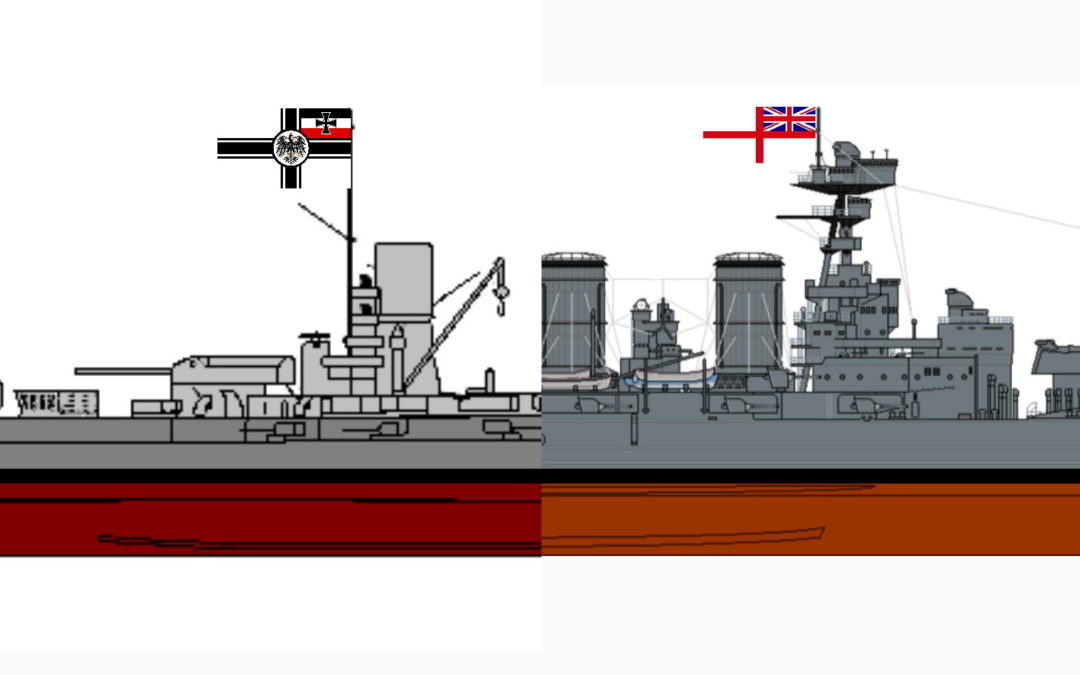

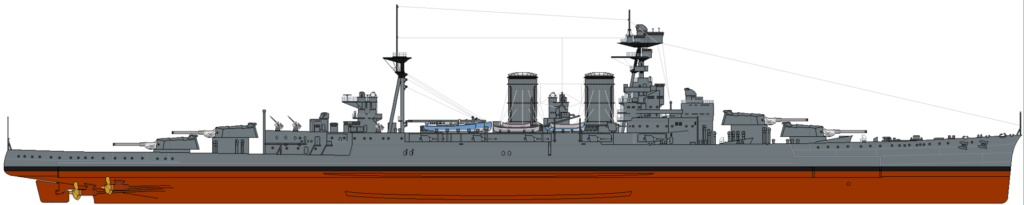

One hundred miles west off the Scandinavian coastline, on a beautifully clear day, forty British Merchant ships made slow, but steady progress as they steamed eastward towards the coast of Norway. Those heavily coal laden ships formed the latest of the Royal Navy’s monthly Scandinavian convoys and its passage had to date, been one of steady progress. It had so far been untroubled and free of any interruption by prowling German naval forces. Two miles off the starboard beam of the convoy, shielding their charges from the German naval units that lay in the port of Wilhelmshaven, ready to strike out and assail the unwary, steamed the ‘covering force’. The three capital ships were all of the Royal Navy’s latest battle-cruiser class, the Admirals, and were in one column steaming parallel to the convoy. HMS Anson led the way with her sisters, the Hood and Howe following in her wake.

High in the masts of those 46,200-ton warships, lookouts combed the horizon in systematic sweeps, searching for the first sign that the German Imperial Navy was at sea. It was from the Howe that the alarm was to be initially raised, but it spread in seconds to each of the battlecruisers, as their lookouts in turn sighted that first faint smudge of smoke that peaked over the clear skyline. Rear Admiral William Goodenough, under whose charge the convoy lay, paced the bridge on his flagship the Anson. He sensed the enemy were out as he knew of no allied forces to be in the locality. But he needed conformation that the growing smoke cloud was indeed the product of coal from the mines of the Ruhr and emanated from a German force.

Ten minutes after that initial sighting, HMS Hood was the first to confirmed to her Admiral by signal lamp that under that growing plume of smoke, steaming north towards the convoy was three of the Imperial Navy’s latest battlecruisers, Gneisenau, Scharnhorst and the Yorck.* Just as the three Admiral cruisers were fresh from the builder’s yard, so too where the Yorck battlecruisers that were rapidly drawing closer with every turn of their screws. The Hood’s report brought a further escalation in her crews’ status as the call to action stations rang out, followed throughout the covering force, as her sisterships took up the call. From the Anson flags were hoisted, and for once the merchant ships acted to a naval officers bidding with a rare promptness. Their courses were altered, and a maximum speed demanded from their overworked engines, as their admiral’s orders sent them scurrying to the north, under the charge of the escorting smaller warships.

*With only the ‘Ersatz’ named recorded, I decided to make use of those in this scenario, even though the names are of the armoured cruiser classification.

Goodenough swung his three ships onto a southerly bearing and ordered an increase of their rate of knots, to close the distance that lay between the two groups of warships. On all six capital ships, the 15-inch gunned turrets were closed up and the breaches, both German and British, were loaded with their first salvos of the day. As the distance closed with a tortuous pace of a snail, the British ships swung to the west and now steamed in a parallel course. As the British strove to keep the distance open, deep in the bowels of the three German warships, the engine room crews battled to wring their charges maximum capacity and more. They fought to close the distance, to lessen the range and allow their guns the opportunity to do as they had been conceived to do. Inflict damage on their country’s enemies.

The man on whose shoulders the lives of those 3,681 German seamen depended, Konteradmiral Viktor Harder, swung his ships 45 degrees to port, to open his field of fire, and avoid the crossing of his squadron’s ‘T’. Goodenough responded within minutes and brought his three battlecruisers further to starboard, to try and maintain the disparity in range. The huge turrets rotated slowly towards their designated targets, the twenty-four guns raising their muzzles to the horizon. On the Anson, as on all of those ships, the gunnery lieutenant commander waited for his captain’s command. The men that manned the turrets and those that served the ammunition chain that fed the huge 15-inch shells to the breaches, waited also for the word. The distance between the two forces closed almost too slowly and breath seemed to be held throughout the six metal goliaths. Finally, the captain lowered his binoculars and gave his chief gunnery officer the command he was waiting for, “you may fire when you deem the range has closed sufficiently”.

But as the German’s fought to close the distance, and the British strove to deny them the opportunity, the crews on those six battlecruisers waited for the first roar of their own big guns. It was to be the British ships that first let loose a rain of steel and explosives. The three Admirals fired the first salvo of that day from a distance of 29,000 yards and almost as one mighty ship, that first salvo from the turrets of the battlecruisers roared out. As the British 15-inch shells sped across the diminishing gap that lay between friend and foe, the German crews waited and those on the bridge offered a silent and heart felt prayer of blasphemy, “für das, was wir gleich erhalten warden”. For a little over 45 seconds twenty tons of British 15-inch shells roared through the skies between the two squadrons before twenty-four corresponding water fountains were created as the shells slammed into the water at 1,507 miles per hour, around their respective targets. All had missed, but some by a slim margin and others by too much. As the water fountains subsided, each of the British ships gunnery officers team fed the required adjustments to the turrets as the second salvo was prepared. As fresh British shells were loaded into the awaiting breeches, the German crews prayed, willing that the meterage that separated the two squadrons would diminish faster, so they too could add the roar of their own guns to the smoke and sounds that were tearing that fragment of the North Sea apart.

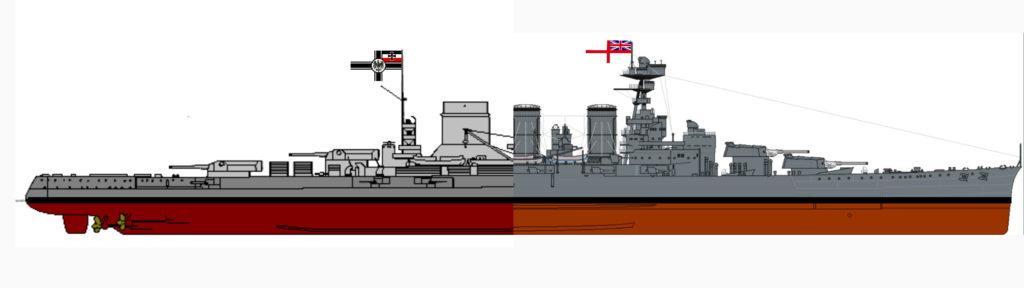

All a fictitious engagement*, but the Admiral and Yorck Battle-cruiser classes were no such fiction and were two of the great ‘what-ifs’ of the First World War. ‘What-if’ the Admirals and Yorck classes had met at sea and had fought such a battle, which class would have had the upper hand or the edge over their opponents? Which of these two final chapters in the Battle-cruiser race that had been started by the first of their kind, (HMS Invincible) had stolen the advantage? Which navy had got it ‘right’ in their newest addition to the respective fleets?

*Given (as we shall see), the disparity that existed between the two classes, in certain areas, it is unlikely that the admiral in the poorer position would place his force into such an exchange. Plus, for simplicity both groups lack screening forces and visibility is perfect, a rarity in the North Sea.

THE BEGINNING

On 2nd April 1906, the Royal Navy was to lay down the keel of what would rapidly grow to become the first in a new concept, the battlecruiser, HMS Invincible. Across the North Sea the Kaiserliche Marine (the German Imperial Navy) would respond two years later with the keel of the SMS Von der Tann. The British not wanting to lose their advantage in a race they had started, commenced work on the second generation, the Indefatigable class, and the Germans in turn with the Moltke. And so, it went on, each new class would usher in a sequel, becoming a parody of a dance, that barely faltered even as the guns began their opera of death across the fields of Europe.

But all dances must end with one last spin on the floor as the night grows old and the lights are switched off. It was ever so with the ‘Battle-cruiser Waltz’. The Royal Navy presented their new Admiral class to the world, but the demands of the war at sea had briefly changed and what was to have been four became only one, the ‘legendry’ HMS Hood. The Germans not willing to surrender the race even this late into the ‘night’, responded with the Mackensen, a class that would never reach beyond the slipways of Hamburg, Elbing and Wilhelmshaven. Other ‘concept’ designs would follow from the minds of the Kaiser’s Admirals, but the Mackensen’s were to be the final class to progress beyond the ink of the draftsmen’s pen.

The last and final class of battlecruiser to hoist the Imperial Navy’s ensign was the Derfflinger class, (Derfflinger, Lutzow and the Hindenburg). But even though no more battlecruiser were ever to be completed, further classes were planned, designed and one last group was to be laid down. Those final keels that were to have followed in the wake of the three legendry Derfflinger’s were to have been the Mackensen’s. This last creation was to comprise of an unprecedented seven hulls and of those, three would progress to the stage of being allocated a name. The lead ship was to have borne the name of a serving Field Marshall (and probably the best wearer of eccentric head gear within the Kaisers army). The second was to be the Graf Spee (named after the Admiral of the East Asiatic Squadron) and the third, the Prinz Eitel Friedrich (named after one of the Kaisers six sons).

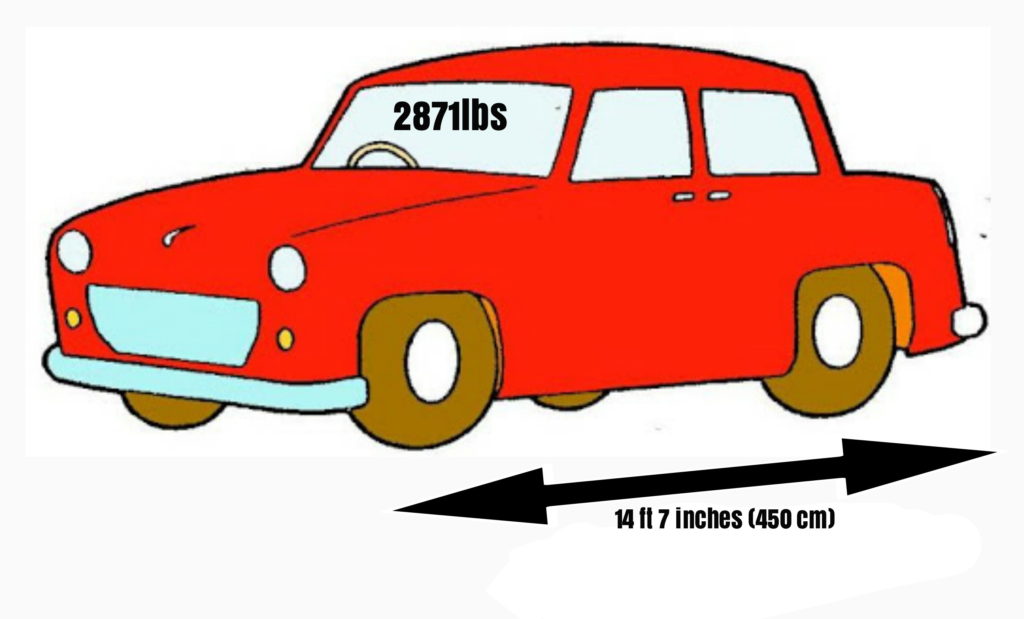

SIZE AND WEIGHT

The Mackensens were to have been 735 feet 9 inches (223 mtrs) in the length of their hulls, a 125-foot (38.1 mtrs) short fall in comparison to the Admiral’s 860 feet, (262.12 mtrs). That would equate to eight (and a half) family cars parked lengthways in a row*. The new designs width (or beam) was to be 99 feet 9 inches (30.4 mtrs), (just under seven of those kerb side parked cars). This made them 4 feet 3 inches slimmer than the Admirals 104 feet (31.7 mtrs). The planned draught was 30 feet 6 inches (9.29 mtrs) for the Germans and 31 feet 6 inches (9.6 mtrs) for the Royal Navy. The result was a British hull (and a design that was famed for its slim and rakish look) longer by a considerable amount (17%), wider by four feet (1.12 mtrs) and one foot (30.48 cm) greater in their draught. That lone ship of the Admiral class, (the Hood) would become famous throughout the world for an elongated beauty, but in their own way the Mackensens had their own elegance.

In tonnage we have two figures for the uncompleted German hulls, 30,519 tons (31,000 tonnes) standard and 34,700 tons (35,000 tonnes) under full load. The original design weight for the Admirals was 45,470 tons as standard and 46,200 tons when fully loaded. The German hull was thus lighter by 14,951 tons (31.82%) standard and 11,500 tons (24.89%) full. However, the German figures are based on a hull that was never completed, and in that journey between the draughtsman’s board and commissioning, things grow heavier. But with such a disparity, no matter what weight was added, it was probable that the shorter, slimmer and shallower Mackensens would have been of a considerably less tonnage.

* The average car length is around 4500 mm or 14,7 feet and has a weight of approximately 2871 lbs,

* The average car length is around 4500 mm or 14,7 feet and has a weight of approximately 2871 lbs,

PROPULSIVE POWER

The seven German hulls were to have had thirty-two boilers, producing in theory a total of 88,769 shaft horsepower. These would in turn provide steam power to four geared turbines, with each unit driving a shaft, which in turn spun a propeller. The projected speed for the class was to have been 28 knots, with a range of 8,000 nautical sea miles while making 14 knots.

In turn the Admirals had eight less boilers, (numbering twenty-four in total), and this smaller number was to produce 144,000 shp. Each of the German boilers were to have generated 2,774.03 shp, while the Admiral’s boilers created 6,000 shp as individual units. Those twenty-four British boilers were also to provide power to four geared steam turbines and four propellers. The net result for the Royal Navy was to be a class capable of 32 knots and with a steaming range of 7,500 miles at 14 knots. The Admirals achieved 53.76% more power per boiler and as a result moved their bigger and heavier hulls at 4 knots faster. But their steaming range was 500 miles less, at the same economic rate of travel, 14 knots.

BIG GUNS

Each of the seven German hulls were to have had thirty-two boilers, producing in theory a total of 88,769 shaft horsepower. These would in turn provide steam power to four geared turbines, with each unit driving a shaft, which in turn spun a propeller. The projected speed for the class was to have been 28 knots, with a range of 8,000 nautical sea miles while making 14 knots.

In turn the Admirals had eight less boilers, (numbering twenty-four in total), and this smaller number was to produce 144,000 shp. Each of the German boilers were to have generated 2,774.03 shp, while the Admiral’s boilers created 6,000 shp as individual units. Those twenty-four British boilers were also to provide power to four geared steam turbines and four propellers. The net result for the Royal Navy was to be a class capable of 32 knots and with a steaming range of 7,500 miles at 14 knots. The Admirals achieved 53.76% more power per boiler and as a result moved their bigger and heavier hulls at 4 knots faster. But their steaming range was 500 miles less, at the same economic rate of travel, 14 knots.

BIG GUNS

The reason for the existence of any capital ship must be that of her main armament. Everything on board was secondary to those big guns and merely served to ensure the ship could deploy to where her Admirals deemed they were to be needed and once there to be of sufficient offensive fire power to enforce their foreign countries policy. Superficially the main armament is a simple comparison, with the German hulls having eight super firing 35 cm (13.78 inch) SK L/45 guns mounted into four turrets, two fore and two aft. The Admirals were to have had four twin 15-inch (38 cm) MK II guns, with the same layout, two fore and two aft. Simple? A 15-inch gun out classes a weapon of 13.78-inch calibre, but maybe the weight of shell and its destructive power could tell a different tale? Could the Germans be at such a disadvantage?

We need to look closer at the two calibres and compare their ‘power’ in action, to see if there were any Germanic mitigating factors. The German 13.8-inch, (or 35 cm) gun was a new weapon (designed in 1914 for the Imperial Navy) and had a weight of circa 162,000 lbs (73,500 kg) which equates to about 72.32 tons (73.48 tonnes) each and 578.56 tons (587.84 tonnes) for all eight weapons. That would be equal in weight to fifty-six of those family cars. The length was 51 feet 8 3/32” (15.75 mtrs) which is three and a half of the cars. The weapon was to have achieved 2.5 rounds per minute from each of the ship’s eight barrels.

The British 15-inch weapon was designed in 1912 and rushed into service three years later, sidestepping many of the time-consuming processes a new weapon would conventionally be required to pass. It would in the next few decades go on to see service in the battleship classes of the Queen Elizabeth, Royal Sovereign and Vanguard, the battlecruiser classes Glorious, Repulse and Admiral and the monitors Marshal Soult, Erebus and Roberts classes.

With the breech mechanism included the individual 15-inch gun weighed 224,000 lbs. (101,605 kg), or seventy-eight of those cars. The rate of fire was around two rounds per minute giving the larger, heavier calibre British weapon a slower rate of fire. The Hood was in fact to achieve 32 seconds with her MKII mountings. But these figures tell only a fraction of the tale and we need to compare the shell weight and the destruction it wrought on its impact, in order to make as fair a comparison as we can, with two weapons of such differing calibres.

The German shell was a cartridge and bag combination, with both armour piercing (APC) and High explosive (HE) variants carried deep within the magazines. The APC weighed 1322 lbs (600 kg) and the HE (L/4,2 fuse) the same, (around half a car). The APC bursting charge was about 44 lbs (20 kg) and the HE an approximate 88 lbs (40 kg).

In length the APC was 43 inches (108 cm) and the HE 56 inches (144 cm), both figures being approximate. The speed the shell left the barrel, (or the muzzle velocity) was 2,674 feet per second (815 meters per second (mps) * / 1823.1 mph)), the barrel life was 250 rounds and the magazines held 90 shells per barrel.

The British shell in turn offered seven variants for the Gunnery Officer to select from, during the period of the First World War. These ranged from the Shrapnel, CPC and HE variant at 1,920 lbs. (871 kg), to the APC Mark III (4crh – Greenboy) , also of 1,910 lbs. The length of these seven shells was (between the CPC and the HE variants) 63.3 inches (160.8 cm) diminishing to the APC Mark IA at 54.5 inches (138.4 cm).

As a guide the APC 4crh had a muzzle velocity of 2,467 feet per second (752 mps/1682 mph, 2.19 Mach) and the barrel had a life of 335 firings. The magazines for the Admirals would have held 110 rounds for the ‘A’ & ‘B’ turrets, and 100 for the stern ‘Y’ & ‘X’ turrets. The Admirals were also the first RN dreadnoughts to locate their magazines beneath the shell rooms. The ‘Chatham Test’ had demonstrated that if a mine exploded beneath the magazine the flood waters would ingress fast enough to cancel any risk of a detonation. The configuration was to be used in all subsequent British Battleship designs. The layout of the two rooms had a net result of reducing the number of shells carried from the average 120 that the 15-inch gun held in other ships to the lower figure.

But the above glut of figures all illustrates the role of the gun in its ability to launch a projectile over as longer distance as it could achieve, with some semblance of accuracy. Once on target the goal was to burrow the 1.4 car weighted shell as deep as was possible and then to serve the maximum amount of damage to its adversaries’ vitals.

The smaller German weapon had, when using a 1,323 lbs. (600 kg) shell (3.3 motorbikes) with an elevation of 16 degrees, a range of circa 21,870 yards (20,000 mtrs). An increase of degrees on the 35 cm barrel, pushed the range out to about 25,480 yards (23,300 mtrs). In response the British shell could range out to 29,000 yards (26,520 mtrs), a 3,520-yard advantage. With a British 4 knot gain, this equated to 26 salvos, before the Germans (if they could close the range somehow) could reply with salvo number one.

CHANGE OF TACK

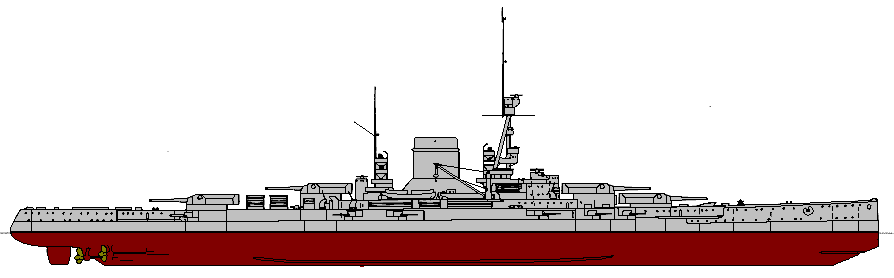

As we work our way through these figures it becomes apparent that if the two classes had ever met in the North Sea, the Admirals would have had an overwhelming advantage on the German ships. But if we at this stage could see this flaw, then so too could the German Admirals. If the Imperial Navy were to sidestep a repeat of the SMS Blucher miscalculation, and the next generation of German Battlecruisers were not to be obsolete before they were even completed, something drastic needed to be done. By 1915 the navy had already, (short of scrapping them) three Mackensen hulls committed too. But there was both the scope and the freedom to revise those projected four remaining hulls. There were already plans for the ship’s machinery and hull, limiting the freedom there, if time was to be preserved and not wasted. But the guns that were to be house in those four turrets needed to be upgraded at the very least. The decision was consequently made to divert the remaining ships into a sub-class of a new and better armed battlecruiser. These four hulls (in conjunction with the Bayern class of super-dreadnoughts) would surely offer a stronger and more viable challenge to the Admiral, Revenge and Queen Elizabeth classes that were being built in the shipyards across the North Sea? The new class was given the provisional name of Ersatz Yorck (or Replacement Yorck) and two of her sister ships the Ersatz Gneisenau, and Ersatz Scharnhorst. All three of the latter were armoured cruisers and the final two lay on the seabed of the South Atlantic, having been lost during December 1914 to the guns of two British Battlecruisers.

* Concorde flew at 2.1 mach, a slower speed than the shells 2.3 mach

SIZE AND WEIGHT

The hull design of the Ersatz Yorcks was to have been increased from the Mackensen blueprint to a planned length of 747 feet 5 inches (227.8 mtrs), a beam of 99 feet 9 inches (30.40 mtrs) and a draught of 28 feet 6 17/23 inches and under full load 30 feet 6 5/32 inches (8.7 mtrs normal, 9.3 mtrs full). The result was to have been a hull that had been lengthened by 16 feet 7 inches, (5.05 mtrs) 1.13 cars)) but the beam and draught remained unaltered from how they would have been in their previous life’s as Mackensens. [To my mind, as complicated as it would be to lengthen a pre-existing design, to increase the width or beam would have entailed a far larger amount of design work?]. The net result would still be a hull shorter than its British rivals, with the Admirals hull extending a further 112 feet 7 inches beyond the Yorck’s bow. But the new elongated German hulls would allow for the installation of a heavier calibre main gun with its longer barrels and the larger magazine storage the ships main armament would as a result demand.

The projected tonnage for the new Imperial battlecruiser was to have been 33,000 tons (33,500 tonnes) at normal displacement, rising to an envisaged 37,000 tons (38,000 tonnes) when fully equipped, subject once more to a plausible weight gain between draftsman’s board and commissioning. This was an increase of 2,490 tons (2,529.95 tonnes) over the Mackensen, rising to 2,700 tons (2,734.32 tonnes) when they were finally commissioned and ready for sea. The Admirals were however to retain their tonnage dominance, still greater by 12,470 tons (12,670.10 tonnes) under normal displacement, diminishing to 8,200 tons (8,331.58 tonnes) on full load.

PROPULSIVE POWER

At this stage the conclusions between the hull dimensions and weight remains greatly in the British favour. But as has been said above, the ability to move through the seas and to carry a heavier gun, were more important factors than the shape and size of the ship. If the smaller vessel packed the same punch, speed and protection, then she had the advantage of being a smaller and harder to hit target.

The Germans (possibly to make use of an existing design and not to incur a time penalty a total redesign would entail) decided to retain the tried and tested installation of four sets of Parsons Steam Turbines, each driving a shaft to which was fixed a 3-bladed propeller that was 13 feet 9 inches (4.2 mtrs) in their diameters. The four turbines were to be supplied with steam by twenty-four coal-fired Schulz-Thornycroft single-ended boilers, but these were now to be supplemented by eight oil-fired Schulz-Thornycroft double-ended boilers. The Yorcks were intended to mount a pair of rudders side by side for improved steerage.

The intended power plant was to have provided 90,000 shp, turning the propellers at 295 revolutions per minute, or one rotation every 0.20 of a second, the same as the preceding Mackensen class ships. But with the longer (& heavier) hull they would have been penalized with a reduction in their speed. The Mackensens goal of 28 knots was to be reduced to 27.3 knots. (32.22 to 31.41 mph* a 0.75 mph difference). With their oil and coal fuel stores topped off, the ships were estimated to have been capable of steaming 5,500 nautical miles (10,186 km) and at a cruising speed of 14 knots 6,300 miles (11,666 km). Here too the game is set and match to the Admirals with their 32 knots and 7,500-mile (13890 km) steaming range.

* The average walking speed is 3.1 mph and a slow run, 4.5 mph.

PERSONNEL

The Yorck were to have been crewed by 47 officers and 1,180 sailors, which is one officer more than the Mackensen and 40 enlisted men less. But as with the Mackensens , the Germans required a disproportionate number of men than the Admirals 820 men to crew their ships.

THE BIG GUNS

The decision was made, (to counter the Admirals heavier calibre), to increase the turreted guns from the 13.8-inch (35 mm) variant to the new 15-inch (38 cm) SKL/45 gun. These were already designed and proven, as they were at that point in the war, being supplied to the newly completed Bayern class ships and were of a proven success in trials.

The German 14.96-inch gun (38 cm) had a weight of circa 176,370 lbs (80,000 kg) or 78.73 tons per barrel, (which at the risk of becoming tedious equates to 61.43 of those cars in weight). This was 6.45 tons more than the original 13.8-inch gun, adding a total of 51 tons for the full eight guns carried. The barrel was 673 inches (17.100 mtrs) in its length and were as a result 4 feet 5 inches (1.34 mtrs) longer than the earlier 13.8-inch gun. That necessitated the addition of 8 feet 10 inches (2.67 mtrs) to the length of deck the 4-turret configuration would require to house the new 14.96 cm guns. The difference between the Mackensen and the Yorck hulls was as we have noted 16 feet 7 inches (5.05 mtrs) and in the

The German 15-inch gun (14.96 inch) had a weight of circa 176,370 lbs (80,000 kg) or 78.73 tons per barrel, (which at the risk of becoming tedious equates to 61.43 of those cars in weight). This was 6.45 tons more than the original 13.8-inch gun, adding a total of 51 tons for the full eight guns carried. The barrel was 673 inches (17.100 mtrs) in its length and were as a result 4 feet 5 inches (1.34 mtrs) longer than the earlier 13.8-inch gun. That necessitated the addition of 8 feet 10 inches (2.67 mtrs) to the length of deck the 4-turret configuration would require to house the new 15 cm guns. The difference between the Mackensen and the Yorck hulls was as we have noted 16 feet 7 inches (5.05 mtrs) and in the longer barrels, we have already found the reason for 32% of that increase in the hull. We have not factored in the turret and munitions size increases.

The projectile or shell fired from the 15-inch barrels was 52.4 inches (108 cm) in its APC format, and 61.0 inches (156 cm) in the HE version. The difference between the 35 cm and the 15-inch shells was 9.4 inches (23 cm) and 5 inches (12.7 cm) respectively. Not a large measurement in comparison to the hulls overall size, but the Ersatz Yorck were to have carried 90 rounds per gun (30 HE, 60 APC) and 720 in total, all would have forced an increase in the magazines and the machinery to process the munitions from the depth of the hull to the hungry breeches.

The APC shell weighed 1,653 lbs (750 kg) and the HE format was identical. The individual shell was 330 lbs greater than the Mackensen munitions and the 720 shells brought an additional 106.07 tons (107.77 tonnes) to the ship’s displacement. Once more in the scale of things a small figure, but in comparison to the 2490 tonnage (2,529 tonnes) between, Mackensen and Yorck, it was significant. Gun and their munitions added a total of 157 tons (159.5 tonnes) to the design, but that excludes the increase in the size of the support equipment and the turrets. The four turrets were to be mounted two aft and two forward, with the by now standard super firing configuration. The 15-inch SKL/45-gun design was housed in turrets that were originally conceived with a depression and elevation range of between −8 degrees and + 16 degrees. But possibly (as with the Bayern’s in the latter stages of the war), the elevation would have been increased to 20 degrees, a common practice for German naval weapons during the latter part of the conflict. Once the guns had fired, they needed to be lowered once more to 2.5 degrees to reload. During trials conducted on the surrendered Baden in the post-war period, (by the Royal Navy), loading tests revealed the Baden took only 23 seconds from the time the guns fired until they were ready to fire again. This compared with the 32 seconds for the 15 inches on the Hood, was a distinct advantage.

The sources available to us today (www.navweaps.com) record the German 15-inch gun, (when firing at 20 degrees elevation) as having a range of 25,370 yards (23,200 mtrs). At their maximum elevation of 30 degrees, the British 15-inch MKII gun could range out to 29,000 yards (26,520 mtrs), which leaves a distance of 3,630 yards (3,139.27 mtrs) the slower German ships would need to cross, while under fire from their quicker speedier adversaries. The Germans would need (at full speed) eighteen minutes (and thirty six seconds in a flat calm sea to cross that 3,630-yard short fall, a period during which the British would be able to deliver a staggering thirty four uncontested salvos. If shoes were reversed and the Germans had the speed superiority, they would manage forty-eight salvoes, but once the shell had crossed the void and found its target how much damage did it inflict?

The German shell was the lighter of the two at 1,653 lbs (750 kg) or half a car)) and had for the APC variant a bursting charge of about 55 lbs (25 kg) TNT and the HE variant had a charge of 147.7 lbs. (67.0 kg) TNT. The British shell was considerably heavier at 1,910 Ibs for the APC and 1,965 Ibs for the HE types (60% of that car). The bursting charge for the APC(MK XIIIa) was however only 45.3 lbs (20.5 kg) of Shellite and the HE (8crh) 220 lbs (101.6 kg) of Lyditte. The British were at a 9.7 Ib (4.3kg) disadvantage with the APC, but a greater 72.3 Ibs (32.79kg) dominance with the HE variant.

The maximum depth of armour the respective shells decreased as the range became elongated.

| YARDS | BRITISH | GERMAN |

| 1,920 lb | 1,653 lb | |

| 0 | 18”(AP) | |

| 8,229 | 16” | |

| 9,510 | 14 (AP) | |

| 10,000 | 14 (AP) | |

| 10,280 | 13.5 (AP) | |

| 10,936 | 15.35” | |

| 13,670 | 13.78” | |

| 14,853 | 12” | |

| 19,707 | 11” | |

| 21,872 | 10.43” | |

| 23,734 | 9” | |

| 25,000+ | 8.66 |

We are left with the clear evidence that the longer ranged British shell was heavier, but carried a smaller APC bursting (or explosive) charge, but it came with bigger bang in the HE version. It appears the depth of armour required to prevent the shell passing through was consistent between the two 15-inch weapons. But with its larger APC charge, once having pierced the armour the German shell would create more havoc as it exploded. But the impact of a British HE shell with its bigger charge (20.42% bigger approximately) would have wrought more damage to unarmoured areas of the ship.

The secondary armament for a battleship is purely defensive in its role, so it is redundant in this comparison. But we are left with one more factor to compare, the defensive capacity or armour scheme of the two designs. It was the strength of the armours steel plates that provided protection from the incoming shells and allowed the ship to retain her place within the battle.

PROTECTION

We need to look briefly at the two classes vulnerability to their respective 15-inch shells and how much (in theory) they were susceptible to damage being inflicted. The Admirals and the Yorcks armour schemes were on a simple level as follows:

| Sizes are in inches | ADMIRALS | YORCKS |

| Central belt | 12 (slope sides made it effective as if 13) | 11.8 |

| Belt towards Bow | 6 to 5 | 4.7 to 3.9 |

| Belt towards stern | 6 to 5 | Nil |

| Deck over citadel | 5 | 3.1 |

| Deck in other areas | 0.75 | 1.18 |

| Turrets sides | 11 to 12 | 9.6 |

| Turret face | 15 | 11.8 |

| Turret roof | 5 | 5.9 |

| Turret Rear | ? | 11.4 |

| Casements | ? | 5.9 |

| Barbettes | 12 max | ? |

| Conning tower sides | 9 to 11 | 5.1 to 11.81 |

| Torpedo bulkheads | 0.75 to 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Aft coning tower sides | ? | 7.9 |

| Aft conning tower roof | ? | 2 |

To stand any chance of piercing the thicker of the Admirals armour, the Yorcks would need to close to within an approximate 15,000-yards (13,716 mtrs). In turn the Admirals would also need to be within the 15,000-yards mark to penetrate through to the ship’s vitals. Given we do not have all the figures for distances listed and have to speculate at the missing sums overall the two 15-inch guns seem to have a similar curve in the rate their shells could crash through their opponent’s armour.

TO CONCLUDE

TO CONCLUDE

So, let us return to that 1920 morning in the North Sea. First it is necessary to highlight that this is an exercise of both theory and whimsy. The weather in our encounter is clear with maximum visibility and a glass flat sea, both a rarity in the North Sea. Plus, both Admirals have come to the encounter minus any screening force, also most unlikely to happen. With these guidelines established, let us conclude.

In size the Yorcks were the smaller and more compact of the two designs. If you want elongated beauty and stunning lines then the Admiral is where your heart will lay, as the one Admiral that hoisted the White Ensign, the Hood, grew to become the darling of the British Empire and her loss tore at the nations heart strings. But on a practical level the Germans managed to squeeze the same ordnance into a smaller (but slower) hull.

As to tonnage, we have the Hoods figures from life and the Yorcks based on the calculations of a draughtsman. If the German ships had reached commissioning, then the totals might have been higher. But they might not have, so comparing these figures, we will make use of the standard (or unladen) totals. The Yorcks were 27.42% lighter than their British rivals (and for those curious as I am that is 19% on the projected full displacement).

Within these figures are the weight of the defensive armour systems of both ships. Where we can make a comparison, (given the incomplete German records), the Admirals have the slight advantage.

Both designs used four turbines, but the Germans were to have installed thirty-two boilers to the British twenty-four, and in doing so produced 50,000 less shp in total. With their streamlined hulls the Admirals could at a full run make their designed speed of 32 knots, a speed Hood even surpassed, while the Germans design speed was for a more sedate 27.3 knots, the difference being a good running speed, and with shells landing all around your hull, every knot advantage would be less time to reach a closer range.

Finally, before we move onto the decisive matter of hitting power, the Yorcks were to have been crewed by 1,227 officers and men, while the Admirals were to be handled by 820 personnel. That is a shocking 407 men difference, which is 49.63% more than the British ships.

As a comparison the Bayern class battleships were crewed by 1171 officers and men, while the comparative Queen Elizabeth’s were manned with 1262 (peacetime). The original battlecruiser HMS Invincible had 1000 men (approximately) to the first German Battlecruiser, the von der Tann’s 923. On a general comparison the Admirals were unusually light in the crew that was required and the Yorcks around the norm. But 407 men equates to a weight increase and each additional crew member above the 820 Admiral total would bring additional needs and weight to the hull, in what they needed to be fed etc. Not a huge figure in comparison to the guns, but still an added weight. And the Mackensens? They were to have been crewed by 46 officers and 1,140 enlisted men, a total of 1,186, surpassing even the Yorcks.

Now we move on to the reason for the ships very existence. The Big Guns. The Germans had extracted themselves from the blind alley the Mackensen design was going to lead them down and increased the calibre size to match the Admirals. But shell for shell the Royal Navy’s ordinance were heavier, plus the HE bursting charge, or explosive was greater. The larger amount of TNT carried by one British shell equated to the additional explosive force of a 5.9-inch (14.98 cm) projectile!

We know the British 15-inch gun could fire its shell 3,630 yards (3,139.27 mtrs) further than the German weapon, (based on a British 30-degree elevation). Both guns went on to exceed that range by huge amount’s, but for the Germans that was as a rail mounted land version and for the British a super charged WW2 upgrade. So, for the period we are concerned with the British could fire their shells further and the held a 4.7 knot speed advantage. The Germans would need to steam that 3,630 yards before they could return fire. As to destructive power the British had the slight edge in the depth of armour they could pierce. But once the Germans were through that ’15-inch shell alley’, they brought a slightly bigger detonation to the explosion that resulted.

The Yorcks were smaller and slower than the Admirals, but the British could fire their shells further. In their defensive armour schemes, neither had an overwhelming advantage, but the British had the smallest of edges. The only other factor that comes to mind at this stage is the two navies record of ‘hits’ scored at Jutland, and the Imperial Navy proved to have the advantage there.

If I had to choose on which ship, I stood the best chance of survival it would be the British. With a greater range and superior speed, the course of the battle was theirs to dictate. The British Admiral would be able to set the range and hold his opponent off, as he slowly but remorselessly pounded them to defeat. But every battle at sea has unknown and unexpected factors. The weather would not be so clear and calm as I have stated, and chance can change things in the blink of an eye. But for all that, the Admirals had to my mind a decisive edge over the German designs.

Recent Comments