On the afternoon of 31 May 1916, and on into the early hours of 1 June, the British Grand Fleet and the German fleet came to blows off the Denmark coast in a battle known to the British as the Battle of Jutland, to the Germans as the Skagerrak.[1]

It was the first – and last – great confrontation between the immense dreadnought battle fleets built at such colossal expense during the years leading up to the First World War. And it left thousands dead, many killed as they went down with ships that sank in minutes after devastating magazine explosions.[2]

HMS Iron Duke opens fire at Jutland. Painting by Lionel Whyllie, public domain.

Afterwards the argument raged: who won? It was pursued at the time through the press and through public debate – in which the reputes and good names of the admirals involved were bandied about.[3] The scandal became heated in the 1920s, particularly in Britain, where even the official history of the day has been shown to be partisan.[4] We will look at the scandal in the second part of the article.

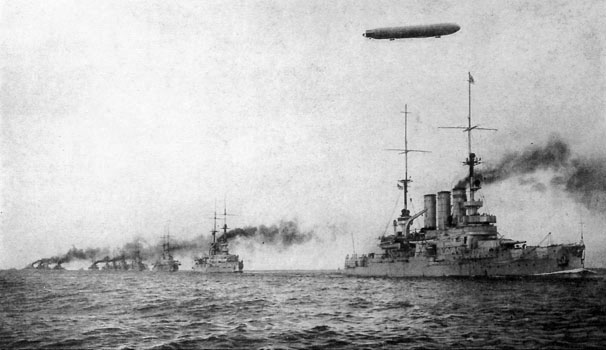

HMS Orion during the First World War. Public Domain, via Wikipedia.

Recent analysis proposes that the public prestige of the Royal Navy, particularly, never quite recovered.[5] The debate has been pursued since, and often with no less heat, by naval historians and enthusiasts.[6] All this highlights a key point: historically speaking, the question is one of many, naval and otherwise, that cannot be resolved with a single word or sentence. The fact of the Jutland debate continuing over more than a century indicates that the answer, in reality, can only be a discussion, and a quite lengthy one at that.

From this perspective the actual answer to ‘who won’ is ‘it depends how you view things’. The focus of this article is not to debate the battle itself, but to explore some of those viewpoints – for there were several factors and frameworks wrapping the events of the day.

The first and perhaps main issue was expectation, particularly among the British public. The late nineteenth century and early twentieth was the great age of ‘social militarism’ around Britain and Europe, particularly, in which public enthusiasms for all things military were entwined with nationalist fervour.[7] In Britain, which had a long history of naval superiority, the focus was inevitably the Royal Navy where Horatio Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar in 1805 was taken as the pattern for what the navy should do in any new war.

What this drove was an idea that the great dreadnought fleet built from the mid- Edwardian period would immediately sally forth when war broke out and engage the Germans, destroying the German fleet in a swift show-down. The possibility of not having the strength to do this drove the ‘naval panic’ of 1908, when it appeared that Germany might be building more dreadnoughts than expected; and it pushed political thinking to ensure that, at all cost, the British had more.[8] In 1909 this was defined as 60 percent above the next largest power.[9] In 1912, when Winston Churchill became First Lord of the Admiralty, this became a 3:2 ratio relative to Germany – pretty much the 60 percent figure, adjusted to accommodate negotiations with the Germans.[10]

HMS Queen Mary blows up at Jutland, as seen from the German lines. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

To some extent, British naval strategists also bought into this thinking – and certainly, the idea of a fleet engagement could not be ruled out. But in the years leading up to the First World War, thinking was also changing. The idea of blockading Germany by patrolling directly outside their harbours – as the Royal Navy had done to Napoleon a century earlier – was not going to work in an age of mines and torpedoes. By 1914, British policy revolved around a ‘distant blockade’, bottling the Germans up in the North Sea, particularly, by closing its exits.

That flowed in part from the strategic reality – long understood – which was that the navy itself was simply a device for keeping the essential sea lanes open, not an end in itself. It was also the last bulwark against a German invasion. This thinking was not new, although it had been given particular form for the early twentieth century by US naval thinker Alfred Mahan, who updated the ideas for the new industrial age technologies.

The tension between the two ideas – that the Royal Navy could, and should, destroy the German fleet; versus the need to keep it intact to preserve the sea lanes – was what underpinned and drove much of the Jutland controversy after the war. What the British commander, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, did not deliver – and what he was criticised for – was the decisive ‘second Trafalgar’ that the public and even elements within the Admiralty were eager to see.

Worse, the British had – numerically – suffered far heavier losses than the Germans, notably three battlecruisers sunk, versus one German battlecruiser and one old pre-dreadnought battleship. This did not dent British naval superiority, but gave the battle the superficial appearance of defeat. This disparity of loss certainly drove the initial British public response – which was to assume it had been a British defeat, despite everything.[11]

What this masked was the fact that Jellicoe had delivered the key strategic result. On 1 June, his Grand Fleet was in sole possession of the North Sea, and was intact. As a New York journalist put it, the German fleet had ‘assaulted its jailer’ – but they were ‘still in jail’.[12]

HMS Indefatigable sinking, seen from HMS New Zealand. LT CMDR H T DAY – Q 64302, Imperial War Museums (collection no. 3904-01). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HMS_Indefatigable_sinking.jpg#/media/File:HMS_Indefatigable_sinking.jpg

Another of the factors in which debate over Jutland has been wrapped is the conduct of the battle itself – the idea that individual commanders ‘could have’ or ‘should have’ done one thing or another in order to achieve a more decisive result . A good deal of argument has gone into this aspect – whether Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty made mistakes leading his battlecruisers; how Jellicoe fared with the Grand Fleet; and what Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer thought he was doing, steaming twice into heavy British fire. To some extent these debates are tied up in the ‘second Trafalgar’ notion – the idea that Jellicoe, particularly, ‘should have’ achieved more than he did.

From the German perspective there is no question that Scheer aggressively handled his fleet during the war; he had the inferior force, and knew it, but that did not prevent him pursuing a general policy in which he hoped to whittle down the British by destroying isolated squadrons. At Jutland, he came close to achieving it. And yet, when the crunch came, he was tactically out-manoeuvered by Jellicoe – his ‘T’ was crossed not once, but twice. Scheer never adequately explained that second advance.[13] What was he thinking? This demands further debate.

One point often underplayed is the issue of command and control. The fleets were directed by flag signal – unchanged since Nelson’s day – and, occasionally, light and semaphore signalling, the latter a method in which a sailor would stand prominently on a platform, hold a couple of flags, and make stylised arm movements that – in theory – could be read by a telescope in the distance. All this was seriously problematic at the battle ranges of the day, producing several failures, particularly during the early part of the battle when the Fifth Battle Squadron – supporting Beatty’s battlecruisers – missed key signals. How did this affect the battle otherwise?

Into this mix came the fact that visibility was variable and generally poor; commanders on both sides relied on their scouting vessels, and the British – particularly – were notable for variously being cryptic, or failing to report at all. When Jellicoe deployed the Grand Fleet into line from its cruising stations, he had one chance to get it right – but nobody told him exactly where the German fleet was, and he couldn’t see them from the bridge of his flagship, Iron Duke. The fact that he did get it right despite this speaks much for his capability as a commander. Later, when the German fleet barged across the wake of the Grand Fleet at night, nobody told Jellicoe that was happening either, although there were repeated fire-fights between destroyers and dreadnoughts.

The other main framework of the battle which needs substantial consideration was the fact that it was the very first time the great dreadnoughts of the industrial age had come to real blows. There had been only one battlecruiser-to-battlecruiser fight before, at Dogger Bank in January 1915.[14] And this was the issue. In Nelson’s day, around the turn of the nineteenth century, commanders could draw on more than a century’s experience of fighting cannon-armed, wooden-walled sailing ships. They knew exactly what the technology could do and how to work it.

But the advent of industrial technology re-set the dice, and re-set it more than once. By 1916 a good deal of theoretical work had been done, and a few lessons were learned during the initial engagements. But even at Jutland, nobody knew how the ships would actually perform. The lessons learned from the battle affected everything from shell-proofing systems to armour attachment methods and – most significantly – munitions storage and handling procedures.

This last factor explains one thing about the British tactical performance. Sir John Jellicoe had made a special study of the engineering of his ships – had, indeed, been part of the original design committee that developed HMS Dreadnought in 1905. He was well aware of the theoretical capabilities and the practical unknowns. When coupled with the strategic need to maintain British superiority, come what may, he was probably right to be cautious when handling the Grand Fleet.

All of these issues, of course, are discussion points. We will pick up the story of the ‘Jutland scandal’ in the second part of this article.

For more on naval history, check out my book The Battlecruiser New Zealand: a Gift to Empire. Click to buy.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2018

Notes

[1] This reflected naming conventions: the Germans drew distinction between the waterway (Skagerrak) and the nearby coast (Jutland), see Reinhard Scheer, Germany’s High Seas Fleet in the World War, Cassell, London 1920 p. 136.

[2] For casualty lists see http://www.naval-history.net/xDKCas1916-05May-Jutland2.htm, accessed 26 May 2018.

[3] For example, Reginald Bacon, The Jutland Scandal, Hutchison, London 1925; Winston S. Churchill, The World Crisis, Four Square, 1960 (reprint), pp 676-724

[4] Andrew Lambert ‘Writing the battle: Jutland in Sir Julian Corbett’s Naval Operations’, The Mariner’s Mirror, Vol. 103, No. 2, May 2016, pp. 175-195, also at, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00253359.2017.1304698?src=recsyshttps://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00253359.2017.1304700?journalCode=rmir20, accessed 26 May 2018.

[5] Eric Grove, ‘The Jutland paradox: a keynote address’, The Mariner’s Mirror, Vol. 103, No. 2, May 2017, pp. 168-174, also at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00253359.2017.1304698?src=recsys, accessed 26 May 2018.

[6] Virtually every book on Jutland discusses it, e.g. Captain Donald Macintyre, Jutland, Evans Brothers, London 1957, pp. 186-195; Nigel Steel and Peter Hart, Jutland 1916: death in the grey wastes, Cassell, London pp 417-435, etc.

[7] See, e.g. Matthew Wright, Shattered Glory, Penguin, Auckland 2010, pp. 29-32.

[8] For analysis of the period see Jon Tetsuro Sumida, In Defence of Naval Supremacy: Finance, Technology and British Naval Policy 1889-1914, Routledge, London 1993.

[9] Lawrence Sondhaus, Naval Warfare, 1815-1914, Routledge, London 2001, p. 203.

[10] Ibid, but see also Peter Padfield, The Great Naval Race: Anglo-German Naval Rivalry 1900-1914, Hard-Davis MacGibbon, London, 974, pp. 282-283.

[11] See, among others, e.g. Roger Parkingon, Dreadnought: the ship that changed the world, I.B. Tauris, London 2015, P. 235.

[12] Widely quoted even in general histories, e.g Thomas William Heyck, A History of the Peoples of the British Isles from 1870 to the present, Routledge, London 2002, p. 114.

[13] Scheer, p. 155.

[14] Churchill, p. 380, noted explicitly it was the very first such battle in history.

Recent Comments