One of the common misconceptions in naval history is the idea that the so-called ‘escalator clause’ of the Second London Naval Treaty – which allowed main gun calibre to automatically revert to 16-inch if any signatory failed to ratify the treaty – also enabled agreed displacement to rise from 35,000 to 45,000 tons. Actually the treaty itself contained no provision to automatically increase displacement – as we’ll see in this article, that alteration came later, after some diplomatic gyrations.

HMS Prince of Wales arriving in Singapore, 2 December 1941. She was less than nine months in commission. (Public domain).

The journey to and beyond that escalator clause was convoluted and had a good deal to do with the way international politics were unravelling by the mid-1930s. By this time Britain, France, the United States, Italy, Japan and Germany were all working on new battleships, either in design or actually building. The first five were signatories to the London Naval Treaty of 1930; and the sixth, Germany, coat-tailed on the rules via the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of June 1935. However, only the first three nations felt they had to actually meet the limits. Cheating had been a problem since the beginning of the system, and the successive naval treaties contained clauses requiring each party to state what they were building; but this was a double-edged sword, because to then accuse a party of cheating meant they were, basically, being accused of breaking the principles of international law. This carried diplomatic implication that ran well beyond naval agreements. Any allegations therefore had to be backed with solid evidence which was unavailable. This did not, however, prevent the democracies from hedging their bets, hence the escalator clause.

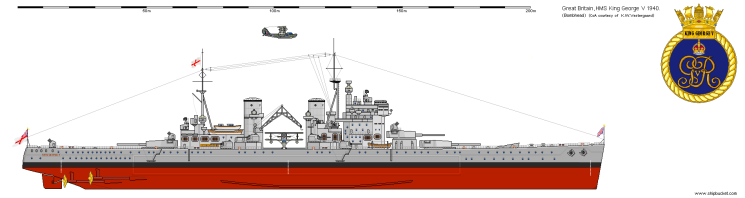

Britain’s first new battleship class were the King George V‘s, described in earlier articles. A schedule formally approved in January 1936[1] projected 10 new battleships to be laid down by 1940-41 in annual programmes on a 2-3-2-2-1 frequency.[2] This was later adjusted to add a second battleship to the 1940-41 programme.[3] However, the main problem in 1936 was that Article 4 of the second part of the Second London Naval Treaty restricted battleships to 14-inch guns on 35,000 tons standard.[4] This was signalled ahead of time,[5] and was why the two King George V class laid down under the 1936 programme, the name-ship and HMS Prince of Wales, were armed with 14-inch guns.[6]

The pressure to constrain armament came from Britain, largely for cost reasons; and did not go down well in the United States, whose naval planners were suspicious of Japan. As a result, the same clause that restricted armament to 14-inch also allowed it to revert to 16-inch if any signatories of the five-power ‘Washington Treaty’ of 1922 failed to ratify the new arrangement by 1 April 1937.[7] The Japanese were not expected to ratify, and the Admiralty hoped for 16-inch armed ships for their 1937 programme. However, that swiftly came adrift. Japanese diplomats refused to admit the point ahead of deadline,[8] but thanks to lead times, the main armament for Britain’s 1937 programme battleships had to be ordered by late 1936.[9] In absence of an early Japanese answer, this meant three repeats of the King George V.[10] Japan, as expected, refused to ratify when the time came in April 1937,[11] but by then it was too late for Britain. The US Navy, by contrast – working to a slightly different schedule and with differing constraints on their designs and industrial base – were able to up-gun their equivalent North Carolina class, as we saw in an earlier article, and then go ahead with a class of purpose-designed 16-inch gunned ships. The issue highlighted how timing was tied up in politics, fiscal schedules, industrial capacity, and even continuity of work for contractors.

HMS King George V. Drawing by Bombhead, Kim W. Vestergaard. Via Shipbucket, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This was not Britain’s only problem in 1936-37. Japanese intransigence and the worsening international situation – in which Germany was permitted to build up to 35 percent of British naval power – also suggested that the battleship programme projected in 1936 was insufficient. Expanding it was difficult. Apart from cost constraints, the practical bottleneck was the time it took to fabricate heavy guns. However, it happened that four twin Mk I 15-inch/42 calibre mountings, built in 1915-17,[12] were in storage at Devonport[13] after being removed from Courageous and Glorious during their conversion to aircraft carriers in the 1920s.[14] While the Admiralty considered the Mk I 15-inch/42 obsolescent by the late 1930s,[15] these guns were still the primary weapon of the battle fleet.[16] In April 1937 suggestions circulated in the Admiralty that the stored mountings might be used on an additional ship.[17] At the time, this did not get beyond various sketch designs projecting a King George V with six or eight 15-inch weapons,[18] because attention turned to the concerns created by the ‘escalator’ clause allowing 16-inch guns.[19]

This clause referred only to main armament.[20] It did not automatically increase maximum battleship displacement to 45,000 tons, as sometimes stated in even authoritative works.[21] As a result, the remaining signatories focused during 1937 on developing on 16-inch gunned, 35,000 ton fast battleships with adequate immunity zones against their own main armament. This was challenging. The British had been looking into this while the King George V class were under development,[22] as had US designers.[23] Based on work done to develop the King George V,[24] the Admiralty initially believed such a ship, with the characteristics they required, could not be built to 35,000 tons.[25] But, as we saw in the previous article, 1937-38 studies by the Constructor’s department showed that such a ship was – just – possible in those terms with certain compromises.[26] And as we also saw, similar US thinking led to the South Dakota class,[27] although their other specifications differed from the British.[28]

In the event, however, the British did not build their South Dakota equivalent, design ‘16B/38’,[29] or its near-variants, described in the last article. These were overtaken by a revision of the agreed treaty displacement. In many respects this was inevitable.[30] Warship capability was defined by more than guns, speed and armour. It included range, habitability, sea-keeping, stability, underwater defence and a multitude of other factors; and at 35,000 tons the battleship mix had to compromise.[31] One concern was Japan’s ability to build ships unrestricted by treaty – which Japanese diplomats implied could mean 40,000 tons,[32] although both the US and Britain believed Japan’s new ships would be at least 43,000.[33] There was also the fact that the US Navy were concerned by the design speed of the South Dakotas, which now seemed insufficient for fleet work.[34] By late 1937 the US Navy was contemplating higher speed battleships for which initial sketches, completed in early 1938, began with a displacement of just over 49,000 tons standard.[35]

The 1936 treaty gave signatories the ‘right to depart’ from its limitations if a power ‘not a party to the present Treaty’ were to build ships exceeding it, providing the signatories could all agree to the departure.[36] Discussions accordingly began between Britain, France and the United States on 31 March 1938 with the intention of raising the displacement limit.[37] United States negotiators were looking for at least 45,000 tons, which caused consternation in the Admiralty because of Britain’s constrained infrastructure and financial position. As the First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Ernle Chatfield,[38] pointed out, any ship with beam over 110 feet – which the combination of Britain’s requirements and 45,000 ton displacement implied – could not be docked in home yards.[39] For this reason the British wanted to keep the limits to around 40,000 tons; but Sir Stanley Goodall, the Director of Naval Construction, thought that, if pushed, they could accept 43,000.[40]

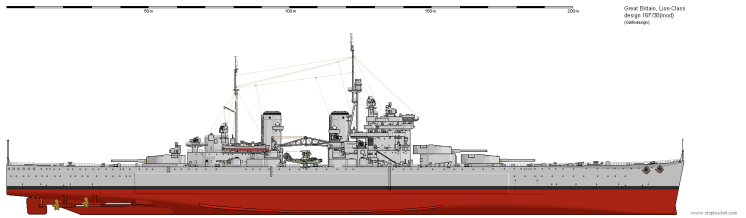

HMS Lion, shown if completed around 1943 to Design 16/F, modified. Garlicdesign, via Shipbucket, Creative Commons CC 4.0 non-commercial license.

These negotiations – with their political and practical constraints from the British perspective – led to a special protocol signed on 30 June 1938,[41] modifying Article 4 and confirming a new treaty displacement of 45,000 tons, to which the US Navy’s high-speed battleships, the Iowa class, were then built.[42] The British had to build closer to 40,000 tons because of their infrastructure limits,[43] but that still gave the Constructor’s department opportunity to develop a more capable 16-inch gun battleship than 16B/38. Work was already under way on possible designs – alphabetically numbered in sequence – while treaty re-negotiation was under way,[44] in part to help inform British negotiators. The final 1938 design was an evolution of the earlier 35,000-ton designs for 16-inch ships, and produced a vessel similar in appearance to King George V but with nine 16-inch guns and a transom stern, on a standard displacement of around 40,550 tons. The first two, Lion and Temeraire, were ordered in February 1939, and laid down mid-year.[45]

The story of Britain’s battleships continues in the next article. Jump across to this article for details of the Iowa class. For more on naval history, check out my book The Battlecruiser New Zealand: a Gift to Empire. Click to buy.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2018

Notes

[1] Norman Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, Seaforth, Barnsley, 2015, p. 336.

[2] Ibid, p. 325.

[3] lan Raven and John Roberts, British Battleships of World War Two: The Development and Technical History of the Royal Navy’s Battleships and Battlecruisers from 1911 to 1946, Arms & Armour Press, London 1976, p. 325.

[4] Naval Limitation Treaty (Second London Naval Treaty) of 25 March 1936, Part 2 Article 4 (2), text at https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000003-0257.pdf

[5] See, e.g. Garzke and Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, p. 173.

[6] See https://www.navygeneralboard.com/the-king-george-v-class-better-battleships-than-history-usually-admits/ for discussion.

[7] Naval Limitation Treaty (Second London Naval Treaty) of 25 March 1936, Part 2 Article 4 (2), text at https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000003-0257.pdf.

[8] Discussed in Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, pp. 324-325.

[9] Garzke and Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II,pp. 176-177.

[10] Ibid, p. 176.

[11] Noted in Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 325.

[12] Two of the mountings were ordered in 1915 for HMS Renown and Repulse when originally ordered as 8-gun battleships, http://battleshiphmsvanguard.homestead.com/15inch.html

[13] http://battleshiphmsvanguard.homestead.com/cathro.html

[14] For brief discussion, see Ian Sturton (ed) Conway’s All The World’s Battleships, Conway Maritime Press, London 1987, pp. 85-86.

[15] For example, http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_15-42_mk1.php

[16] For further discussion see part 2 of this article, and sources.

[17] Norman Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, Seaforth, Barnsley, 2015, p. 336.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid, p. 325.

[20] See Naval Limitation Treaty (Second London Naval Treaty) of 25 March 1936, Part 2 Article 4 (2), see text at https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000003-0257.pdf

[21] Including Robert O Dulin and William H. Garzke, Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II, Macdonald and Janes, London, 1976, p. 107.

[22] Garzke and Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, pp. 170-171.

[23] Dulin and Garzke, Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II pp. 71-72.

[24] Garzke and Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, pp. 170-171.

[25] All tonnages in this article are British ‘long tons’, per definition in the Naval Limitation Treaty (Second London Naval Treaty) of 25 March 1936, Article 1 (a) (3), https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000003-0257.pdf

[26] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 327.

[27] Dulin and Garzke, Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II, pp 71-72.

[28] Garzke and Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, p. 230.

[29] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 327.

[30] See, e.g. R. E. J Galilee, ‘The Breakdown of Naval Limitation in the Far East – 1932-36’, MA Thesis, University of Canterbury, 1975.

[31] Other specifications and limitations included, but were not limited to, unrefuelled range, blast interference from armament, habitability for crews, performance after certain times out of dock, and loadings after modifications.

[32] Noted in Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-36, p. 329.

[33] William H. McBride Technological Change and the United States Navy, 1865-1945, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2010 (paperback), p. 25. This was a radical underestimate; the Yamato class displaced more than 69,000 tons standard.

[34] Dulin and Garzke, Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II, p. 110.

[35] Dulin and Garzke, Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II, pp 108-109.

[36] Naval Limitation Treaty (Second London Naval Treaty) of 25 March 1936, Article 25 (1), (2) and (3) at https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000003-0257.pdf

[37] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-36, p. 329.

[38] Beatty’s flag-captain at Jutland.

[39] See, e.g. Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-36, p. 329.

[40] Ibid.

[41] See ‘Limitation of Naval Armament: protocol signed at London, June 30 1938, modifying treaty of March 25, 1936’, https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000003-0523.pdf

[42] Dulin and Garzke, Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II, pp 112-115.

[43] Friedman, The British Battleship 1906-46, p. 329.

[44] Ibid.

[45] July and June respectively, see Garzke and Dulin, British, Soviet, French and Dutch battleships of World War II, p. 263.

Recent Comments